Chinese Comfort Women (25 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

During that time I didn’t see any woman given a medical examination in the station, nor did I see any man ever use a condom. I didn’t know if any of the girls became pregnant, but I knew one woman, whose name was Chen Youhong, who was tortured to death. She didn’t want to do what the Japanese soldiers told her to do, so she was beaten until blood gushed out of her vagina. She bled to death. I heard that another girl committed suicide by biting off her own tongue.

The Japanese soldiers never gave us anything or any money. They didn’t even give us enough to eat, never mind paying us. I was kept in the Tengqiao Comfort Station for a long time, at least two years, until I became very sick and my family helped me escape. That was around the Fifth or the Sixth Lunar Month of the year. That day Huang Wenchang from my home village came to see me. He told me that my father had died. I cried loudly and bitterly, and went to beg the Japanese officer to let me go home to attend my father’s funeral. The officer wouldn’t let me at first, but Huang Wenchang and I begged and begged, kneeling on the floor to kowtow. Finally he agreed to let me go, with the condition that I would return to the comfort station as soon as my father’s funeral was over.

That was in the evening. Huang Wenchang took me out of Tengqiao and, via a shortcut, towards home. We arrived at my home in the middle of the night. As I walked through the door, I was stunned to see my father in perfectly good health waiting for me. It turned out that my father and Huang Wenchang had made a plan to rescue me from that comfort station by deceiving the Japanese troops. They were afraid that I would have been unable to act as if it were real, so they didn’t tell me the truth until I got home.

My father and Huang Wenchang worked overnight with hoes and shovels to make a fake grave for me on top of a desolate hill on the outskirts of the village. They told people that I had committed suicide because of excessive grief. My father and I fled from the village right after that. My mother had already died by that time. My father and I became fugitives and for a period lived as beggars. We stayed in one place for a while then returned to Jiama Village. People in our village told us that the Japanese officer “Jiuzhuang” had come with a group of soldiers to arrest me. The villagers told him that I had committed suicide. He saw the fake grave and believed them.

Since everyone in the village knew that I had been ravaged by the Japanese troops, no man in good health or of good family wanted to marry me. I had no choice but to marry a man who had leprosy. My husband knew about my past and used it as an excuse to beat and curse me for no reason other than that he was unhappy. I gave birth to five children: three daughters and two sons. Two of my older daughters are married and the youngest one is still living with us. My children have treated me well, particularly my daughters. However, since I had that horrible experience in the past, even my own children sometimes swear at me. But it was not my fault! What a cruel fate! I hate the Japanese soldiers!

During the Cultural Revolution, because of my awful past, people in the village, particularly those in the younger generations who weren’t clear about history, said bad things about me behind my back; they said I was a bad

woman who slept with Japanese troops. Because of this, my husband was not allowed to serve as a village official and my children were not allowed to join the Communist Youth League or the Communist Party.

I am willing to go abroad to testify to the atrocities the Japanese military committed, and I am also willing to go to Japan to testify to the faces of the Japanese. I demand an apology from the Japanese government. I am not afraid. [Visibly cheered by this idea, Huang Youliang’s previously expressionless face broke into a big smile.]

After her interview in 2000, Huang Youliang led the interviewers to the site of Tengqiao military comfort station. The former comfort station is a run-down, two-story building made of bricks and wood; its roof and entrance door are gone. Local residents confirmed the accuracy of her recollection about the comfort station. The Japanese army’s blockhouse and water tower nearby are still standing. Although Huang Youliang had not been allowed to leave the comfort station during her captivity, she had been able to see outside from the second floor of the building. She pointed and said, “Look, see that tree trunk over there? It was where the Japanese troops tied up and tortured their captives.” On 16 July 2001, Huang Youliang and seven other Japanese military comfort station victims from Hainan Island filed a lawsuit against the Government of Japan in the Tokyo District Court. Huang Youliang is now living with her youngest daughter in Hainan

.

