Chernobyl Strawberries (12 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

I could hardly own up to the fact that I was not having tea with âmy uncle' the general every Thursday afternoon. In a sense we must have been related â as the White Throats all are, in one way or another, since there are no more than a couple of hundred of us extant around the world. As far as Brka was concerned, I clearly hailed from the right side of the tracks.

That quite a few, even perhaps a majority of my wider family, might have been on the other side, or sides (in any war you cared to mention), was not to be looked at too closely.

Whoever was to blame or to credit, I was undeniably among the group of students gathered in the senior common room of our Belgrade

lycée

on a rainy February day, waiting to join the party which would barely survive for another five or six years. I am aware that the quaint French tag of

lycée

hardly does justice to the fifties, Mies van der Rohe-inspired, modernist powerhouse of learning and teenage romance I attended between the ages of fourteen and eighteen. âGrammar school' sounds to me too earnest and plain, almost Quakerish, and âgymnasium' too weird and Germanic for my alma mater, known locally as XIII Beogradska Gimnazija, and situated on the brow of one of the city's leafy hills. Today in Britain it would be called a city academy. It educated some of the most intelligent and most fashion-conscious young people east of the Iron Curtain.

The city of Belgrade and its

lycées

could in fact be divided into three rings. In the inner ring â the

Centar

or the Town, as it was often metonymically referred to â the

lycées

were numbered in single Roman numerals, and were, as a rule, housed in neoclassical, butter- or soot-coloured edifices with roofs supported by muscular stone giants. These had been the boys' and girls' schools of the pre-war Serbian elite. The education system continued to be highly selective, perhaps even more so, under the communists. You could not get a place in a good

lycée

without a solid combination of the right kind of home address, high grades, parental connections and sometimes even expensive weeks of cramming for the entrance exam. (My sister, for example, inherited the same tutor who had put my father through his paces some thirty years before, an out-of-work

pre-war university professor with a whole shelf of books to his name.) At least the schools were now free of charge and co-ed.

The students of the âTown'

lycées

were a weird mixture of the sallow offspring of the newly privileged who occupied the grand apartments hastily abandoned by the old elite in 1941 or 1945, grumpy âold Belgraders' of all persuasions who remained in basement and attic flats, and the bright sons and daughters of the new working class. The last group spoke a multitude of dialects and frequently sported improbable jumpers, knitted in their villages of origin using the wool of sheep with which they were personally acquainted. They lived four to a room in dilapidated tenements around the multitude of courtyards which clustered like honeycomb between the central boulevards. Their parents' names languished on the waiting lists for new apartments in the housing estates which were endlessly sprouting on the outer ring of the city.

The Corbusian vision of social paradise, which this replacement for the honeycomb embodied, looked like a beekeeper's nightmare. In it, settlements bore names of quaint old villages obliterated before an advancing army of cranes and scaffolding. There were as yet no

lycées

, only a few scattered and oversubscribed primary schools. Sleepy teenagers from the tower blocks arrived every morning via green city buses at the schools of the inner ring. The historic suburbs with wide tree-lined streets, where Art Deco apartment blocks on the main road hid fine houses with large gardens, were usually referred to as

brda â

the hills â and their gilded youth as

brdjani â

the hillbillies. The bus lines which brought the

peasants â

the inhabitants of the outer ring â into the demesne of the hillbillies of the inner ring bore the names of the old villages which marked their final destinations. Romantic names such as Cerak (Oak Grove), Bele Vode (White Waters), Visnyichka Banya

(Sour Cherry Spa), Veliki Mokri Lug (the Great Wet Copse) and Mali Mokri Lug (the Little Wet Copse) obscured the drab socialist realities of what the Germans called

Trabantenstadten

, Trabant Towns. Bleak blocks of flats smelled of coal and sauerkraut. Amid them, children played on muddy lawns until summoned home by a piercing shout from a distant balcony. At dusk, parental cries multiplied, like the screeching of swallows or bats.

