Chernobyl Strawberries (4 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

I now realize that our housing and our family were never quite in sync and this seems to me the very essence of the East European condition. Built in the short-lived golden age of Yugoslav socialism, the New House represented an idea rather than an edifice of bricks and mortar. Like a mausoleum, it embodied â literally â my parents' dream of a large extended family, of generations multiplying and staying put, a Mediterranean hubris flying in the face of so much Balkan history and so much displacement. Whenever I think about this, it hurts. I've never even thought, not for a second, of fulfilling their longing for me to go forth â or, rather, to stay put â and multiply. I entertained the very Western idea that my first responsibility is towards my own happiness. I have been paying for this presumption with the small change of guilt every now and then. Of all the languages I know, guilt is the one that my memory speaks most fluently.

Throughout the sixties and the seventies my mother headed the finance department of Belgrade's City Transport Company

and my father was a code-breaker working for the General Staff of the Yugoslav National Army. My sister was, well, my younger sister. My parents' professions may sound quite grand, but they were an ordinary couple, the original yuppies of the sixties' boom, preoccupied with the upbringing of their two daughters and everything that implied â from French and piano lessons (yuppies, as I said) to summer holidays on the coast and winter holidays in the mountains. My family moved from being shepherds to skiers in three generations. This had nothing to do with the socialist transformation of the working classes and everything to do with my grandparents' ultimate realization that only that which is in our heads cannot be taken away. We were pushed so hard we'd have made the same leap on the moon.

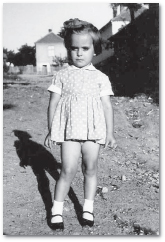

Three years old

My mother's job involved endless hours of overtime, when she was so immersed in bus-fare changes or the implications of zone alteration that she spoke of them all the time

until even my grandmother and I began to discuss the issues involved with some authority. My father's work was so hush-hush that I had no idea what he actually did until I reached my late teens. He worked in a room full of cupboard-sized computers which, I now realize, had collectively less memory than an average PlayStation. In order to visit him in his office, one had to go through multiple security checks, passing solemn men in khaki uniforms along the vast corridors of a forbidding edifice which was bombed to smithereens by NATO back in 1999. My boys smashed Daddy's office. How much more can a father forgive?

Compared to the world of my grandparents, the four of whom managed to live and die in a number of different kingdoms and empires without properly leaving home, all the while acquiring unwanted expertise in the finer nuances of the differences between POW camps, labour camps, concentration and death camps, my own world seemed as dull and stable as something out of a late nineteenth-century bourgeois play. I went to school and did my homework, I read, I played, I collected pictures of film stars and basketball players. Vladimir Visotsky and Robert Redford were my favourites. I marginally preferred the Californian over the Muscovite, not entirely without reservations, which may or may not be telling. The Muscovite was suicidal, the Californian in love with himself.

Even as a ten-year-old, I was attracted to such contrasting extremes of masculinity that it was practically impossible to think of one Prince Charming who could unite all those aspirations into one. The quest for a self-destructive bad boy who would have a steady job, support the family and certainly never ever beat or cheat was soon on. I dressed up, I went out to dances and to concerts, I kept falling in and out of love. I grew my hair long, I cut my hair short. The world was barely moving. I was waiting for my life to begin. I believed in nothing very

much, but â for reasons which I cannot now begin to fathom â I believed in the supreme power of romantic love. That, comrades, is the real opium of the masses: the belief that destiny and not you is uniquely responsible for our happiness; the obstinate belief that love will conquer all. It takes a lifetime to shake off. They peddle it in the West too; it is the most useful of distractions.

My family has lived in the Belgrade suburb of Zharkovo, at the end of the same tramline, for the best part of the last ninety years. A pretty village on the town's edge, it gradually grew into a grim socialist satellite town, a Legoland of ugly apartment blocks full of Serb refugees from Bosnia and Croatia. The only buildings of any beauty were old peasant houses, of which a few were left standing, an old Turkish inn which housed a forlorn cake shop, and one or two pre-war industrial edifices in the style of the European Modern Movement. With their shattered windows and rusty gates, they looked derelict and abandoned but for the fingers of sweet grey smoke pointing towards the changing skies from the tall chimneys.

