Cleopatra (20 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

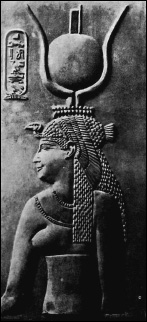

The 30th Dynasty temple of Hathor at Dendera had been substantially redesigned by Auletes, who started building works on 16 July 54 and died just four years into the programme. Work at the temple continued throughout Cleopatra’s reign and was eventually finished a decade after her death. Here, on the outer rear wall of the temple, we find the above life-size double scene of Cleopatra and Caesarion mentioned in

Chapter 2

(page 65). Mother and son are offering to a line of gods. In the left-hand scene they offer to Osiris, his sister-wife Isis and their son Harsiesis; in the right-hand scene they offer to Hathor, her son Ihy/Harsomtus and the Osirian triad (Osiris, Isis and Horus). Hathor, in this context, may be read as a representative of female royal power and solar authority, while Isis represents the universal mother. Between the two lines of gods, in the middle of the wall, is the head of Hathor, the main goddess of the temple complex.

Ptolemy Caesar, as king, takes the dominant role in the offering

scene, a role which Cleopatra has previously denied both Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV and which she reverses in the accompanying text, where she is mentioned before Caesarion. The texts, we may assume, follow actual practice, while the illustration follows the time-honoured Egyptian tradition that will always place a ruling king ahead of his supportive mother. Nevertheless, tradition or not, it seems reasonable to assume that Cleopatra approved the temple artwork. Dressed in a long kilt and double crown plus ram’s horns, Caesarion stands in front of his mother to make an offering of incense to the gods. Above Caesarion hover the protective deities Horus (left-hand scene) and the vulture goddess Nekhbet (right); immediately behind him stands a tiny male figure, his

ka

or spirit. Standing behind her son’s

ka

, Cleopatra wears a tight sheath dress, tripartite wig and a

modius

with multiple uraei, solar disc, cow horns and double plumes. She carries a sistrum and the stylised necklace known as the

menyt

which is associated with Hathor, and she does not have a

ka

figure. Work on this entirely Egyptian scene started in 30, the year that both Cleopatra and Caesarion died, and was continued under Octavian. The message is not a subtle one. Hathor the mother goddess of the Dendera temple is a single parent: the partner of Horus, who lives in his own temple many miles away at Edfu (Greek Apollinopolis Magna). Each year, at the Festival of the Beautiful Union, the cult statue of Hathor would process to the river and sail to Edfu. Here she would reside in the temple with the father of her child for fourteen days, before returning by river to Dendera. Parallels between the earthly triad of Cleopatra, Caesarion and the absent Caesar, and the divine triad of Horus, Hathor and Ihy/Harsomtus are clear. Meanwhile, at Edfu, scenes carved into the temple walls, and the annual celebration of the victory of Horus over his father’s killer Seth, served to hammer home the message of the avenging royal son.

The Dendera Cleopatra is a deliberate mixture of queen, mother and goddess. In 1873 the novelist and journalist Amelia B. Edwards

hired the

Philae

– a large flat-bottomed

dahabeeya

boat – and embarked upon a lengthy, leisurely cruise along the River Nile. Four years later she published an eminently readable account of her travels.

9

Visiting Dendera, she despaired at the damage wrought by the early Christians, who had hacked away at the stonework in an attempt to erase all trace of the temple’s pagan gods:

…one can easily imagine how these spoilers sacked and ravaged all before them; how they desecrated the sacred places, and cast down the statues of the goddess … Among those which escaped, however, is the famous external bas-relief of Cleopatra on the back of the Temple. This curious sculpture is now banked up with rubbish for its better preservation, and can no longer be seen by travellers. It was however, admirably photographed some years ago by Signor Beati; which photograph is faithfully reproduced in the annexed engraving. Cleopatra is here represented with a headdress comprising the attributes of three goddesses; namely the vulture of Maut [Mut] (the head of which is modelled in a masterly way), the horned disk of Hathor, and the throne of Isis … It is difficult to know where the decorative sculpture ends and portraiture begins in a work of this epoch. We cannot even be certain that a portrait was intended; though the introduction of the royal oval in which the name of Cleopatra (Klaupatra) is spelt with its vowel sounds in full, would seem to point that way …

