Cannonbridge (33 page)

Toby grins still more widely. “Oh, but you lived too long in the nineteenth century, Mr Cannonbridge. This is the twenty-first. And we do things differently here.”

With a snarl, the monster lunges again. “What have you done, you ridiculous little man?”

“I’ve tweeted a link to my final chapter.”

Cannonbridge looks as though he may very well be about to vomit. “Explain your actions. Immediately.”

“I hacked old Salazar’s account. @cannonbridgedon. Turns out his password is my wife’s maiden name. And I’ve tweeted that link. He has five million followers. Even now it’ll be going viral. It’ll be all over the internet. Retweeted, Facebooked, reported, reposted. Everywhere. And very soon, Mr Cannonbridge, the world will think that you were torn apart, reduced to nothing by the river. No hiding in its inky depths. No growing strong on all that belief. Just an illusion dispelled.”

And then, with a savage roar, battle begins in earnest—combat in which Toby is easily outmatched, unable even to parry the majority of the blows but knowing all the same that he need only survive a little longer before the seed that he has planted in the past bears its strange fruit. Eventually, he simply accepts the beating—the Victorian creature cursing and tearing at him—before the inevitable begins.

Matthew Cannonbridge starts to grow faint, the colour draining out of him, his very reality seeping away.

Toby breaks free, stands and watches and bear witness. He is flickering now, flickering out of existence, guttering like a candle in a winter’s breeze.

And as he stares up at his tormentor, wickedness burning in his eyes, these are the last words of Matthew Cannonbridge.

“I’ve seen this world of yours. And I know who rules it. Men like your Prime Minister are as so many pretty puppets. True power no longer lies in the hands of individual states. You know in this century who possesses it. You know who holds the strings and makes the little people dance. And you think I am alone? All these mighty firms, these intercontinental conglomerates, these planet-straddling banks. They are the new Empire. They control every single aspect of your lives. And what has happened to me will, as inevitable as was the rise of

Homo sapiens

, happen also unto them.”

He is faint now, almost gone, his voice sepulchral and ragged. “I am the first. But you may be assured, Dr Judd, of this. Others are coming. They are on their way. Indeed, think on this, sir—they may already be here.”

A final glance of deathless hatred, a final shudder and, at long last, the saturnine man has gone from the world.

Perhaps unexpectedly, Toby Judd feels a pang of loss, as though something precious has gone out of his life.

But things will be better now, he thinks. Calmer, at least. And the darkness seems less oppressive, less threatening than before.

In fact, wasn’t that a light?

Yes, a strong torch bobbing at speed towards him. Toby doesn’t shout out. He only waits. Soon the torch and its bearer are almost upon him.

A familiar male voice calls out. “Toby?”

Judd smiles. “Here,” he says.

The other man is with him now. “There you are,” says former Corporal Nick Gillingham. There is a smell of musky male sweat, masked insufficiently by a sickly deodorant. “I was starting to get worried.”

“Oh, there’s nothing to worry about,” says Toby, feeling suddenly very tired. “Not any more. What are you doing here anyway?”

“Gabriela sent me. She sent me to bring you home.”

“I see.”

“Not that I wanted to come to this place ever again. But she talked me into it. You know how persuasive she can be.”

Toby smiles. “Yes. I do.”

“Actually, in that department, mate, it must be your lucky day.”

“What on earth makes you say that?”

“Gabriela. I think she really likes you.”

TWO YEARS FROM NOW

I

N THE YEAR

that has passed since the violent dissipation of the creature which had gone by the name of Matthew Cannonbridge, the life of Toby Judd has, slowly yet steadily, become characterised by a state of pure and unprecedented happiness, like a basin being filled to the brim with cool, fresh water.

Today, Toby considers himself to be amongst the most fortunate of men and in the very top percentile of the population when it comes to matters of contentment and joy. He has become, he reckons, one of the lucky ones. He is, though once he might have chuckled cynically at the word, blessed.

He is thinking these thoughts whilst standing in the marble bathroom of a beautiful, though surprisingly reasonably priced, hotel in Paris, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, nestled picturesquely in the shadow of the cathedral. He is here on holiday with his girlfriend, a mini-break away to celebrate both their first anniversary and the completion of Judd’s new book—something of a polemic, perhaps, but written with a good deal of flair and peppered with dry wit, about the dangers of globalisation and the misuse of corporate power. His wilder, occult theories he has kept to himself and chosen not to commit to print for the world, by and large, seems, when it comes to Cannonbridge, to have acquired that convenient amnesia which often arrives in the wake of inexplicable tragedy.

Toby’s rewriting of the past, augmented by the Faircairn dust, seems also to have erased much public awareness of those times, the truth of what happened papered over by an alternative and sanitised version of events, the facts, as Judd remembers them, now only very occasionally glimpsed, faintly visible, as in the first words in a palimpsest.

His ablutions done with, he runs a hand through his hair, splashes on some aftershave, grins and, as satisfied with his appearance as he shall ever be, saunters back into the hotel bedroom in which he knows, with pride and daily gratitude, that a beautiful woman is waiting for him.

As soon as he returns, however, he knows that something is wrong. He understands instinctively that this is not to be an evening like any other. Whatever it is will prove to be more than merely inconvenient or disappointing—it is gravely and permanently

wrong

.

Gabriela is sitting on the edge of the bed, wearing a dark green dress that he had bought her for her birthday, all made up and ready to go out (for their table is reserved in less than half an hour’s time) and looking, in Toby’s opinion, simply more gorgeous than ever.

Yet she is also weeping. Her head is in her hands and her body is convulsed by sobs.

“Darling?” Toby approaches her. “What on earth’s the matter?”

She lowers her hands and looks up, deep sorrow in her eyes. “I’m sorry,” she says.

