Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (17 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

8.99Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Perhaps owing to his own youthful run-in with the Paris police in 1968, Vieira de Mello had never warmed to law enforcement officials as he had to soldiers. But in Cambodia he understood that, in order for refugees to feel secure once they returned to Cambodia, policing would have to be a vital component of the UN mission. But he also knew that in its forty-seven-year history the UN had never really done policing. Unsurprisingly, almost none of the expected 3,600 police arrived in time for the first refugee returns on March 30, and only 800 would arrive before May. Many lacked driver’s licenses and spoke neither English nor French, UNTAC’s two official languages.

27

27

As hard as it was to quickly rally soldiers to participate in peacekeeping missions, soldiers were at least always on standby in their countries and rarely engaged in actual combat. Police officers, by contrast, tended to be busy doing police work at home and thus could rarely be spared. Police work also relied upon the officers’ links with the local population, and it would be hard to find trained police who had the necessary language skills, the knowledge of local law, and the confidence of the population. The “policing gap” would undermine this and every one of Vieira de Mello’s subsequent UN missions.

Nonetheless, despite the mounting violence and the thinness of UN security forces, he stuck to his plan to go ahead and begin helping refugees return on March 30. He understood the gamble he was taking: If a returning refugee was murdered or stepped on a mine, it would send a chill through the refugee camps in Thailand and possibly torpedo the repatriation operation. This, in turn, could ruin the chances of holding elections the following year. Still, he opposed delaying the launch because he thought it would send a signal to both the spoilers and the refugees that the UN could be cowed. His deputy Fouinat asked Thomson, the public health specialist, “Doc, can you assure us that there will be no deaths in the first convoys?” Thomson was incredulous. “Listen, François, I’m not Jesus Christ,” he said. “People die no matter where they live. People die in Paris.They aren’t going to start not dying just because they are put on UNHCR convoys.”

On March 30 Vieira de Mello traveled to Site 2, the largest camp on the Thai border, and spoke to the 527 refugees who had volunteered to be part of the first returning group. Looking out at men and women who were clinging to their blue departure passes and green nylon UN travel bags containing noodles, sugar, soap, and a toothbrush, he said that the UN had no intention of telling Cambodians—“an independent and proud people”—what to do. The organization would try to create conditions that would enable them “to regain control of their fate and to shape their own future.” “Today, we are, at long last, gathered to make a dream come true: that of breaking the spiral of violence in Cambodia and of witnessing the emergence of a reunited, reconciled and pacified society,” he said. “We are betting on peace. We will, as from this morning and with deep emotion, escort you home.”

28

28

A small contingent of Malaysian peacekeepers would escort the first seventy families who bravely volunteered to return to Cambodia. Beneath signs that read GRATITUDE TO THAILAND in Khmer, Thai, and English, some of the departing refugees wept with fear or anticipation, others smiled and waved, and most filed stoically onto the buses. None had any idea what lay in store for them in their homeland or whether the shaky peace would last.

In his send-off speech Vieira de Mello had sounded more confident than he felt. He had many outstanding questions that only time would answer: Would those who had survived the war inside Cambodia welcome the exiles back? Would Hun Sen’s government treat the refugees as traitors? If they moved in with their extended families, how long would the generosity of their relatives last? Would the returnees’ desperation to return to land they owned before the war lead them to ignore land-mine warnings? Would they give up on rural areas altogether and pour into the cities?

Before the convoy departed Site 2, Vieira de Mello briefly dropped out of sight. He made a short pilgrimage to a shrine in front of the Hotel Sarin, where in front of a three-foot-high statue of the Buddha he burned incense and lit candles, issuing a prayer to the gods—again born more of superstition than faith—that nothing would go wrong.

A firm asphalt road dotted with houses and well-groomed gardens ran from the Thai refugee camp to the border. But once the UN convoy crossed the narrow bridge that marked the crossing into Cambodia, the terrain changed. Sturdy houses gave way to bamboo and leaf shacks, and water wells and pipes were replaced by shallow pools of stagnant water. Abandoned military posts offered reminders of the fighting that had recently raged in the area. In the weeks leading up to the return, some 428 mines had been removed from the road between the border and the UNHCR reception center in Sisophon. The refugees had been warned that just six feet on either side of the road had been cleared, but beyond that mines were omnipresent. In March alone thirteen Cambodian villagers had been killed or maimed by mines in the nearby fields.