There was a good reason why Miss Edwards could not see the famous

Cleopatra portrait

in situ

. It did not exist. The ‘queen’ beneath the complicated crown (a vulture headdress topped by a

modius

crown with multiple uraei, a solar disc, cow horns and the ‘throne’ symbol of Isis) was actually the goddess Isis herself. The Cleopatra cartouche was a modern enhancement, added to a plaster cast of the original scene by an enterprising curator at Cairo Museum.

10

Unfortunately, Miss Edwards had allowed her assumed knowledge to influence her perceptions:

Mannerisms apart, however, the face wants for neither individuality nor beauty. Cover the mouth and you have an almost faultless profile. The chin and the throat are also quite lovely; while the whole face, suggestive of cruelty, subtlety and voluptuousness, carries with it an indefinable impression not only of portraiture, but of likeness.

A good description of Cleopatra perhaps, but less appropriate for the healing mother goddess Isis.

The classical authors are agreed that Cleopatra occasionally dressed in the ceremonial robes of Isis. Quite what these robes might have been is not made clear. The traditional Egyptian Isis, as seen at Dendera, wore a simple white linen sheath dress, an assortment of jewellery, a heavy tripartite wig and either her ‘throne’ sign or the vulture headdress,

modius

, double plumes, cow horns and solar disc borrowed from Hathor. This image may be compared with a marble statue recovered from Alexandria and dated to the mid-second century

AD

(and now in the Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria) which shows a Hellenic Isis wearing a wig of corkscrew curls, a crown composed of a solar disc, cow horns and double plumes, and a flowing woollen chiton or robe covered with a rectangular mantle or shawl tied with a distinctive knot which, as a symbol of magical power, had come to symbolise the goddess. A colourful Graeco-Roman Isis is described in

The Golden Ass

, written by Lucius Apuleius in

c

.

AD

155.

Here, in Adlington’s 1566 translation, Isis, Queen of Heaven, appears to Lucius in a dream:

I purpose to describe her divine semblance, if the poverty of my humane speech will suffer me, or her divine power give me eloquence thereto. First shee had a great abundance of haire, dispersed and scattered about her neck, on the crowne of her head she bare many garlands enterlaced with floures, in the middle of her forehead was a compasse in fashion of a glasse, or resembling the light of the Moone, in one of her hands she bare serpents, in the other, blades of corne, her vestiment was of fine silke yeelding divers colours, sometime yellow, sometime rosie, sometime flamy, and sometime (which troubled my spirit sore) darke and obscure, covered with a blacke robe in manner of a shield, and pleated in most subtill fashion at the skirts of her garments, the welts appeared comely, whereas here and there the starres glimpsed, and in the middle of them was placed the Moone, which shone like a flame of fire, round about the robe was a coronet or garland made with flowers and fruits. In her right hand shee had a timbrell of brasse, which gave a pleasant sound, in her left hand shee bare a cup of gold, out of the mouth whereof the serpent Aspis lifted up his head, with a swelling throat, her odoriferous feete were covered with shoes interlaced and wrought with victorious palme.

11

Robert Graves’s 1950 more down-to-earth translation of this same text clarifies the description to a moon-disc crown held in place by twin snakes (evolved cow horns?), and a multicoloured robe with an embroidered hem of fruit and flowers covered with a pleated black mantle tied in an Isis knot. Plutarch confirms this: ‘the robes of Isis are variegated in their colours, for her power is concerned with matter which becomes everything and receives everything, light and darkness, day and night, fire and water, life and death.’

12

Faced with a choice of two very different costumes, it seems likely, then, that

Cleopatra would choose the dress, either Greek or Hellenistic, which would best suit her intended audience.

