Candyfloss (8 page)

Authors: Nick Sharratt

‘I want you to have this, Floss,’ said Mum, handing me an envelope. ‘It’s an open airline ticket to Sydney. You can use it any time in the next six months. It’ll be strange travelling such a long way on your own, but the stewardess will look after you. Or of course you can change your mind now and come with us after all.’

I wanted to cling to Mum and say

Yes yes yes!

But I saw Dad’s face. He was nodding and trying to smile. I

couldn’t

say yes. I just shook my head sadly, but promised I’d take great care of the ticket.

Dad opened the van door. Steve lifted me in. Mum gave me one last kiss. Then we were driving away from my mum, my home, my whole family . . .

I waved and waved and waved long after we’d turned the corner and were out of sight. Then I hunched down in my seat, my hands over my mouth to stop any sound coming out.

‘It’s OK to cry, darling. Cry as much as you want,’ said Dad. ‘I know it must be so awful for you. You’re going to miss your mum so.

I’ll

miss her, in spite of everything. But she’ll be coming back in six months, and the time will simply whizz by. If I can only win the lottery we’ll both jet out to Sydney for a month’s holiday, just like that. Yeah, if I could win the lottery

all

our problems would be solved.’ Dad sighed heavily. ‘I feel so bad, little Floss. I should have insisted you go with your mum.’

‘I want to be with you, Dad,’ I murmured, though I wasn’t sure it was true now.

We went back to the café. Dad opened it up and got the tea and coffee brewing. There wasn’t much point. We had no customers at all, not even Billy the Chip or Old Ron or Miss Davis.

‘I might as well shut it up again. I doubt anyone will be in until lunch time, if then,’ said Dad. ‘Come on, kiddo, let’s go out for a bit. What would you like to do?’

That was the trouble. I didn’t really want to do

anything

. We mooched around the town for a bit, peering in some of the shops. There wasn’t much point getting excited about anything because I knew Dad didn’t have any money. He tried to start up this game of what we’d buy if we won the lottery. I didn’t feel like joining in much.

‘I suppose your mum’s Steve could buy you any of this stuff with a flash of his credit card,’ Dad said.

‘I don’t want any of it,’ I said.

‘That’s my girl. The simple things in life are best, eh?’ Dad said eagerly. ‘Come on, let’s go to the park and feed the ducks. You like that, don’t you?’

I wondered if I was getting too old for feeding the ducks, but we picked up a bag of stale sliced bread back at the café and trundled down to the park, even though it had started raining.

‘It’s only a spot of drizzle,’ said Dad.

By the time we reached the duckpond we were both wet through and shivering because we hadn’t bothered with our proper coats.

‘Still, nice weather for the ducks,’ said Dad.

They were swimming round in circles, quacking away. Mother ducks and ducklings.

I threw them some bread, large chunks for the mothers and dainty bite-sized morsels for the ducklings, but they seemed full to bursting already. There were large chunks of bread bobbing all around them but they couldn’t be bothered to open their beaks. They’d already had so many visitors. Mothers and toddlers.

‘Never mind, let’s take the bread back home and make chip butties, eh?’ said Dad. ‘Two for you and two for me. Yum yum in the tum!’

I wasn’t listening properly. I was looking up at an aeroplane flying high in the sky, as small as a silver bird.

‘Your mum won’t be on her plane yet,’ Dad said softly. ‘They aren’t going to the airport till this evening. It’s a night flight.’

I had mad thoughts about packing my case, running like crazy to Mum’s and begging her to take me after all.

Maybe that was why I was so fidgety when I got home. I heaved around on the sofa, I lolled about the floor, I watched ten minutes of one video, five of another, I read two pages of my book, I got out my felt pens and started a drawing and then crumpled up the paper. I ended up rolling the pens all over the floor, flicking them moodily from one side of the room to the other.

One went right under the sofa. I had to scrabble for it with my fingers. I found little balls of fluff, some old crisps, a tissue and a screwed-up letter. I opened it up and saw the word

debt

and the word

court

and the word

bailiffs

before Dad snatched it away.

‘Hey, hey, that’s

my

letter, Floss,’ he said. He crumpled it up again, screwing it tighter and tighter in his hand until it was like a hard little bullet.

‘What is it, Dad?’

‘Nothing,’ said Dad.