29

29

Vieira de Mello traveled in the second vehicle in a refugee convoy of several dozen buses. He maintained radio contact with Dahrendorf of UNHCR, who drove in the lead vehicle. He was so tense that she could hardly recognize his voice. The convoy had left later than he had planned, and he was afraid of being tardy to the welcoming reception in Sisophon, which he had scripted minute by minute.“Nici, can you please tell your driver to go faster,” he thundered over the radio. Dahrendorf explained that if they sped up, they would lose the busloads of refugees behind them. He was insistent. “I said, ‘Drive faster,’ ” he snapped. When she again refused, he ordered her to stop the car and leaped out of the passenger seat. “This is ridiculous,” he blared. “My car will drive in front.” He succeeded in spurring on his driver, but as Dahrendorf had warned, his vehicle outpaced the convoy and ended up having to stop to wait for the buses filled with refugees to catch up.

As the buses wended their way into Sisophon, schoolchildren lined the road waving Cambodian flags, pop music blared, and Cambodian musicians performed traditional song. After a two-hour drive, the refugees disembarked, looking dazed. Some had never set foot outside a refugee camp. In conversations with journalists, they explained their fears. “I’m worried about the Khmer Rouge because they haven’t settled down yet,” said So Koemsan, twenty-eight, whose parents and four siblings had died of starvation during the Maoists’ bloody reign. “If they fail in their objectives, they might take it out on people like us . . . but I hope the UN will protect us.”

30

Eng Peo, thirty-seven, had raised two children in the camp. “I have not been a farmer for many years, and my children have never seen a farm,” he said. “How do I start again?”

31

30

Eng Peo, thirty-seven, had raised two children in the camp. “I have not been a farmer for many years, and my children have never seen a farm,” he said. “How do I start again?”

31

Vieira de Mello had a keen eye for symbolism. He had invited UN blue helmets to intersperse themselves in the convoy so that the peacekeepers would begin to feel ownership over the repatriation operation. But just before he left Thailand—a country that had often treated the Cambodian refugees brutally—the head of the Thai army had told him that he intended to travel to Cambodia to be a part of the welcoming delegation. Throughout the drive Vieira de Mello complained that the general’s very presence would send a paternalistic message from Thailand and would possibly upstage Prince Sihanouk. As his UN car approached the Sisophon reception center, he saw the Thai general standing smugly on the podium with his arms folded. “What the hell does that bastard think he’s doing?” Vieira de Mello fumed to Assadi. “This is not the message we want to send.This is Sihanouk’s show.”

Prince Sihanouk quickly made that clear. He swooped down dramatically in a Russian-made helicopter, along with his wife, Monique, to give the homecoming his blessing, and the Thai general disappeared. As Cambodian officials presented the refugees with orchids onstage,Vieira de Mello spoke into a megaphone, his comments translated into Khmer. “Welcome home,” he said. “We were there for you in Thailand and, I promise you, we will be here to help you resettle in your homeland.”

32

32

Iain Guest, the UNHCR spokesman, watched his boss standing at the dais in the hot sun. Vieira de Mello’s pale blue Asian suit was soaked through with perspiration, and the look on his face was grim, resolute, and triumphant. “For Sergio, that was a moment of fierce vindication,” Guest remembers. “It was a look that said, ‘I told you this would work and by god it did, and I’m going to stand in the sun longer than any of you sons of bitches.’ ”

When asked by a journalist about the recent upsurge in fighting,Vieira de Mello said, “Don’t expect peace to be instantaneous after 20 years of war.The refugees’ return is a strong message to those who are tempted to violate the ceasefire.”

33

But whether the return of refugees would deter the violent—or incite them—remained an open question. And nearly 360,000 Cambodians remained on the Thai-Cambodian border, awaiting UN help.

33

But whether the return of refugees would deter the violent—or incite them—remained an open question. And nearly 360,000 Cambodians remained on the Thai-Cambodian border, awaiting UN help.