The Ptolemies never neglected Egypt’s traditional temples. Their support for the native priesthood ensured that the elite Egyptians were in turn able to support the artists and craftsmen who preserved Egypt’s cultural heritage. Kings continued to maintain and restore the cult temples of the state gods, while the elite used their wealth to build stone tombs and commission statues and stelae just as their predecessors had always done, but everything now had a distinct Hellenistic twist. The walls of the elite tombs show Greek-inspired figures participating in traditional Egyptian scenes and accompanied by hieroglyphic texts. The temples which the Ptolemies raised, rebuilt or substantially enhanced at Philae (Ptolemies II and VIII), Edfu (Ptolemies III, VIII and XII) and Dendera (Ptolemy XII) were based on ancient beliefs and designs, yet are instantly recognisable today, even to the non-expert, as Ptolemaic. Their walls are decorated with an increasing amount of hieroglyphic text, almost as if the priests realised the need to preserve their heritage in stone. It is ironic that these, Egypt’s atypical but best-surviving temples, heavily influenced by contemporary Hellenistic architectural thought, have to be used to reconstruct the rituals conducted in Egypt’s ‘purer’ and now vanished dynastic temples.

Their obvious interest in the native gods earned the Ptolemies valuable propaganda points and encouraged national stability. Thebes was far less likely to rebel if the influential priests were happy with their lot. But this was not necessarily their primary consideration. The Ptolemies ran Egypt outside Alexandria as a profitable business and their decision to invest in the temples was a part of their wider decision to keep the traditional bureaucracy functioning. For many centuries the cult temples of the state gods had played an important role in Egypt’s redistributive economy. The system was a simple but effective one. The crown both generated its own income (farming its own lands, operating mines, quarries and workshops, etc.) and

collected taxes and rents in both coin and kind. This income was used to pay the crown’s expenses, and any surpluses were stored in the large warehouses within the local palace complexes, where they offered a shield against future bad harvests. Part of the royal income was used to provide offerings to the local temples. Here the god, in the form of a statue, lived in the sanctuary. He was served by priests who cared for him as they might care for a child: he was roused in the mornings, washed, dressed, fed, entertained, fed again and put to bed at night.

The temple, the house of the god, was the one place where the mortal could communicate with the divine, but this communication could be achieved only via the king and his deputies. It was, in theory, the king and the king alone who supplied the god with regular offerings of food, drink, clothing, incense and recitations. The god was capable of accepting or rejecting these offerings, but he could not physically consume anything. His leavings were therefore redistributed among the temple staff (essentially, they paid the temple staff), with any surpluses being stored in the temple warehouses, which also housed the revenue from the temple’s assets. These assets, for a prosperous temple, might include land, peasants, mines, workshops and ships which, distributed throughout Egypt, were either owned outright or leased from the crown. The temple priests administered and accounted for these assets and the gods paid tax on their income and duty on the goods that they manufactured in their workshops. An investment in Egypt’s temples was therefore a thinly disguised investment in the Egyptian economy and it comes as little surprise to find Ptolemies VIII and XII, kings whose reigns were characterised by uncertainty and civil unrest, donating generously to the traditional gods. Cleopatra lacked the time and resources to be the great temple builder that her father had been. However, as well as completing her father’s work at Edfu and Dendera, she built the now-demolished birth house in the Armant temple of Montu, and the barque or boat shrine of Geb at Koptos. She

also, as we noted in

Chapter 2

(pages 42–3), showed an interest in Egypt’s bull cults.

The dynastic Egyptians had embalmed a wide range of animals (including fish, mice, snakes, crocodiles and bulls) prior to burial in dedicated animal cemeteries. However, during the Late and Graeco-Roman periods, at a time when the traditional Egyptian culture was threatened by foreign influences, interest in the animal cults blossomed. Diodorus Siculus tells the story of one Roman unfortunate, lynched for inadvertently offending against Graeco-Egyptian superstition: