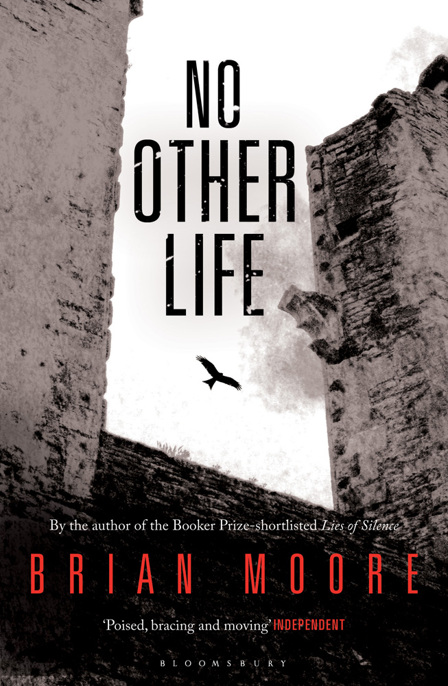

No Other Life

Authors: Brian Moore

NO OTHER LIFE

BRIAN MOORE

God moves the player, he, in turn, the piece.

But what god beyond God begins the round

of dust and time and dream and agonies?

– Jorge Luis Borges

For Jean

Contents

In the old days they would have given me a gold watch. I never understood why. Was it to remind the one who is being retired that his time is past? Instead of a watch I have been presented with a videotape of the ceremonies. My life here has ended. My day is done.

Next week I will leave Ganae and fly to a retreat house in Cuba. I have never lived in Cuba. Canada, where I was born and bred, is only a memory. You might ask why I was not permitted to end my days here. I am one of the last white priests on this island and the last foreign principal of the Collège St Jean. At the ceremonies on Tuesday night, this was not mentioned. But yesterday, alone in the sitting room of our residence, watching the videotape which they have made for me, I saw myself as they must now see me. The ceremony was held in the college auditorium. Priests, nuns, students and dignitaries, all were mulatto or black. On the wall behind the microphones and the podium there was a large photograph of our new Pope, himself a man of mixed blood. And then, walking towards the podium, a ghost from the past, this stooped white man in a frayed cassock, incongruous as the blackamoor attendant in a sixteenth-century painting of the French court. I am a reminder of a past they feel is best forgotten. They are happy to see me go.

And yet, on the videotape, they weep, they embrace me. Some profess love for me. One of my former students, now the Minister for Foreign Affairs, praised me in his address for my efforts to bring the benefits of higher education to scholarship students from city slums and rural backwaters. There was applause when he said it, but how many in his audience thought of Jeannot at that moment? Jeannot, the most important milestone of my life, is nowhere mentioned in this farewell ceremony. On the video screen, surrounded by smiling faces, I cut slices from a large cake. The videotape, like the gold watch of other days, attests that I lived and worked with these people for most of my adult life. It is a memento.

But what sort of memento? I am a member of the Albanesians, a Catholic teaching Order, founded in France. Unlike lay people who retire, I have no family, no children, or grandchildren, no link with normal life. My brother and my sister are strangers I have not seen for many years. When a religious retires it is as though he is struck down with a fatal illness. His earthly task is over. Now he must prepare himself for death. In another age it was a time of serenity, of waiting to be joined with God and those who have gone before. But, for me, death is a mystery, the answer to that question which has consumed my life.

At the ceremonies last Tuesday, our boys’ choir sang the school song. The words were composed by Father Ricard, a French priest who was principal here before my time. It is a sort of hymn in which God is asked to bless our school and, through education, to bring wealth and happiness to Ganae and its people. Father Pinget makes mock of this song saying that, evidently, God does not speak French.

French, of course, is out of favour now. When I came here it was the opposite. Creole was the language of the poor. To speak French was to show that one belonged, or aspired to belong, to the mulatto elite. Now, Creole is the official tongue. But does God speak Creole?

I think of these things because I am looking at the empty pages of my life. My years here have counted for little. I have failed in most of the things that I set out to do. But I am a man with a secret, with a story never told. Even now, as I write it down, is it the moment to tell the truth?

Where should I begin? Shall I begin with the anxiety that came upon me last night as I removed from the walls of my room the photograph of my parents and a second photograph showing my graduating class, long ago, at the University of Montreal? I put them in the trunk that contains my belongings, the same flat tin trunk which was carried up to this room when I first arrived in Ganae, thirty years ago. Next week, when they carry that trunk downstairs, there will be no sign that I ever lived here. I think it is that – the knowledge that the truth of these events may never be known – that makes me want to leave this record.

But how should I tell it? When we are young we assume that, in age, we will be able to look back and remember our lives. But just as we forget the details of a story a few months after hearing it, so do the years hang like old clothes, forgotten in the wardrobe of our minds. Did I wear that? Who was I then?

That is a question I cannot answer. I can tell you that my name is Paul Michel and that I was born sixty-five years ago in the town of Ville de la Baie in Northern Quebec. My father was a doctor in that town and when he died my younger brother, Henri, took over the practice. Why did

I

not become a doctor? I do not remember that, as a child, I was especially devout. I was educated by the Albanesian Fathers at their college in Montreal and when I showed some glimmerings of literary talent the Order offered me a chance to do graduate work at McGill University and, later, sent me for a year to read French literature at the Sorbonne. Now, looking back, I do not know if I had a true vocation for the priesthood. I was attracted to the Order by its propaganda about devoting one’s life to teaching the poor in faraway places. I became an Albanesian Father much as others of my generation were to join the Peace Corps.

The priesthood meant celibacy and that, for me, caused a terrible confusion. I would feel hopeless longings for a girl seen in the street, followed by a depression which my prayers could not cure. In Paris, I fell in love. She was a fellow student at the Sorbonne. On her part, it was innocent. I was just a friend. I thought for a time of giving up the priesthood and asking her . . . but I did nothing. It was not until I was posted to Ganae that my longing for her was eased. Here, far from any world I had known, I would live my life as God’s servant, doing His work.

I was soon disappointed. I had come to teach the poor. Ganae is in the Caribbean, but is as poor as any African country. Eighty per cent of the population is illiterate. The few state schools are pathetically inefficient. The state university is an inferior training college which turns out substandard doctors and engineers. Our school, the Collège St Jean in Port Riche, is the only private institution of higher education. It was founded to produce students who could gain admission to foreign universities when they completed their high-school studies and went abroad. For this reason it was, from the beginning, a school for the sons of the mulatto elite, an elite who lived in large estates behind high walls and security gates, waited on by black servants, an elite who aped French manners, served champagne and

haute cuisine

, and gossiped about the new couture collections and the latest Parisian

scandale

. When I began to teach at the Collège St Jean, we had fewer than twenty black students in our classrooms.

Why was this so? Our Principal, Father Bourque, explained it this way. ‘The mulattos run Ganae, they always have. They control the parliament, they have business ties with the US and France. By educating their children we have a chance to influence events. This is a black republic but the shade of black is all important. Light skins rule. When a

noir

becomes successful he tries to marry into the

mulâtre

class. Besides, our Archbishop is a conservative. He wants to maintain the status quo.’

What would I have done if things had not held out some hope of change? Would I have become disillusioned and pragmatic like Father Bourque? Luckily, I was not put to the test. A few months after my arrival, in one of those political shifts not unknown in Ganae, a black country dentist named Jean-Marie Doumergue ran for election, promising to abolish torture, promote democracy, and curb the powers of the police. The Army saw in Doumergue a puppet they could use to control the black masses. Doumergue was elected. But, at once, he began to attack the privileges of the mulatto elite.

Why do we remember certain mornings, certain meetings? I can still recall my anxiety on that morning when I stood outside our Principal’s office with eight black boys clustered around me. The Archbishop had just arrived. Our Principal opened his office door and beckoned me to bring the boys inside. I bowed humbly to Archbishop Le Moyne, a cold Breton whom I did not know. He and the Principal went on talking as though the boys were not in the room.

‘We are dealing with a new situation,’ Father Bourque said. ‘We now have a president who repeats constantly that he has a mandate to improve the education of his fellow

noirs

, a president who complains about schools like ours. There are no other schools like ours. He is talking about our school. And so, Your Grace, if you will bear with me, I would like to propose that we increase the number of our scholarship pupils immediately. I am thinking of a sizeable number of scholarships. Perhaps forty. And they should all be

noirs

.’

But the Archbishop did not agree. ‘I’m afraid the elite will not tolerate their children mixing with children of the slums. A few more

noirs

, yes. The elite does not wish to seem bigoted, especially with a

noir

in power. But forty black students – where would you find them?’

Our Principal turned to me. ‘Father Michel has been doing some groundwork in that regard. Father?’

I was holding a sheaf of test results. I was, as always in those days, nervous and overanxious. ‘Your Grace,’ I said, ‘I have been travelling around the rural districts, and, believe me, I have had no trouble finding

noir

children of higher than average intelligence. Here are eight of them. For example, this little fellow seems quite exceptional. And yet he is an orphan, from the poorest of the poor – the village of Toumalie, if that means anything to Your Grace?’

As I was speaking I kept an eye on the boys. The other seven stood humbly, like animals whose sale was in the balance. But the one I had singled out, the boy named Jeannot, stared at us as though he, not we, were deciding his future. And then, suddenly, this boy said, ‘I wish to be a priest, Your Grace. No one from Toumalie has ever been a priest.’

Afterwards, at lunch, the Archbishop asked, ‘Surely you are not planning to make priests out of these little

noirs

? The college is not a seminary.’

Our Principal laughed. ‘The boy from Toumalie? I don’t know why he said that. Probably to make us take him in. Do you know, Paul?’

I suppose Father Bourque was merely trying to bring me into the conversation. I had sat tongue-tied throughout the meal. But, because I desperately wanted to have the boys accepted by the school, I answered with an evasion.

‘I have no idea,’ I said. ‘I hardly know the boy.’