“Why? Darling, whatever for?”

She sounds utterly resigned. “I think it’s going to be tonight. I’d really hoped that we’d have our anniversary at least... But, no, it seems we shan’t be permitted even that.”

She winces. Her eyes are watering at least as much in pain as from grief.

“Sweetheart. You’re not making any sense. What on earth is the matter?”

Gabriela stands up and wipes her eyes. “Oh, baby,” she breathes. “Haven’t you worked it out yet?” And she takes him tenderly in her arms. “Come on.” She is prompting him gently. “It’s never really made much sense has it? I mean, look at me.”

“You look great, darling. Even with the tears.”

She manages a small, defiant smile but the tone of her voice is unchanged. “You know in your heart, I think. And I suspect you have done for a long time now.”

“I swear that I haven’t.”

“Have you never thought then... how vague I seem? How, I don’t know how best to describe it, how... out of focus?”

“Gabriela, please...”

“I mean, my background seems so shaky, doesn’t it? Thin. Unconvincing. An ex-army sergeant turned Edinburgh waitress with a deep interest in literature. It’s... oh, I don’t know, just too convenient. Don’t you think? And as for my motivation. Why did I ever do what I did? Taking you in, helping you fight, seeing you safely to the island and breaking you out of the nuthatch? What was there, apart from some hazy desire to do good?”

“Darling, I hope you don’t mind my asking but have you had a drink already? You know there’ll be champagne at the restaurant, don’t you?”

“Stop it, my love. Please. You must accept the truth of it. Just hold me now.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Yes, you do, Toby. You do. Have I never reminded you of anyone?”

“Models, pop stars, the crushes of my youth...”

“How about Matthew Cannonbridge?”

“Oh, for God’s sake. Please. Don’t be ridiculous.”

“No. Not as he became. Not the devil-god. But as he was in the beginning. Back in Geneva and in Norwich and with Maria Monk, he was a kind of itinerant philanthropist, wasn’t he? That’s what you’ve always said. He was just a blank space waiting for his true purpose.”

“Hardly,” Toby begins before, with a great convulsive rising in his chest, the physical manifestation of delayed mental acceptance, he stops short. All that he manages is a feeble echo: “Hardly.”

“I just appeared in your life, didn’t I, my darling? And vanished just as quickly. I was only there when you needed me. And there have always been... ellipses in my existence. Didn’t Mr Keen tell you that nothing human could have survived our fight? Well...” She pauses, lets the implication hang in the air.

Toby is crying now too. He does not speak. He only holds her more tightly still.

Although it had been hitherto a quiet, pleasant evening outside, the wind has begun to rattle the windowpane and, as in some old ghost story, the room seems to have become darker, the air to grow soupy and close.

“It’s on its way,” breathes the woman who is not quite a woman. “I can sense it. At this very moment, a small start-up firm is being founded in Tokyo. Within forty years it will be one of the most powerful and voracious brands on the planet. It will possess comprehensive data about eighty percent of the world’s population. You will all be shackled. Their control will be practically invisible and all but absolute.” She gasps for breath, in sudden, vital pain.

“My love? Oh, my love?”

Gabriela jack-knifes, staggers back from Toby as if she has been struck and collapses, winded, upon the bed.

“Stay calm,” Toby says. “There must... There must be something I can do.”

“Nothing.” Her body is wracked by waves of pain. She is contorted. She is twisted up. “Nothing left now,” she says as the wind rattles the glass harder and the lights go out. “My brave darling. Nothing left for you to do but only bear witness.”

And Toby is on his knees and he is taking her hand in his and he is weeping and he is sobbing at this grotesque injustice, at this hideous robbery.

“Gabriela,” he says, too late. “I love you so much.”

No reply. Her hand clenches twice in his.

The room seems battered, besieged by some imperceptible storm.

An awful moan escapes her—almost a shriek—as of some small animal murdered without mercy in the night.

Then the tempest abates, the light returns and the thing on the bed which wears the woman’s skin, sits, with horrible vigour, upright.

“Oh, but I know that,” it says in the voice of Gabriela. “Happy anniversary, Dr Judd.”

And it smiles its inhuman smile.

The author would like to thank:

Jon Oliver and all at Solaris

Robert Dinsdale

Dr David Rogers, Dr Paul Perry and colleagues at Kingston University

Nick Briggs and all at Big Finish Productions

Professor John Sutherland, whose book Lives of the Novelists partially inspired this novel

Michael and Ben for their unflagging and good-humoured support

Emma – the unexpected girl

My parents and my brother, with all my gratitude and love

The ghosts that haunt us are not always strangers...

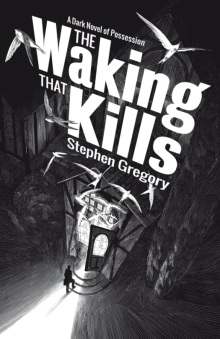

When his elderly father suffers a stroke, Christopher Beal returns to England.

He has no home, no other family. Adrift, he answers an advert for a live-in tutor for a teenage boy. The boy is Lawrence Lundy, who carries with him the spirit of his father, a military pilot – missing, presumed dead. Unable to accept that his father is gone, Lawrence keeps his presence alive, in the big old house, in the overgrown garden. His mother, Juliet, keeps the boy at home, away from the world; and in the suffocating heat of a long summer, she too is infected by the madness of her son.

Christopher becomes entangled in the strange household, enmeshed in the oddness of the boy and his fragile mother. Only by forcing the boy to release the spirit of his father can he find any escape from the haunting.

‘A first class terror story with a relentless focus that would have made Edgar Allan Poe proud’

New York Times on

The Cormorant

‘Gregory’s voice and vision are wholly original’

Ramsey Campbell

‘Intelligent and well-written’

Iain Banks on

The Cormorant