‘But I thought it said . . .?’

‘It was just a silly letter sent to try to scare me. It’s not going to, OK?’ said Dad. ‘Now, you just forget all about it, there’s a good girl. Come on, let’s have our chip butties!’

Dad made two each, and one for luck. I could only eat half of one, and that was a great big effort. It turned out Dad didn’t have much appetite either. We looked at the chip butties left on the plate. It was as if Dad had made enough for both my families. I wasn’t sure I could stand to be in this very small family of two now. I wasn’t sure how we were going to manage

.

8

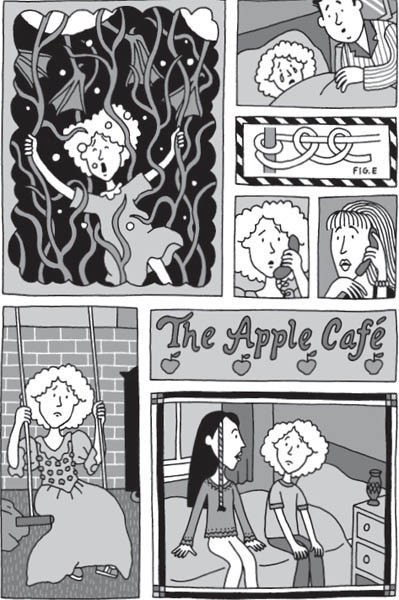

I WAS SWIMMING

in an enormous duckpond, gigantic birds with beaks as big as bayonets swooping towards me. I opened my mouth to scream for help and started choking in the murky green water. I coughed and coughed and went under. I got tangled in long slimy ropes of weed. I couldn’t struggle free. The vast ducks swam above my head, their great webbed feet batting me. I was trapped down there, my lungs bursting. No one knew, no one cared, no one came to rescue me . . .

I woke up gasping, soaked through. I thought for one terrible moment I might have wet myself – but it was only a night sweat. I staggered up out of my damp bed, mumbling, ‘Mum, Mum’ – and then I remembered.

I stopped, shivering on the dark landing. I couldn’t run to Mum for a cuddle. She was six miles up in the air, halfway across the world.

I started crying like a baby, huddled down on the carpet.

‘Floss?’

Dad came stumbling out of his bedroom in his pyjamas and very nearly tripped over me. ‘What are you doing

here

, pet? Don’t cry. Come on, I’ll take you back to bed. It’s all right, Dad’s here. You’ve just had a bad dream.’

It seemed as if I was stuck in the bad dream. Dad tucked me in gently but he didn’t know how to plump up my pillow properly and smooth my sheet. He didn’t find me a big tissue for my runny nose. He didn’t comb my hair with his fingers. He did kiss me softly on the cheek, but his face was scratchy with stubble and he didn’t smell sweet and powdery like Mum.

I tried to cuddle down under the duvet but it smelled wrong too, of old house and chip fat. I wanted to go to

Mum’s

house, but it was all changed. Our stuff was all packed up. Soon there would be strangers renting it. I imagined another girl my age in my white bedroom with the cherry-red carpet and the cherries on the curtains. I saw her looking out of my window at my garden and my special swing and I couldn’t bear it.

Three months ago Steve had fixed up the baby swing for Tiger, all colours and bobbles and flashing lights. I’d done the big sister bit and patiently

pushed

him backwards and forwards, but I couldn’t help remarking that I wished

I’d

had a swing when I was little.

I didn’t think Mum and Steve had taken much notice, but the next weekend when I was at Dad’s Steve rigged up this amazing proper traditional wooden swing, big enough for an adult – certainly big enough for

me

.

‘My swing!’ I sobbed now.

‘What? Please don’t cry so, Floss, I can’t make out what you’re saying,’ said Dad, sounding really worried. ‘Listen, I know how badly you’re missing your mum. I’ve got your airline ticket safe in the kitchen drawer. We can book you onto a flight and you can join up with them. It will be like a big adventure flying all that way.’

‘No, no. I want my

swing

,’ I said.

Dad missed a beat before he understood. ‘Well, that’s easy-peasy,’ he said. ‘We’ll nip round to your mum’s place tomorrow and take your swing. Don’t upset yourself, darling. Your old dad will sort things for you.’

We went round to the house early Sunday morning, before Dad opened up the café. Dad parked the van outside the house. It looked so absolutely normal I couldn’t believe Mum and Steve and Tiger weren’t lurking behind Mum’s ruched blinds.

We didn’t have a key, but we didn’t need one to wiggle open the bolt of the side gate and walk round into the back garden. Tiger’s swing wasn’t there. It had been dismantled and packed up. The only trace of it was the four square marks in the grass where the legs had been.

My

swing still stood there sturdily. Too sturdily. Dad tried and tried to take it down. He even broke into the garden shed and bashed at the swing’s supports with Steve’s tools. The swing didn’t budge but Steve’s stainless-steel spade got horribly dented.

‘Oh bum,’ said Dad. ‘Now I suppose I’ll have to pay for a new blooming spade on top of everything else.’

‘Never mind, Dad.’

‘But I

do

mind. Why am I so useless? Look, I’m going to collapse that swing if it’s the last thing I do.’

Dad battered and bashed a lot more. He tugged and tussled with the swing. He even tried digging around it with the bent spade, but the supports went way way down – almost to Australia.

Dad stood still, wiping his brow, his face damp and scarlet.

‘It doesn’t matter, Dad, honestly,’ I said.

‘It matters to me,’ said Dad grimly.

I peered up at the swing, wishing I hadn’t said

a

word. Dad stared too, his brow furrowed, as if he was trying to fell the swing by sheer willpower. Then he suddenly clapped his hands and ran and got Steve’s scary long pruning shears.

‘Dad! What are you going to do?’

‘It’s OK, Floss. I’ve just worked it out. We’ll liberate your swing. We just need the rope and the seat. We don’t

need

the stupid supports. It’s going to be a

portable

swing now, you’ll see.’

Dad reached up and snipped at the top of each rope. They came thumping down with the wooden seat attached. ‘There!’ he said, as if he’d perfected the most astonishing trick.

I blinked doubtfully at the severed swing and said nothing.

When we got back home Dad took the swing out in the back yard. He’s never actually got round to turning it into a proper garden. There’s not really room, anyway. There are big wheelie bins for taking the rubbish from the café, and all the cardboard boxes of old stuff that Dad’s going to sort one day lurking under tarpaulin, and bits and pieces of very old bikes, and an electric scooter that never worked properly.

There’s a tiny flowerbed of pansies because Dad says they’ve got smiley faces, and an old sandpit I used to play Beaches in when I was very little, and an ancient gnarled apple tree that’s too old to

produce

any fruit, although it was the reason Dad bought the café long ago. He was going to make our own apple pies and apple cake and apple chutney and apple sauce. He painted a big new sign to go above the door –

THE APPLE CAFÉ

– and he painted the walls and windowpanes bright apple-green.

He changed the name to Charlie’s Café long ago, but the apple-green paint’s still there, though it’s faded to a yellowy-lime and it’s peeling everywhere. Mum always nagged Dad to chop the apple tree down because it wasn’t doing anything useful, just causing shadows in the yard, but Dad reacted as if Mum had asked him to chop

me

down.

‘We’ll hang your swing on the apple tree!’ Dad said now.

He spent all afternoon putting it up. He tested the branches first, swinging on them himself, yelling like Tarzan to make me laugh. I still didn’t feel a bit like laughing but I giggled politely.

Then Dad went up and down a ladder, fixing one end of the swing rope here and the other end there. He had to take an hour’s break hunting down an ancient encyclopaedia in a box of books in the attic to find out how to do the safest knots.

When at last he had the swing hanging we found it was too low, so that my bottom nearly bumped the ground. Dad had to start all over again,

shortening

the ropes. But

eventually

, late afternoon, the swing was ready.

‘There you are, Princess! Your throne awaits,’ Dad said, ultra proudly.

I put on my birthday princess gown over my jeans to please him and sat on my swing. Dad beamed at me and then went pottering off again to find his old camera to commemorate the moment. He didn’t come back for a long time.

I had to stay swinging. I didn’t

feel

like swinging somehow. I wouldn’t have told Dad for the world, but you couldn’t really swing properly now it was attached to the apple tree. The swing juddered about too abruptly and hung slightly lopsided, so you started to feel queasy very quickly. It wasn’t very pretty out in the back yard staring at the tarpaulins and bits of bikes, and the wheelie bins were very smelly.