Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (117 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

[A summer day. Far up in the North. A hut in the forest. The door, with a large wooden bar, stands open.

Reindeer-horns over it. A flock of goats by the wall of the hut.]

[A MIDDLE-AGED WOMAN, fair-haired and comely, sits spinning outside in the sunshine.]

THE WOMAN

[glances down the path, and sings]

Maybe both the winter and spring will pass by,

and the next summer too, and the whole of the year; —

but thou wilt come one day, that know I full well;

and I will await thee, as I promised of old.

[Calls the goats, and sings again.]

God strengthen thee, whereso thou goest in the world!

God gladden thee, if at his footstool thou stand!

Here will I await thee till thou comest again;

and if thou wait up yonder, then there we’ll meet, my friend!

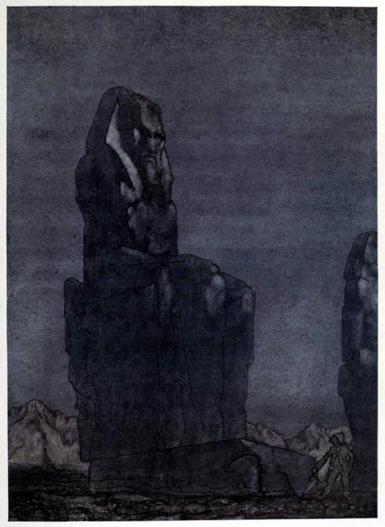

[In Egypt. Daybreak. MEMNON’S STATUE amid the sands.]

[PEER GYNT enters on foot, and looks around him for a while.]

PEER GYNT

Here I might fittingly start on my wanderings. —

So now, for a change, I’ve become an Egyptian;

but Egyptian on the basis of the Gyntish I.

To Assyria next I will bend my steps.

To begin right back at the world’s creation

would lead to nought but bewilderment.

I will go round about all the Bible history;

its secular traces I’ll always be coming on;

and to look, as the saying goes, into its seams,

lies entirely outside both my plan and my powers.

[Sits upon a stone.]

Now I will rest me, and patiently wait

till the statue has sung its habitual dawn-song.

When breakfast is over, I’ll climb up the pyramid;

if I’ve time, I’ll look through its interior afterwards.

Then I’ll go round the head of the Red Sea by land;

perhaps I may hit on King Potiphar’s grave. —

Next I’ll turn Asiatic. In Babylon I’ll seek for

the far-renowned harlots and hanging gardens, —

that’s to say, the chief traces of civilisation.

Then at one bound to the ramparts of Troy.

From Troy there’s a fareway by sea direct

across to the glorious ancient Athens; —

there on the spot will I, stone by stone,

survey the Pass that Leonidas guarded.

I will get up the works of the better philosophers,

find the prison where Socrates suffered, a martyr — ;

oh no, by-the-bye-there’s a war there at present — !

Well then, my Hellenism must even stand over.

[Looks at his watch.]

It’s really too bad, such an age as it takes

for the sun to rise. I am pressed for time.

Well then, from Troy — it was there I left off —

[Rises and listens.]

What is that strange sort of murmur that’s rushing — ?

[Sunrise.]

Peer and the Statue of Memnon

MEMNON’S STATUE

[sings]

From the demigod’s ashes there soar,

youth-renewing,

birds ever singing.

Zeus the Omniscient

shaped them contending

Owls of wisdom,

my birds, where do they slumber?

Thou must die if thou rede not

the song’s enigma!

PEER

How strange now, — I really fancied there came

from the statue a sound. Music, this, of the Past.

I heard the stone — accents now rising, now sinking. —

I will register it, for the learned to ponder.

[Notes in his pocket-book.]

“The statue did sing. I heard the sound plainly,

but didn’t quite follow the text of the song.

The whole thing, of course, was hallucination. —

Nothing else of importance observed to-day.”

[Proceeds on his way.]

[Near the village of Gizeh. The great SPHINX carved out of the rock. In the distance the spires and minarets of Cairo.]

[PEER GYNT enters; he examines the SPHINX attentively, now through his eyeglass, now through his hollowed hand.]

PEER GYNT

Now, where in the world have I met before

something half forgotten that’s like this hobgoblin?

For met it I have, in the north or the south.

Was it a person? And, if so, who?

That Memnon, it afterwards crossed my mind,

was like the Old Men of the Dovre, so called,

just as he sat there, stiff and stark,

planted on end on the stumps of pillars. —

But this most curious mongrel here,

this changeling, a lion and woman in one, —

does he come to me, too, from a fairy-tale,

or from a remembrance of something real?

From a fairy-tale? Ho, I remember the fellow!

Why, of course it’s the Boyg, that I smote on the skull, —

that is, I dreamt it, — I lay in fever. —

[Going closer.]

The self-same eyes, and the self-same lips; —

not quite so lumpish; a little more cunning;

but the same, for the rest, in all essentials. —

Ay, so that’s it, Boyg; so you’re like a lion

when one sees you from behind and meets you in the daytime!

Are you still good at riddling? Come, let us try.

Now we shall see if you answer as last time!

[Calls out towards the SPHINX.]

Hei, Boyg, who are you?

A VOICE

[behind the SPHINX]

Ach, Sphinx, wer bist du?

PEER

What! Echo answers in German! How strange!

THE VOICE

Wer bist du?

PEER

It speaks it quite fluently too!

That observation is new, and my own.

[Notes in his book.]

“Echo in German. Dialect, Berlin.”

[BEGRIFFENFELDT COMES OUT from behind the SPHINX.]

BEGRIFFENFELDT

A man!

PEER

Oh, then it was he that was chattering.

[Notes again.]

“Arrived in the sequel at other results.”

BEGRIFFENFELDT

[with all sorts of restless antics]

Excuse me, mein Herr — ! Eine Lebensfrage — !

What brings you to this place precisely to-day?

PEER

A visit. I’m greeting a friend of my youth.

BEGRIFFENFELDT

What? The Sphinx — ?

PEER

[nods]

Yes, I knew him in days gone by.

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Famos! — And that after such a night!

My temples are hammering as though they would burst!

You know him, man! Answer! Say on! Can you tell

what he is?

PEER

What he is? Yes, that’s easy enough.

He’s himself.

BEGRIFFENFELDT

[with a bound]

Ha, the riddle of life lightened forth

in a flash to my vision! — It’s certain he is himself?

PEER

Yes, he says so, at any rate.

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Himself! Revolution! thine hour is at hand!

[Takes off his hat.]

Your name, pray, mein Herr?

PEER

I was christened Peer Gynt.

BEGRIFFENFELDT

[in rapt admiration]

Peer Gynt! Allegoric! I might have foreseen it. —

Peer Gynt? That must clearly imply: The Unknown, —

the Comer whose coming was foretold to me —

PEER

What, really? And now you are here to meet — ?

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Peer Gynt! Profound! Enigmatic! Incisive!

Each word, as it were, an abysmal lesson!

What are you?

PEER

[modestly]

I’ve always endeavoured to be

myself. For the rest, here’s my passport, you see.

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Again that mysterious word at the bottom.

[Seizes him by the wrist.]

To Cairo! The Interpreters’ Kaiser is found!

PEER

Kaiser?

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Come on!

PEER

Am I really known — ?

BEGRIFFENFELDT

[dragging him away]

The Interpreters’ Kaiser — on the basis of Self!

[In Cairo. A large courtyard, surrounded by high walls and buildings. Barred windows; iron cages.]

[THREE KEEPERS in the courtyard. A FOURTH comes in.]

THE NEW-COMER

Schafmann, say, where’s the director gone?

A KEEPER

He drove out this morning some time before dawn.

THE FIRST

I think something must have occurred to annoy him;

for last night —

ANOTHER

Hush, be quiet; he’s there at the door!

[BEGRIFFENFELDT leads PEER GYNT in, locks the gate, and puts the key in his pocket.]

PEER

[to himself]

Indeed an exceedingly gifted man;

almost all that he says is beyond comprehension.

[Looks around.]

So this is the Club of the Savants, eh?

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Here you will find them, every man jack of them; —

the group of Interpreters threescore and ten;

it’s been lately increased by a hundred and sixty —

[Shouts to the KEEPERS.]

Mikkel, Schlingelberg, Schafmann, Fuchs, —

into the cages with you at once!

THE KEEPERS

We!

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Who else, pray? Get in, get in!

When the world twirls around, we must twirl with it too.

[Forces them into a cage.]

He’s arrived this morning, the mighty Peer; —

the rest you can guess, — I need say no more.

[Locks the cage door, and throws the key into a well.]

PEER

But, my dear Herr Doctor and Director, pray — ?

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Neither one nor the other! I was before —

Herr Peer, are you secret? I must ease my heart —

PEER

[with increasing uneasiness]

What is it?

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Promise you will not tremble.

PEER

I will do my best, but —

BEGRIFFENFELDT

[draws him into a corner, and whispers]

The Absolute Reason departed this life at eleven last night.

PEER

God help me — !

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Why, yes, it’s extremely deplorable.

And as I’m placed, you see, it is doubly unpleasant;

for this institution has passed up to now

for what’s called a madhouse.

PEER

A madhouse, ha!

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Not now, understand!

PEER

[softly, pale with fear]

Now I see what the place is!

And the man is mad; — and there’s none that knows it!

[Tries to steal away.]

BEGRIFFENFELDT

[following him]

However, I hope you don’t misunderstand me?

When I said he was dead, I was talking stuff.

He’s beside himself. Started clean out of his skin, —

just like my compatriot Munchausen’s fox.

PEER

Excuse me a moment —

BEGRIFFENFELDT

[holding him back]

I meant like an eel; —

it was not like a fox. A needle through his eye; —

and he writhed on the wall —

PEER

Where can rescue be found!

BEGRIFFENFELDT

A snick round his neck, and whip! out of his skin!

PEER

He’s raving! He’s utterly out of his wits!

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Now it’s patent, and can’t be dissimulated,

that this from-himself-going must have for result

a complete revolution by sea and land.

The persons one hitherto reckoned as mad,

you see, became normal last night at eleven,

accordant with Reason in its newest phase.

And more, if the matter be rightly regarded,

it’s patent that, at the aforementioned hour,

the sane folks, so called, began forthwith to rave.

PEER

You mentioned the hour, sir, my time is but scant —

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Your time, did you say? There you jog my remembrance!

[Opens a door and calls out.]

Come forth all! The time that shall be is proclaimed!

Reason is dead and gone; long live Peer Gynt!

PEER

Now, my dear good fellow — !

[The LUNATICS come one by one, and at intervals, into the courtyard.]

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Good morning! Come forth,

and hail the dawn of emancipation!

Your Kaiser has come to you!

PEER

Kaiser?

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Of course!

PEER

But the honour’s so great, so entirely excessive —

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Oh, do not let any false modesty sway you

at an hour such as this.

PEER

But at least give me time — !

No, indeed, I’m not fit; I’m completely dumbfounded!

BEGRIFFENFELDT

A man who has fathomed the Sphinx’s meaning!

A man who’s himself!

PEER

Ay, but that’s just the rub.

It’s true that in everything I am myself;

but here the point is, if I follow your meaning,

to be, so to phrase it, outside oneself.

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Outside? No, there you are strangely mistaken!

It’s here, sir, that one is oneself with a vengeance;

oneself, and nothing whatever besides.

We go, full sail, as our very selves.

Each one shuts himself up in the barrel of self,

in the self-fermentation he dives to the bottom, —

with the self-bung he seals it hermetically,

and seasons the staves in the well of self.

No one has tears for the other’s woes;

no one has mind for the other’s ideas.

We’re our very selves, both in thought and tone,

ourselves to the spring-board’s uttermost verge, —

and so, if a Kaiser’s to fill the throne,

it is clear that you are the very man.

PEER

O would that the devil — !

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Come, don’t be cast down;

almost all things in nature are new at the first.

“Oneself;” — come, here you shall see an example;

I’ll choose you at random the first man that comes

[To a gloomy figure.]

Good-day, Huhu! Well, my boy, wandering round

for ever with misery’s impress upon you?

HUHU

Can I help it, when the people,

race by race, dies untranslated?

[To PEER GYNT.]

You’re a stranger; will you listen?

PEER

[bowing]

Oh, by all means!

HUHU

Lend your ear then. —

Eastward far, like brow-borne garlands,

lie the Malabarish seaboards.

Hollanders and Portugueses

compass all the land with culture.

There, moreover, swarms are dwelling

of the pure-bred Malabaris.

These have muddled up the language,

they now lord it in the country. —

But in long-departed ages

there the orang-outang was ruler.

He, the forest’s lord and master,

freely fought and snarled in freedom.

As the hand of nature shaped him,

just so grinned he, just so gaped he.

He could shriek unreprehended;

he was ruler in his kingdom. —

Ah, but then the foreign yoke came,

marred the forest-tongue primeval.

Twice two hundred years of darkness

brooded o’er the race of monkeys;

and, you know, nights so protracted

bring a people to a standstill. —

Mute are now the wood-notes primal;

grunts and growls are heard no longer; —

if we’d utter our ideas,

it must be by means of language.

What constraint on all and sundry!

Hollanders and Portugueses,

half-caste race and Malabaris,

all alike must suffer by it. —

I have tried to fight the battle

of our real, primal wood-speech, —

tried to bring to life its carcass, —

proved the people’s right of shrieking, —

shrieked myself, and shown the need of

shrieks in poems for the people. —

Scantly, though, my work is valued. —

Now I think you grasp my sorrow.

Thanks for lending me a hearing; —

have you counsel, let me hear it!

PEER

[softly]

It is written: Best be howling

with the wolves that are about you.

[Aloud.]

Friend, if I remember rightly,

there are bushes in Morocco,

where orang-outangs in plenty

live with neither bard nor spokesman; —

their speech sounded Malabarish; —

it was classical and pleasing.

Why don’t you, like other worthies,

emigrate to serve your country?

HUHU

Thanks for lending me a hearing; —

I will do as you advise me.

[With a large gesture.]

East! thou hast disowned thy singer!

West! thou hast orang-outangs still!

[Goes.]

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Well, was he himself? I should rather think

so.

He’s filled with his own affairs, simply and solely.

He’s himself in all that comes out of him, —

himself, just because he’s beside himself.

Come here! Now I’ll show you another one,

who’s no less, since last evening, accordant with Reason.

[To a FELLAH, with a mummy on his back.]

King Apis, how goes it, my mighty lord?

THE FELLAH

[wildly, to PEER GYNT]

Am I King Apis?

PEER

[getting behind the DOCTOR]

I’m sorry to say

I’m not quite at home in the situation;

but I certainly gather, to judge by your tone —

THE FELLAH

Now you too are lying.

BEGRIFFENFELDT

Your Highness should state

how the whole matter stands.

THE FELLAH

Yes, I’ll tell him my tale.

[Turns to PEER GYNT.]

Do you see whom I bear on my shoulders?

His name was King Apis of old.

Now he goes by the title of mummy,

and withal he’s completely dead.

All the pyramids yonder he builded,

and hewed out the mighty Sphinx,

and fought, as the Doctor puts it,

with the Turks, both to rechts and links.

And therefore the whole of Egypt

exalted him as a god,

and set up his image in temples,

in the outward shape of a bull. —

But I am this very King Apis,

I see that as clear as day;

and if you don’t understand it,

you shall understand it soon.

King Apis, you see, was out hunting,

and got off his horse awhile,

and withdrew himself unattended

to a part of my ancestor’s land.

But the field that King Apis manured

has nourished me with its corn,

and if further proofs are demanded,

know, I have invisible horns.

Now, isn’t it most accursed

that no one will own my might!

By birth I am Apis of Egypt,

but a fellah in other men’s sight.

Can you tell me what course to follow? —

then counsel me honestly. —

The problem is how to make me

resemble King Apis the Great.

PEER

Build pyramids then, your highness,

and carve out a greater Sphinx,

and fight, as the Doctor puts it,

with the Turks, both to rechts and links.

THE FELLAH

Ay, that is all mighty fine talking!

A fellah! A hungry louse!

I, who scarcely can keep my hovel

clear even of rats and mice.

Quick, man, — think of something better,

that’ll make me both great and safe,

and further, exactly like to

King Apis that’s on my back!

PEER

What if your highness hanged you,

and then, in the lap of earth,

‘twixt the coffin’s natural frontiers,

kept still and completely dead.

THE FELLAH

I’ll do it! My life for a halter!

To the gallows with hide and hair! —

At first there will be some difference,

but that time will smooth away.

[Goes off and prepares to hang himself.]

BEGRIFFENFELDT

There’s a personality for you, Herr Peer, —

a man of method —

PEER

Yes, yes; I see — ;

but he’ll really hang himself! God grant us grace!

I’ll be ill; — I can scarcely command my thoughts!

BEGRIFFENFELDT

A state of transition; it won’t last long.

PEER

Transition? To what? With your leave — I must go —

BEGRIFFENFELDT

[holding him]

Are you crazy?

PEER

Not yet — . Crazy? Heaven forbid!

[A commotion. The Minister HUSSEIN forces his way through the crowd.]

HUSSEIN

They tell me a Kaiser has come to-day.

[To PEER GYNT.]

It is you?

PEER

[in desperation]

Yes, that is a settled thing!

HUSSEIN

Good. — Then no doubt there are notes to be answered?

PEER

[tearing his hair]

Come on! Right you are, sir; — the madder the better!

HUSSEIN

Will you do me the honour of taking a dip?

[Bowing deeply.]

I am a pen.

PEER

[bowing still deeper]

Why then I am quite clearly

a rubbishy piece of imperial parchment.

HUSSEIN

My story, my lord, is concisely this:

they take me for a sand-box, and I am a pen.