Complete Works of Emile Zola (1085 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

Authors: Émile Zola

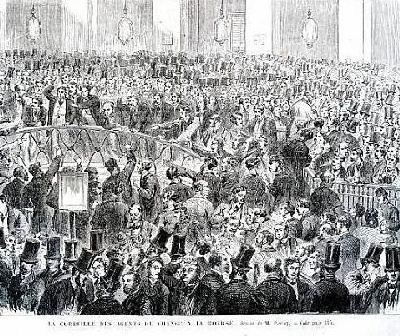

The Bourse, Paris stock exchange, in 1867 — the setting of the novel

The Bourse today

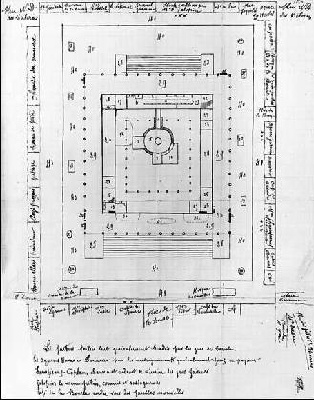

Plan of the Bourse drawn by Zola in his research

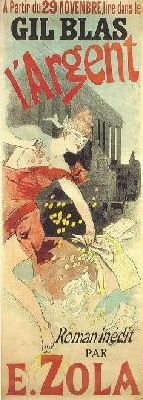

A publicity poster of the novel

CONTENTS

CHAPTER XII

The German actress Brigitte Helm, who starred in the film version of 1929

Poster for the 1936 film version

PREFACE

The present version of M. Zola’s novel ‘L’Argent’ supplies one of the missing links in the English translations of the Rougon-Macquart series which the author initiated some five and twenty years ago, and brought to a close last summer by the publication of ‘Doctor Pascal.’ Judged by the standard of popularity, ‘L’Argent’ may be said to rank among M. Zola’s notable achievements, for not only has it had an extremely large sale in the original French, but the translations of it into various Continental languages have proved remarkably successful. This is not surprising, as the book deals with a subject of great interest to every civilized community. And with regard to this English version, it may, I think, be safely said that its publication is well timed, for the rottenness of our financial world has become such a crying scandal, and the inefficiency of our company laws has been so fully demonstrated, that the absolute urgency of reform can no longer be denied.

A work, therefore, which exposes the evils of ‘speculation,’ which shows the company promoter on the war-path, and the ‘guinea-pig’ basking at his ease, which demonstrates how the public is fooled and ruined by the brigands of Finance, is evidently a work for the times, even though it deal with the Paris Bourse instead of with the London market. For the ways of the speculator, the promoter, the wrecker, the defaulter, the reptile journalist, and the victim, are much the same all the world over; and it matters little whence the example may be drawn, the warning will apply with as much force in England as in France.

The time for prating of the purity of our public life, and for thanking the Divinity that in financial as in other matters we are not as other men, has gone by. When disasters like that of the Liberator group are possible, when examples of financial unsoundness are matters of everyday occurrence, when the very name of ‘trust company’ opens up visions of incapacity, deceit, and fraud, it is quite certain that things are ripe for stringent inquiry and reform.

Of course the cleansing of the Augean stable of finance in this country will prove a Herculean labour; but although callous Governments and legislators may postpone and shirk it, the task remains before them, ever threatening, ever calling for attention, and each day’s delay in dealing with it only adds to the evil. We are overrun with rotten limited liability companies, flooded with swindling ‘bucket-shops,’ crashes and collapses rain upon us, and the ‘promoter’ and the ‘guinea-pig’ still and ever enjoy impunity. It is becoming more and more impossible to burke the issue. It stares us in the face. Even if the various measures of political and social reform, about which we have heard so much of recent years, should yield all that their partisans declare they will, it is doubtful whether there would be much national improvement. For the rottenness of our social system must still remain the same; the fabric must still repose upon as unsound a basis as it does now if the brigands of Finance remain free to plunder the community and to pave their way to ephemeral wealth and splendour with the bodies of the thrifty and the credulous.