(Interviewed by Chen Lifei and Su Zhiliang, interpreted by Hu Yueling in 2000)

Chen Yabian

Chen Yabian was abducted from Zuxiao Village and sent to the Japanese military comfort station in Ya County (today’s Sanya) on Hainan Island. From February 1939, the Japanese military stationed a large number of troops in Ya County, using it as a major naval and air force base

.

5

It has been confirmed that fourteen Japanese military comfort stations were in operation in the area between 1941 and 1945. During a research trip in 2000 Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei were able to locate seven of the buildings or what is left of them

.

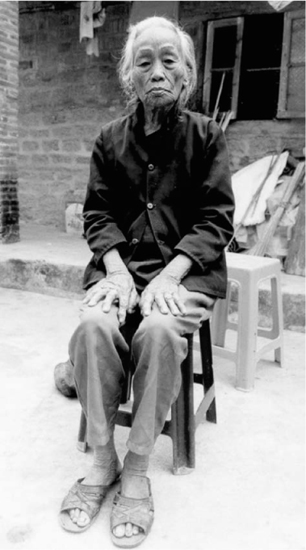

Figure 17

Chen Yabian, in 2003, in front of her home.

I live in Zuxiao Village, Lingshui County, Hainan Island. I had one older brother and one older sister; I was the youngest child in the family and my parents loved me very much. People said I was a good-looking girl.

During the occupation, the Japanese army organized a puppet self-guard corps in the vicinity of Zhenban-ying Village. [According to the local historical record, the Self-Guard Corps comprised about fifty soldiers and was led by Chen Shilian.] They set up barracks on the hill near our village and ordered local collaborators to draft young women to work in the barracks. One day in 1942 four traitors came to my home and said that the head of the Self-Guard Corps had ordered me to harvest grains. Many girls from the Li ethnic villages in the area were taken into the barracks, including another girl from my village and me. I was forced to work there for months, doing all sorts of miscellaneous jobs, such as washing clothes, sewing gunnysacks, carrying water, and processing grains. At night girls were forced to “entertain” the soldiers. We never received any payment for the work we did at the camp.

After working in the corps camp for a few months, I was taken by force to a Japanese military comfort station in Ya County and locked in a dark room. I didn’t know where in Ya County the station was. I only remember that it was a two-story wooden house and that I was held in a small room on the second floor. In the room there was a shabby bed, on which there was a very dirty quilt. There were also a table and two stools. The door was locked and the window was sealed completely with wooden boards, so the inside was pitch black even during the day. Japanese soldiers came at night, sometimes two or three, sometimes more. They made me bathe first and then raped me one after another. Some of the soldiers seemed to have been from Taiwan. The Japanese soldiers didn’t wear condoms when they raped me, nor did the army provide me with medical examinations. I was so frightened and resisted them, but they encircled my neck with their hands, strangling me, and slapped my face … [Chen Yabian stopped talking and cried. She demonstrated how the soldier strangled her.] I cried aloud and tried to push the door open, but the door was locked from outside. From that day on I was never allowed to step outside. They only opened the door to deliver a pail when I needed to move my bowels or to send in some food for me to eat. They sent food twice or three times a day, but I don’t remember what the food was like; it was so dark in the room that I couldn’t even see the food clearly.

I cannot remember clearly how long I was kept in the Japanese comfort station, perhaps for several months. I cried in horrible fear every day there. My parents were worried to death after I was taken away. They begged everyone they could possibly find to help obtain my release, but there was no hope. After having begged many people for help, but to no avail, my mother went

to the head of the corps and kneeled before him. She cried, begged, and said she would die in front of him if he refused to help obtain my release. The head had no way to get rid of her so he, in turn, went to beg the Japanese troops and helped arrange my release.