The in-comers from the outer circle normally formed little groups according to the bus routes on which they travelled. Hillbillies, meanwhile, were the offspring of Belgrade yuppies, who, like the children of New Labour in the Britain of the late nineties, preferred to forget where they came from and instead enjoyed the privileges of where they were at the moment. They dressed fashionably, read glossy foreign magazines available only by subscription, drove smart little cars imported from the West and enjoyed holidays abroad or in one or two select spots on the Adriatic coast. The walled old towns were

in

. Any resort with hotels belonging to the trade unions or offering package holidays for the

déclassés

from abroad was

out

. Any foreigner who could afford nothing better than a holiday on the Yugoslav coast was by definition to be looked down on. Membership of the Communist Party was itself clearly coded in the Hillbilly

Book of Etiquette

: as a rule of thumb, it was socially smarter not to join (and particularly smart to endure a meaningless job as a punishment for not joining). I was obviously committing a social

faux pas

of tectonic proportions, but then, owing to my family's somewhat eccentric movements, I was only a tentative hillbilly anyway. I was never entirely sure where I was supposed to belong, so I made a career of not belonging.

In February 1980, in our senior common room new members of the Communist Party represented a more raggle-taggle selection than before. Some were visibly keen, some rather diffident, some were obvious (clever-clogs, careerists with a bad sense of timing, those who carried a briefcase to school, prominent members of youth organizations, children of well-known communists who could hardly afford to refuse to join), some rather less so (ditzy girls from old families who had fallen for the hammer-'n'-sickle chic, the school poet, the fourth-grade hunk, a good third of the school basketball team, encouraged to join as role models and highly visible because they were all six foot six and chewing gum). Working out which members of the teaching staff belonged to the party, information you wouldn't normally have been privy to as a student, was part of the privilege conferred by this particular entry into the adult world. The rest of the evening was a blur. An oath was said, a paper signed, the red carnation dropped into a litterbin on the way home. I still tend to avoid buying carnations whenever I can: they remind me of communists and winter funerals.

A year or two later my membership lapsed through nonpayment of my monthly subscription fees. It wasn't that I couldn't afford the student rates, which were nominal; it was pretty obvious that the party was over, and not responding to the reminders for payment was the most elegant way of getting yourself expelled, if any expulsions ever officially took place, that is â I am not entirely sure. By the time of the first demonstrations of Albanian students in Prishtina in 1981, I had already ceased to pay attention to Ka-Pe-Yot and its sleazy eighties avatars. Long before the wall began to crumble in Berlin, Yugoslavs were busily denying any affiliation with their own Communist Party. You either tended to forget your membership

entirely or put it about that you had been expelled, by the party secretary in person, for saying this or that straight to his or her face. There were usually no witnesses, and the secretaries were hardly likely to raise their heads above the parapet and put the record straight when they themselves were busily composing accounts of the dramatic events which surrounded their own expulsion.

The only people who still went around saying that communism was basically a good idea were the

Informbirovci

, the old communists who remained loyal to Russia at the time of Tito's split with Stalin in 1948 and did their time in the Goli Otok labour camp in the Adriatic as punishment. They were mostly senile and the only other thing they could remember was the Russian lyrics of the Internationale.

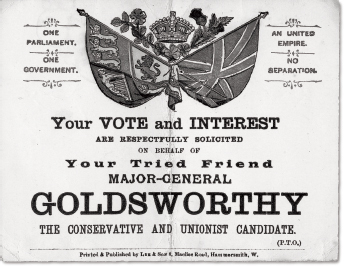

In fact, by the time I settled in England, I managed to forget that I had ever been a communist, and cheerfully supported the Conservative Party campaign in Hammersmith in west London, where I lived at that point, in its efforts to win the 1987 election. My great-grandfather-in-law was the first ever MP for Hammersmith (Conservative,

bien sûr)

, although he was never poor enough actually to live in his constituency. Both a desire for symmetry and an East European allergy to anything that could be described as leftist, which is so often the first phase in our westward movement, can be claimed as mitigating circumstances. Hands-on experience of campaigning was an invaluable initiation into the rituals of Britishness. I was delivering leaflets, canvassing, urging old ladies not to forget to exercise their democratic right, counting âour supporters' in a well-thumbed copy of the electoral roll. The prospective MP was a thoroughly nice chap. I was even introduced to his parents. Championing Maggie Thatcher, by now, probably seems like

something that should be more difficult to own up to than being a fully paid-up commie, but what the hell? Comrades, I am your comrade again, I promise.