Chinese Comfort Women (29 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

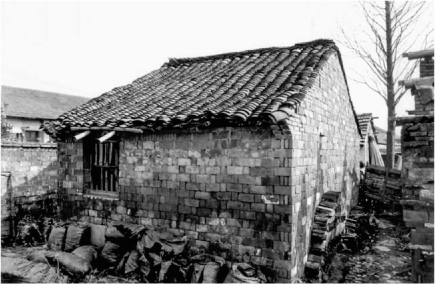

Figure 20

“Comfort station” survivor Zhu Qiaomei’s home after the Second World War; her family became destitute as a result of the Japanese invasion.

There are many cases similar to Nan Erpu’s in Yu County. Wang Gaihe was captured in the spring of 1942 when the Japanese army raided the Chinese Communist Party members’ meeting at Nanbeizi. Wang’s husband, a member of the CCP and anti-Japanese forces, was arrested and shot to death before Wang’s eyes. The Japanese soldiers tried to force her to reveal information about other CCP members, torturing her until she lost consciousness. She was then taken to the Hedong Village stronghold and raped every day. One of Wang Gaihe’s legs was broken, her abdomen became swollen, her teeth were knocked out, and she became incontinent. She was almost dead when her father sold their land and other properties to ransom her. Wang was bedridden for two years after her release, and for another three years she

required support to walk. In her old age, Wang led a lonely life, depending on a small pension of about sixty yuan from the Chinese government,

30

along with the produce from a 0.13-hectare plot of land. For more than half a century, incontinence and pain from her old injuries caused her daily agony, and at night she was haunted by nightmares filled with Japanese soldiers. “I don’t have much time left,” Wang said, “I want to see justice done for my torture while I am still alive.”

31

Wang Gaihe died on 14 December 2007 without having attained that longed-for justice.

The twelve survivors whose experiences are related in

Part 2

all lived in poverty once they escaped or were finally released from military comfort stations. Zhu Qiaomei’s family, for example, became destitute after her husband was killed by Japanese troops and their restaurant was destroyed. For decades they lived in an old, tattered shed. When Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei visited her in 2000, Zhu Qiaomei’s health was declining and she suffered from renal disease and constant headaches. Zhu Qiaomei and her family depended mainly on her son’s retirement pension of 460 yuan (less than US$70 at the time) per month to meet daily living expenses. Other than that, she received financial aid of thirty-six yuan a year from the local government of Chongming County (see

Figure 21

). Chen Yabian lives in a decrepit mud-brick house in Hainan, and daily she eats dark-coloured weeds like those that the interviewers noticed boiling in a big pot in her kitchen in 2000. With no other source of income, Chen Yabian relies on selling coconuts to make ends meet.

In addition to living in poverty, the survivors strive constantly to live with the physical and mental wounds that are the direct result of the torment they endured in the comfort stations. Uterine damage and sterility are common among the victims, and a variety of psychological symptoms, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, chronic headache, insomnia, nightmares, nervous breakdown, and fear of having sex haunt them to this day. More than half a century has passed since Lin Yajin was tortured in the military comfort station, but she still suffers as a result of her traumatic experiences. She rarely smiles and does not like to talk to people. When she was invited to be one of the representatives of the survivors and to attend the opening ceremony of the Chinese “Comfort Women” Archives at Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, in June 2007, she locked herself in her room and did not talk to anyone. Even at mealtimes, she hardly ever said a word to her companions. There was always a sad, absent look on her face. Among the twelve survivors whose narratives are presented in this book, seven have permanent scars or injuries as a result of physical torture in the comfort stations; six suffer from injuries of the uterus or urinary tract as a result of sexual

abuse; seven suffer from constant headaches and nightmares as a result of beatings and/or psychological trauma; three had pregnancies that ended in miscarriages; and five were unable to give birth as a result of the torture experienced in the comfort stations.

Figure 21

“Comfort station” survivor Zhu Qiaomei was sick at home in 2001.

Being unable to bear children is especially significant in a society in which one becomes dependent on one’s children for care in one’s old age. Childlessness often relegates a survivor to devastation and decreases her societal value since, traditionally, a woman’s worth is determined by her ability to produce offspring. Gao Yin’e, a native of Nanshe Township, Yu County, was married when she was kidnapped in the spring of 1941 by the Japanese troops stationed in the stronghold in Hedong Village. Her husband sold their land to raise money for her ransom. By the time she was released, sexual abuse had already caused her serious damage; Gao Yin’e suffered severe abdominal pain and irregular bleeding, but her family had no more money to obtain treatment. Gao became sterile and, consequently, was divorced because she could not bear children. She remarried but was divorced again for the same reason. During her third marriage Gao adopted a daughter. However, her family never overcame economic hardship;

32

on 14 January 2008, Gao Yin’e died in poverty.

An oppressive socio-political environment added another level of misery to many survivors’ lives. It is true that, in the postwar era, some survivors did receive warm support from local people. For example, Grandma M, a Korean woman who adopted a Chinese name, was tricked into a Japanese military

comfort station in Wuhan, Hubei Province, in May 1945. She escaped three months later during the chaos of Japan’s surrender in August 1945. Feeling disgraced because she had been a comfort woman, she did not return to Korea and settled in Huxi Village, Hubei Province. Over the years she received affectionate support from the local people and was covered under the village’s Five Guarantees Program. The local Civil Administration Department has provided her with a monthly allowance of sixty yuan for living expenses. The villagers call her “grandma,” and she proudly considers herself to be Chinese.

33

However, in many cases the former comfort women faced social and political discrimination. The patriarchal ideology that permeated Chinese society rated a woman’s chastity higher than her life. Thus, a woman whose virginity was spoiled or whose chastity was violated became socially unacceptable. During the war, this patriarchal ideology was combined with political prejudice, with the result that many comfort station survivors were regarded not only as immoral but also as betrayers of the nation. The survivor’s family was also affected; reportedly, three of Nan Erpu’s family members in Yu County were killed by unknown assailants because she was a military comfort woman.

34

In this social and cultural environment, many comfort station survivors felt so ashamed that, after the war ended, they lived alone and in silence. Often, they did not even speak to their families. Unable to overcome the horrible memories and emotional distress, some survivors receded into insanity or committed suicide. Those whose wartime experiences were revealed were often humiliated and persecuted. After the war, as has been mentioned, Yuan Zhulin was accused of having “slept with” Japanese soldiers and was sent to the far north to perform hard labour. Nan Erpu was charged as a “counterrevolutionary” because she had serviced Japanese soldiers. She was imprisoned for two years and persecuted as an “old-line counter-revolutionary” during the Cultural Revolution. Unable to bear the physical and mental agony resulting from her wartime torture and postwar mistreatment, Nan committed suicide in 1967.

35

Patriarchal ideology, and the sexism that is inseparable from it, is still so widely influential in Chinese society that, when victim Li Lianchun was invited to attend the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery in Tokyo in 2000, the local official refused to issue her the necessary travel documents because he believed it was inappropriate for her to speak of her “shameful past” abroad.

36

This patriarchal sexism almost certainly plays a role in explaining why China, as the largest victimized nation, failed to pursue timely justice for the hundreds of thousands of Chinese comfort women. Although the “Committee for Investigating the Enemy’s War Crimes” (

Diren zuixing diaocha weiyuanhui

),

established by the Chinese Nationalist government at the end of the war, listed “Rape,” “abduction of women,” and “Enforced Prostitution” as war crimes,

37

there was no thorough investigation into what had occurred in the comfort stations.

38

International and domestic social, political, and cultural postwar conditions ensured that survivors suffered in silence. However, these conditions began to change, and, inspired by the international redress movement in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the endeavour to seek justice for the victims of the Japanese military comfort women system has finally gained momentum in China.

9 The Redress Movement

The sexual slavery practised by the Japanese military was largely unrecognized during the first decades after the Second World War. While descriptions of comfort women occasionally appeared in memoirs and literary texts in Japan, most of the victims and former Japanese military men remained silent about the issue. In the 1970s, two pioneering books on the subject were published, one by Senda Kakō, a Japanese journalist and non-fiction writer, and the other by Kim Il Myon, a Korean resident in Japan.

1

In addition, three personal stories of former Japanese and Korean comfort women were published in Japan.

2

Memoirs of former Japanese officers, who describe their wartime involvement in establishing the comfort stations, have also been published.

3

Yet the issue failed to attract wide public attention until, in the 1980s, a coalition of Korean and Japanese women’s groups elevated it to the status of a political movement within the global context of feminist and grassroots politics.

4

The South Korean Church Women’s Alliance initiated action to condemn sexual violence against women, defining it as a basic human rights issue, and Professor Yun Chong-ok, who had engaged in years of research on the comfort women issue, started to work with some concerned Japanese scholars.

5

The Japanese government initially denied any involvement with comfort women and dismissed the request for an investigation when Motooka Shōji, a Socialist Party member of the Japanese National Diet, raised the issue at a budget committee meeting on 6 June 1990. The government was forced to change that position after a series of key events over the following year and a half. In August 1991, a Korean woman, Kim Hak-sun, came forward to testify publicly about her experience as a military sex slave. On 6 December 1991, Kim and two other Korean comfort women survivors filed a lawsuit against the Japanese government at the Tokyo District Court, asking for an apology and compensation. This was the first of a series of lawsuits filed by surviving Korean comfort women against the Japanese government. About a month later, on 11 January 1992, a major Japanese newspaper,

Asahi Shimbun

, reported Chūō University professor Yoshimi Yoshiaki’s finding of documentary evidence of the Japanese military’s direct involvement in establishing the

comfort women system. Five days after the publication of Yoshimi’s findings, Prime Minister Miyazawa Kiichi expressed his regret and extended an apology during his visit to South Korea, promising further investigation of the issue.

On 6 July 1992, the Japanese government published the result of its investigation, which involved an examination of 127 documents, including those first unearthed by Professor Yoshimi and other investigators.

6

However, critics are sceptical about the results; as George Hicks notes, there were no relevant documents released from the Police Agency or to the Ministry of Labour, even though these two government agencies were frequently implicated in the forced recruitment of women.

7

In addition, the Ministry of Justice was not investigated, although it was known to house the records of the war crimes trials. The investigation also failed to include data from individuals (such as telephone reports collected in Japan) and from foreign documents (such as US Army reports).

8

Not surprisingly, the limited scope of the investigation provoked widespread criticism from women’s groups and concerned researchers.

9