My paternal grandmother once ran a beet farm which supplied raw material for the local sugar plant, whose building now houses an experimental theatre. Cart-loads of jolly cadavers, plump white bodies speckled with wet earth, made their way from our land in the flood plains of the Sava river, just before its confluence with the Danube, to the grim industrial courtyard dominated by the saw-edged roof line under which molasses boiled and brewed throughout the autumn months. My grandfather worked in a quarry which provided stone for houses and graves in this part of town. Both the homes and the graves were inhabited by recently urbanized, dispossessed peasants and â in small houses with deep verandas

hidden by gardens and vine pergolas â the few professionals needed to look after them: the priest, the teacher, the doctor, the small-time solicitor (wills and property disputes).

In the cemetery on the edge of the village, now bisected by a four-lane motorway, my grandfather's name â Petar Bjelogrlic â was inscribed just to the right of centre on a black marble gravestone back in 1962, and left waiting until 1990 for my grandmother's to complete the celestial symmetry. Petar died at the age of sixty-eight. Fourteen years younger than him, my grandmother Zorka remained a widow for twenty-eight years. In its oval porcelain frame, my grandfather's photograph, taken soon after the Second World War, shows a melancholy, handsome middle-aged man with grey eyes and a blond moustache twirled at the ends. He looks like a reluctant dandy, uncomfortable in his stiff collar and thin black tie. Next to him, in a photograph from the seventies, my grandmother gazes straight to the camera with her coal-black eyes, white hair in a neat chignon, with the faintest of smiles on her lips. She is still wearing her widow's weeds and could almost be his mother. We are forever remembered at the age at which we die, but this particular funerary photographic mismatch makes it difficult to imagine what kind of husband and wife they might have been. I remember Zorka well; Petar, not at all.

He was a bright Serb boy from Herzegovina who was drafted against his will into the Austro-Hungarian army during the First World War. He wound up in Belgrade after the Armistice with hundreds of others in tattered uniforms, victors by virtue of their nationality, losers in their poverty and in every other way. He started off as a porter under the neo-Baroque arches of the central railway station and suffered horrible fits of homesickness, which he eased by seeking the company of his compatriots. There were dozens of young men just like him, newly arrived from the barren uplands of Herzegovina,

in each working-class suburb of Belgrade. Born in the last decade of the nineteenth century as a subject of the Ottoman sultan, Grandpa died a citizen of the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia. Between the crescent moon of Islam and the hammer and sickle of communism, his life changed little. He remained impoverished, hardened by long hours of physical labour, never fully at home.

He was in his late thirties by the time he felt ready to marry. His chosen bride, my paternal grandmother, was a Montenegrin, a fierce little wasp of the best stock that the southern mountains had to offer. On her father's side, her people had been frontiersmen and warriors for generations, and, on her mother's, they were from the Nyegush clan, the ruling tribe of the theocratic Montenegro, providers of a succession of celibate prince-bishops who were Europe's ferocious alternative to the Dalai Lama. The genes of the mothers of all those tall, dark-haired and bearded Orthodox prelates with large silver crosses around their necks and princes with fur pelisses over silver rifle butts lurk in my genetic soup. For Zorka, Petar was clearly an act of rebellion and a half.

Plus ça change

. . .

Zorka's grandfather was given land around the city of Nikshich by Prince Nicholas of Montenegro as a reward for valour in the Turkish wars. Wounded in both legs on the battlefield and unable to move, Grandpa bit the throat of a Turkish soldier who was attempting to cut off his nose and stuff it in his trophy bag, and was duly mentioned in the Montenegrin equivalent of dispatches. Not to be outdone, his son received in his own turn acres of fertile black soil on the Hungarian border as a reward for a good fight in the First World War. In my grandmother's family, different estates are still remembered by the

wars and wounds which brought them into our possession. The trophies came with a bloody string attached. Settlement on frontier land was always to be paid for with a pound of flesh.