Chinese Comfort Women (26 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

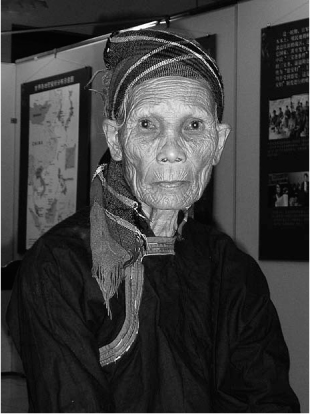

Figure 18

Lin Yajin, in 2007, attending the opening ceremony of the Chinese “Comfort Women” Archives in Shanghai.

I am a Li ethnic woman, born in Fanyuntao, Nanlindong, Baoting County, Hainan Island. My father’s name was Lin Yalong, and my mother was Tan Yalong. I had five siblings. My older sister was named Yagan. I am the second child. I had two younger sisters and two younger brothers. My parents and most of my siblings have already died. Now only my youngest brother and I are still alive. I am living in Shihao Village in Nanlin District now. I don’t have any children of my own. My siblings’ children all live in Nanlin. They come to visit me when I need help.

I was about sixteen years old when the Japanese troops came to Nanlin. Three years later [1943], I was drafted by the Japanese military to build a highway that led to their arsenal. Many people in our area were drafted, including a lot of women. We received no pay and had to bring lunch to work from home. I was released two months later.

In the autumn of that year, I heard gunshots from the direction of Da’nao Village when I was harvesting rice with three girls named Tan Yaluan, Tan Yayou, and Li Yalun from neighbouring villages. [The names are transliterated according to Lin Yajin’s pronunciation.] We realized that the Japanese troops had come. The rice paddy was very close to Da’nao, so we had no time to escape. We lay down next to the ridge between the fields, very scared. A long time passed. When we heard some sounds and raised our heads to look around, we found Japanese soldiers standing right behind us. The Japanese soldiers tied our hands behind our backs with ropes and took the four of us to their strongholds, first to the Japanese army’s barracks at Nanlin and then to the Dalang stronghold in Ya County. I was nineteen years old at the time. [“Dalang” is the place-name “Shilou” in Li language].

We spent one night at the Nanlin stronghold in a room that was used to incarcerate labourers who attempted to escape. We saw torture instruments and feet cuffs. The Japanese soldiers placed the cuffs on our feet so that we could not move. The cuffs would break your bones if you sat down, so we could only stand. An interpreter who looked to be a native of Hainan came in and said to us: “Do not try to run away. You will be killed if you try to escape.”

The following day, we were taken to the Dalang stronghold in Ya County by armed Japanese soldiers. The Japanese soldiers tied us up and forced us to walk very fast. They kicked us ruthlessly if we slowed down even a bit. We left Nanlin in the morning and arrived at Dalang when it turned dark. We were not allowed to eat or drink the whole day.

At Dalang we were locked up in a strange house. The house was divided into small rooms. Each girl was put into a room. The room had a wooden

door but no window, so it was very dark inside. The door was double-locked and there were always Japanese soldiers standing outside guarding the house. The walls felt like metal sheets. The size of the room was about this big. [Lin Yajin indicated a length of about ten square metres.] There was no bed or bedding in the room. They only gave me one washbowl and a towel, and there was a container for urination at the corner of the room – nothing else. I slept on the earthen floor. Luckily the weather was not cold.

The Japanese soldiers only took me out of the house to empty the excrement container. They watched me closely and took me back when I was done. The room was filled with a filthy smell. After I was taken into the stronghold I was not given clothes. The only clothing I had on me was the top shirt and skirt I was wearing when I was abducted, which were almost torn into pieces by the Japanese soldiers later; both sleeves were ripped off.

Twice a day the Japanese soldiers sent us food. It was thin gruel served in a coconut shell. It smelled awful and looked like swill. Our first meal each day was near noon. The Japanese soldiers would come after we had eaten the meal and had emptied the excrement container. Normally three or four Japanese soldiers would come into my room together. One of them would guard the door. The others often fought to be the first to rape me. I was very frightened when they fought, so I stood against the wall to avoid being hurt. They were completely naked, one raping me while the others were watching.