Five

“BLACK BOXING”

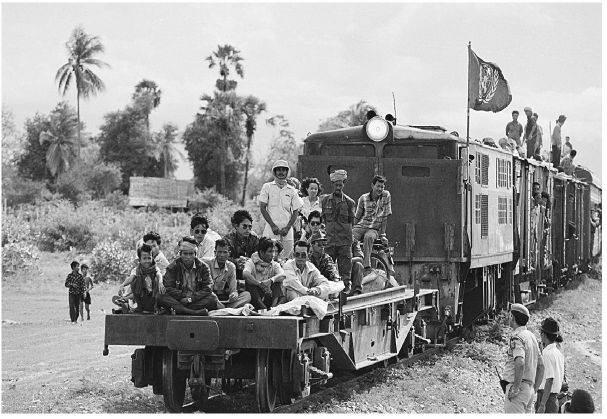

Cambodian refugees returning to their country on the UN-renovated Sisophon Express.

As a student of philosophy Vieira de Mello had often pondered the nature of evil. But in Cambodia he actually got to know some of the world’s most feared mass murderers. Soon after arriving in Phnom Penh, he had visited the Tuol Sleng torture and execution center, where the Khmer Rouge had murdered as many as 20,000 alleged opponents and which Hun Sen’s government kept open as a museum. Although he was thoroughly revolted by the photos of executed men and women of all ages, he was absolutely convinced that he and other UN officials had to engage potential spoilers. He was convinced that peace hinged upon whether the UN could secure the Khmer Rouge’s cooperation. For many humanitarians the prospect of working with the Khmer Rouge was loathsome. Human rights advocates had criticized international mediators for glossing over Khmer Rouge crimes—deliberately avoiding the word “genocide” in the Paris agreement, for instance, and stipulating euphemistically that the signatories wished to avoid a return to “past practices.” But Vieira de Mello believed in what he called “black boxing.” “Sometimes you have to black box past behavior and black box future intentions,” he told colleagues. “You just have to take people at their word in the present.” He returned to Kant’s admonition, “We should act

as if

the thing that perhaps does not exist, does exist.”

1

as if

the thing that perhaps does not exist, does exist.”

1

The Khmer Rouge were bitterly disappointed by UNTAC’s performance. They had expected Akashi and the UN Transitional Authority to take charge of Cambodia and end Vietnamese influence in the country. But while the Paris agreement had authorized the UN to take direct control of the key ministries, a mere 218 UN professionals—95 in Phnom Penh and 123 in the provinces—had been tasked to supervise the activities of some 140,000 Cambodian civil servants in Hun Sen’s government, and almost none of the UN officials spoke Khmer.

2

UNTAC’s role was thus inevitably more advisory than supervisory.

2

UNTAC’s role was thus inevitably more advisory than supervisory.

Akashi had also proven reluctant to exercise the authority and capacity that he had actually been given by the Paris agreement. Although he was supposed to take “appropriate corrective steps” when Cambodian officials misbehaved, he rarely reassigned Cambodian personnel. He told colleagues that because the Japanese constitution had been imposed by Douglas MacArthur and the American occupiers after World War II, it had lacked legitimacy with many Japanese. He believed that the UN would alienate Cambodians if it tried to impose its vision. When the Khmer Rouge saw that Akashi intended to take a minimalist approach to his job, they began to renege on the commitments they had made in Paris. If Hun Sen would not relinquish control of the key ministries or purge the Vietnamese, the Khmer Rouge would in turn deny UNTAC access to its territory. None of the factions that had been at war since the early 1970s agreed to disarm.

Other books

Thread of Betrayal by Jeff Shelby

Carnal Magic: The Wraith Accords, Book 1 by Lila Dubois

No Good For Anyone by Locklyn Marx

Missing Rose (9781101603864) by Ozkan, Serdar

Casanova Killer by Tallulah Grace

Within the Candle's Glow by Karen Campbell Prough

The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature by Geoffrey Miller

Paranoiac by Attikus Absconder

The Stranger You Seek by Amanda Kyle Williams