One may well ask why this freedom should be allowed them. The man in the street who wishes to lay odds against the favourite for the Derby is promptly mulcted in pocket or consigned to limbo, but the promoter of the swindling company, and the keeper of the swindling ‘bucket-shop,’ who deliberately defraud other people of their money, are at liberty to ply their nefarious callings with no worse fate before them than a short suspension of their discharge should they choose to close their books with the aid of the Bankruptcy Court. There cannot be two moralities, although a distinguished Frenchman, the late M. Nisard, once tried to demonstrate that there were, and was laughed to scorn for his pains. We know that there is but one true morality — the same for the rich as for the poor, the same for the legislator as for the elector, the same for the defaulter who dabbles in millions as for the welsher who sneaks half-crowns. And it should be borne in mind that the harm done to the community at large by the thousands of bookmakers disseminated throughout the United Kingdom is as nothing beside that which is done by the half thousand financial brigands who infest the one city of London. It may, I think, be safely said that more people were absolutely ruined by the crash of the Liberator group than by all the betting on English racecourses over a period of many years.

There have been, I believe, over 2,200 applicants for relief to the fund which has been raised for the benefit of the sufferers of so-called Philanthropic Finance, and among the number it appears there are nearly 1,400 single women and widows. Some of the victims have committed suicide, others have gone mad. Thousands, moreover, who are too proud to beg, find themselves either starving or in sadly straitened circumstances, with nothing but a pittance left them of their former little comforts. This is a specimen of the work done by the brigand of Finance.

Of course there are reforms urgently needed in the very organisation of the Stock Exchange; and reforms needed with regard to the conditions under which public companies may be launched. Why should men be allowed to ask the public to subscribe millions of money for the purchase of properties which are literally valueless? Why, moreover, should directors be allowed to proceed to ‘allotment,’ when but a tithe of the shares placed on the market have been taken up? And surely the time has come for the proper auditing of accounts under Government supervision. The neglectful auditor and the fraudulent promoter are as much in need of abolition as the ornamental ‘guinea-pig.’ And such abolition, and the enforcement of many reforms, might be secured by a self-supporting Ministry of Commercial Finance. Some institution of the kind will doubtless be founded in time to come; and, meanwhile, if all that is told us of the purity of our public life be true, I fail to see why a series of measures directed against the brigands of Finance should not promptly receive the assent of both Houses of Parliament and become law. Surely no member of the Lords or the Commons would dare to stand up and plead the cause of the negligent director who imperils the safety of other people’s money? Surely not one of our legislators would dare to take the fraudulent promoter and the rogue of the ‘bucket-shop’ under his protecting wing? And, as such measures must of necessity be non-contentious, why do not some of our social reformers initiate them, instead of for ever and ever harping upon ‘Bills’ which are not likely to be included in the Statute-book for another score of years?

I am not against public companies. Let us have them; let us have as many good ones as we can get, but let them be honestly founded and honestly administered. It is through the multiplicity of public companies that we may eventually attain to Collectivism, which so many great thinkers of the age deem to be the future towards which the world is slowly but surely marching. And when that comes, perhaps, as Sigismond Busch, one of M. Zola’s characters, foreshadows in the following pages, we shall have some other means of exchange than money — the metallic money of the present day. Sigismond Busch is a Karl Marxite, a believer in the universal fraternity of humanity, a fraternity which he regretfully admits is still far away from us. Of a very different stamp to him is M. Zola’s hero — if hero he can be called — Saccard, the scheming financier, the sanguine promoter and manager of the Universal Bank, the poet of money, the apostle of gambling, ever intent on gigantic enterprises, believing that the passion for gain should be fostered rather than discouraged, and that in order to set society on a proper basis it is necessary to destroy the financial power of the Jews.