[Lin Yajin cried. She squinted into the distance, and tears flowed from her eyes. Heartbreaking sobs filled the room. After about twenty minutes, Lin calmed down and continued.]

Some of the Japanese soldiers raped me more than once. At night a different group of soldiers would come. They never used condoms, but they gave us some pills to take. The pills were about the size of my pinkie nail, some white, some yellow, and some pink. I feared that the pills might be poisonous, so I spit them out when no one saw it. We were given a bowl of cold water to wash our lower bodies after each group left. I had already begun menstruating at that time. I resisted fiercely when I had my menstrual period, but the Japanese soldiers raped me even when I was bleeding. I developed some kind of disease and had horrible pains when urinating. The lower part of my body became swollen and festered.

The Japanese soldiers often beat me. If I showed the slightest resistance, they would grab my hair and hit my face and breasts. One day a Japanese soldier came to rape me, but I resisted. He punched my left breast so hard that my chest continues to hurt today. [Lin showed where she had been hit. The bones on the left side of her chest were noticeably uneven; the entire

area looked bumpy while some parts were caved in. Lin cried again. Her whole body trembled like a leaf in the wind.]

One time a Japanese soldier pressed me to the floor with a cigarette between his lips. He crushed the cigarette onto my face. The burned area immediately swelled up. The wound left this scar next to my nose. [The scar, which is about the size of a large pea, is clearly visible on Lin’s face.] No Japanese doctor ever gave us a medical exam or any treatment. If a girl fell sick, she would be thrown into cold water. As time passed I began to urinate blood and I had severe chest pains. The pain went from my chest to my left shoulder. Even today my chest often hurts, bringing back horrible memories of the past.

I was locked in the Dalang stronghold for a long time. Mother told me later that it was about five months. I cried every day. I also heard the crying of the girl in the next room and the sounds of the Japanese soldiers violating her since the rooms were separated only by metal sheets. Every night we cried in our rooms, talking about our parents, our families, and our fears that we might never see them again. I was already very sick. My injured chest bones hurt, my private parts festered, I urinated blood, and my whole body was swollen and ached like hell. I thought I was going to die soon.

My father heard that I was very sick, and he begged a relative who was a Baozhang to bail me out. [Baozhang was an official position in the old

Bao Jia

. administrative system, which was organized on the basis of households. Each

Bao

consisted of ten

Jia

and each

Jia

consisted of ten households. The Baozhang was the head of the

Bao

.] My father and the parents of the other girls sent chickens and rice, which were the best things they could find, to the Baozhang. The Baozhang, in turn, brought these things to beg the Japanese troops to let me and the other three girls out of the Japanese stronghold. By that time the four of us were all infected with the same disease and we were too ill to service the soldiers, so the Japanese troops let us out. I was too sick to walk and was carried back by members of my family. Yayou died soon after she got home. Yaluan and Yalun also died within a year. I was the only one who survived.

My father died not long after I was released from the Japanese stronghold. He had had a chronic disease and constantly had chills and a fever. After I was kidnapped by the Japanese troops, my father did hard labour for the Japanese army, hoping to earn my release. His health declined rapidly because of that. He did not live to see Japan’s surrender.

I stayed in the Baozhang’s village for about two months, receiving herbal treatments, but the infected area didn’t heal and I continued bleeding. My mother then brought me back home. She gathered herbs to treat me herself.

I was so sick that I was unable to walk for a long time and had a bloody discharge with pus. My mother dug up herbs in the mountain, put them in liquor, and then used this herbal wine to treat my disease. She also invited someone to perform sorcery. Gradually I recovered, and by the spring of the following year, I was able to walk.

My mother helped me recover, but she fell sick. She died two years later. I wailed loudly in front of my mother’s tomb. Life became much harder after my mother died. My older sister was already married at the time and lived in far-away Fanshabi Village at the foot of the mountain. Seeing the hardship my younger siblings and I suffered, she took me to her house. I lived with my older sister for about four years and met my late husband there.

My husband’s name was Ji Wenxiu. He was from a well-off family that owned some rice land and betel nut trees, so he and his younger brother were able to attend school. His family paid for everything for our wedding.

8

Because of my past experience, I was afraid to be with him on our wedding night even though I knew this would be totally different because I was married to the man I loved. Still, I didn’t want to tell him about my past. My husband had heard about what had happened to me, but he never asked me about it. He didn’t want to hurt me. He was really nice to me. I became pregnant soon, but two months into my pregnancy I had a miscarriage.

Two years after I married Ji Wenxiu, he went to work in Ganzha. His younger brother was a military man at the time and he asked my husband to join him in doing work for the revolution. My husband helped collect grains for the Liberation Army and worked at the local tax bureau. He was later arrested when working as the head of the tax office. [Tears filled Lin’s eyes when she was speaking about her husband. The interpreter explained that Ji Wenxiu was one of the many persons wronged during the chaotic 1950s, and it is still not clear why he was arrested.]

I received a note that my husband died of illness in the prison. I couldn’t believe it and went to Baoting to look for him but was told that he had been moved to Sanya. I then went to Sanya, only to find that he had been sent to Shilou. I didn’t know of a way to make the trip to Shilou, so I had no choice but to return home. I don’t know exactly when my husband was arrested and died. I only remember that it was during the time when everyone was eating from the same big pot.

9

Because of my husband’s arrest I was discriminated against. When eating in the communal dining room, I was always given a smaller portion and worse food. I did farm work to support myself. Although I worked very hard, I was given the lowest number of work-points.

10

I was living with my in-laws at the

time. My father-in-law had some land before the revolution so his family was classified as being of landlord status. His lands had been confiscated, but because of his family background, he was criticized and denounced at public meetings during the Cultural Revolution. When my in-laws died, no one in the village came to attend their funerals. My husband had seven siblings. Now all of them have died except his younger brother.

An investigative team came to check into my history during the Cultural Revolution. However, the three girls who were abducted by the Japanese along with me had all died. The investigative team couldn’t find any witnesses. Moreover, those who knew I had serviced the Japanese troops didn’t tell the team anything because most people in the village belonged to the same Ji family. Even today, people in my village don’t like to talk to strangers. Therefore, I was not criticized publicly during the Cultural Revolution. I felt helplessly alone so I adopted a five-year-old boy named Adi from Fanyuntao after the Cultural Revolution ended. Adi has six children now, four boys and two girls. Adi’s oldest daughter has two children already.

The Japanese soldiers did horrible things to me. The Japanese government must admit the atrocities it committed and compensate me before I die.

Since 2000, every month the Research Center for Chinese “Comfort Women” has sent two hundred yuan to Lin Yajin and other Japanese military comfort station survivors in China, using funds from private donors. With that money Lin’s adopted son gradually rebuilt their house. Lin Yajin now lives with the family of her adopted son

.

(Interviewed by Chen Lifei and Liu Xiaohong in 2007; interpreted by Chen Houzhi.)

Li Lianchun

Yunnan Province is situated between inland China, Burma, and India, and it occupied a key position on one of China’s major supply lines during the Resistance War. In 1942 and 1943, the US Air Force built air bases in Yunnan, from which the Fourteenth Air Force provided assistance to Chinese military operations. The Japanese air units countered with major strikes, and the Japanese ground forces began the invasion of Burma in January 1942. The 56th Division entered Yunnan Province in the spring of the same year, and, by early 1943 it had taken control of the area west of the Nu-jiang River (known as Salween River in English) and established its headquarters at Longling

.

11

During the occupation the Japanese troops set up comfort stations from the Longling county seat all the way to the Songshan frontline

.

12

Li Lianchun, whose home village of Bai’nitang lay to the west of Songshan and on the west bank of the Nu-jiang River, was abducted into one of these military comfort stations

.