I could not walk upon my release; my lower body was severely infected and was so swollen that I could not relieve my bowels without excruciating pain. My eyes were damaged by the torture in the comfort station, too. For all these years after the war my eyes have been red and have hurt; I cannot see clearly and my eyes water constantly. Yet I was drafted by the corps again after I was released from the comfort station and forced to work at the corps camp for another three years until Japan’s surrender. [Su Guangming, chair of Lingshui County People’s Political Consultative Committee, told the interviewers that Chen Yabian, fearing discrimination because she was a Japanese military comfort woman, lived alone in the mountains for a long time until local people prevailed on her to emerge after the liberation.]

My parents arranged for me to marry Zhuo Kaichun when I was a child. [Pang Shuhua, who was the interpreter for the interview, explained that this was called “child-engagement” (

wawaqin

), a local custom whereby parents pre-arranged a marriage for their children in their childhood.] Zhuo Kaichun joined the Chinese forces when I was detained in the comfort station. He later left the Chinese force because one of his hands had been injured. We married after he returned home.

I had terrible difficulties trying to have a child after my marriage. [Chen Yabian cried again.] I had multiple miscarriages and stillbirths. Doctors said my uterus had been damaged by the torture. I always had severe pain during menstrual periods and intercourse. When I became pregnant again in my late thirties, my husband sent me to a hospital in central Hainan, and, under the doctors’ diligent care, I finally gave birth to a healthy girl around 1964.

My husband died several years ago and my daughter is married and lives in another village now. I am in very poor health. I continue to have abdominal pain all these years later, and I have difficulty breathing. I also suffer from frequent nightmares resulting from the past horrors and constant fears. During the Cultural Revolution I was beaten and yelled at by local people. They tied up my hands and pushed me out, accusing me of “having slept with Japanese soldiers.” How miserable I am for not having a son to look out for me …

[Chen Yabian cried again. According to local tradition, male offspring take care of aged parents while daughters move away from their parents’ home after marriage. Although Chen Yabian is covered under the Five Guarantees Program – a social welfare program that guarantees childless

and infirm elderly people food, clothing, medical care, housing, and burial expenses – because of the high cost of her medical expenses the financial aid she has received from the government is insufficient to meet her needs.]

I could have had many children, but because of the torture by the Japanese troops I was unable to have a son. I want redress. I welcome all who come to interview me because I want to let people know my experiences. I demand an apology and compensation from the Japanese. I want to have a peaceful and good life in my late years.

On 30 March and 1 April 2000, Chen Yabian attended the First International Symposium on Chinese Comfort Women at Shanghai Normal University as an invited speaker. She had to rely on pain medication to ease her headaches, but despite the constant discomfort she gave a courageous speech on her wartime experience to an international audience. In poverty and poor health, Chen Yabian now relies on the “Five Guarantees Program” provided by the local government and the produce of a few fruit trees for daily life. She lives with constant body ache and abdominal pain, and continues to have horrifying nightmares

.

(Interviewed by Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei and interpreted by Pang Shuhua in 2000 and 2001)

Lin Yajin

Lin Yajin was kidnapped and imprisoned in the Dalang stronghold at Nanlindong (today’s Nanlin Township), Baoting County, Hainan Island, in 1943, which was also the year that the United States began submarine warfare against Japanese shipping

.

6

In order to reinforce its military bases on Hainan Island, the Japanese army brought more troops from northeastern China to the area that same year. Nanlin, which is only about twenty-five kilometres from (Ya County) Sanya and is surrounded by mountains, was chosen by the Japanese army as a base for military supplies and munitions. The Japanese troops drove the villagers out of their hiding places in the mountains. Villagers who didn’t obey the military orders were killed. Those who followed the orders to register for a “Good Citizen ID” were sent to do hard labour on military highway construction sites, in iron mines, or on farms, where they grew tobacco, grains, and vegetables for the Japanese army

.

7

Lin Yajin had been drafted to labour at a military highway construction site before she was kidnapped and taken to a military comfort station

.