Complete Works of Jane Austen (2 page)

Read Complete Works of Jane Austen Online

Authors: Jane Austen

The plot centres on the Dashwood sisters and their romantic suitors, Edward Ferrars, John Willoughby and Colonel Brandon. The novel begins with Mrs Dashwood and her three daughters being removed from their home after Mr Dashwood dies and the property is left to his son John from his first marriage. Fanny, John’s wife, a cold, calculating woman, has a brother Edward, who comes to stay with the family and develops a rapport with Elinor, before they are separated by circumstances. Meanwhile, Marianne meets the charming and dashing Willoughby and enters into a passionate relationship with him.

An interesting facet of the novel is Austen’s assessment of Marianne’s nature and behaviour, which she renders more sympathetically than might have been the case. The author originally began composing the work during the aftermath of the French Revolution; a period of great anxiety in England at the possibility of social upheaval. During this period, novels centred on heroes of great sensibility were fashionable and widespread; most importantly they were viewed as potentially socially and politically subversive. Excessive sensibility was linked by the ruling class to the bloody and violent French Revolution, where they a perceived there was a loss of reason and control. One conservative reaction to this anxiety was to criticise and satirise this emphasis on feeling and subjective experience and portray them as dangerous and threatening. Though Austen clearly exposes what she believes to be the hazards of unrestrained emotion, she portrays Marianne in a largely attractive and sympathetic light. Conversely, Elinor’s extreme reserve and emotional inhibitions are shown to cause her much pain and anguish.

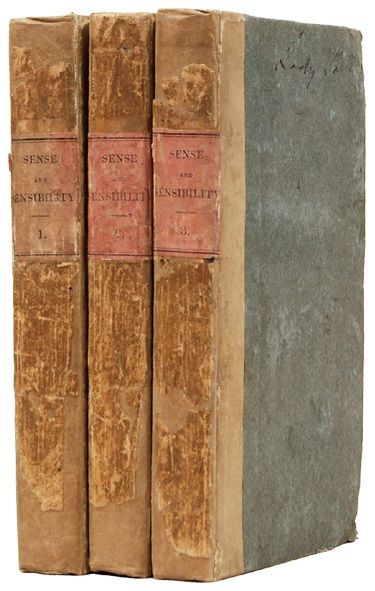

The first edition

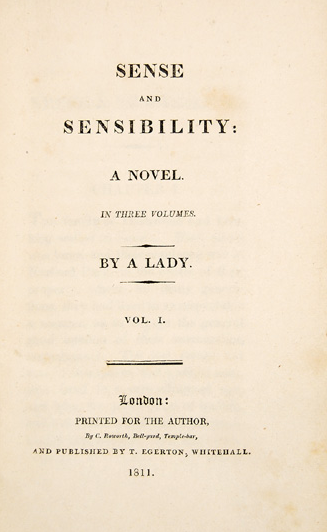

The original title page

CONTENTS

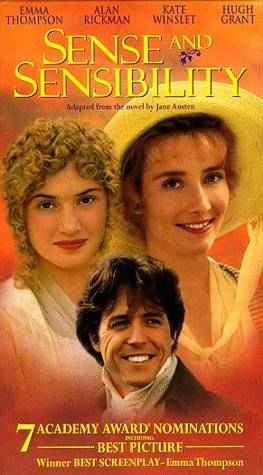

The Oscar winning 1995 film adaptation

Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet in the 1995 adaptation

The 2008 television adaptation

INTRODUCTION

With the title of

Sense and Sensibility

is connected one of those minor problems which delight the cummin-splitters of criticism. In the

Cecilia

of Madame D’Arblay — the forerunner, if not the model, of Miss Austen — is a sentence which at first sight suggests some relationship to the name of the book which, in the present series, inaugurated Miss Austen’s novels. ‘The whole of this unfortunate business’ — says a certain didactic Dr. Lyster, talking in capitals, towards the end of volume three of

Cecilia

—’has been the result of Pride and Prejudice,’ and looking to the admitted familiarity of Miss Austen with Madame D’Arblay’s work, it has been concluded that Miss Austen borrowed from

Cecilia

, the title of her second novel. But here comes in the little problem to which we have referred.

Pride and Prejudice

it is true, was written and finished before

Sense and Sensibility

— its original title for several years being

First Impressions

. Then, in 1797, the author fell to work upon an older essay in letters

à la

Richardson, called

Elinor and Marianne

, which she re-christened

Sense and Sensibility.

This, as we know, was her first published book; and whatever may be the connection between the title of

Pride and Prejudice

and the passage in

Cecilia

, there is an obvious connection between the title of

Pride and Prejudice

and the

title of Sense and Sensibility

. If Miss Austen re-christened

Elinor and Marianne

before she changed the title of

First Impressions

, as she well may have, it is extremely unlikely that the name of

Pride and Prejudice

has anything to do with

Cecilia

(which, besides, had been published at least twenty years before). Upon the whole, therefore, it is most likely that the passage in Madame D’Arblay is a mere coincidence; and that in

Sense and Sensibility

, as well as in the novel that succeeded it in publication, Miss Austen, after the fashion of the old morality plays, simply substituted the leading characteristics of her principal personages for their names. Indeed, in

Sense and Sensibility

the sense of Elinor, and the sensibility (or rather

sensiblerie

) of Marianne, are markedly emphasised in the opening pages of the book But Miss Austen subsequently, and, as we think, wisely, discarded in her remaining efforts the cheap attraction of an alliterative title.

Emma

and

Persuasion, Northanger Abbey

and

Mansfield Park

, are names far more in consonance with the quiet tone of her easy and unobtrusive art.

Elinor and Marianne

was originally written about 1792. After the completion — or partial completion, for it was again revised in 1811 — of

First Impressions

(subsequently

Pride and Prejudice

), Miss Austen set about recasting

Elinor and Marianne

, then composed in the form of letters; and she had no sooner accomplished this task, than she began

Northanger Abbey

. It would be interesting to know to what extent she remodelled

Sense and Sensibility

in 1797-98, for we are told that previous to its publication in 1811 she again devoted a considerable time to its preparation for the press, and it is clear that this does not mean the correction of proofs alone, but also a preliminary revision of MS. Especially would it be interesting if we could ascertain whether any of its more finished passages,

e.g.

the admirable conversation between the Miss Dashwoods and Willoughby in chapter x., were the result of those fallow and apparently barren years at Bath and Southampton, or whether they were already part of the second version of 1797-98. But upon this matter the records are mute. A careful examination of the correspondence published by Lord Brabourne in 1884 only reveals two definite references to

Sense and Sensibility

and these are absolutely unfruitful in suggestion. In April 1811 she speaks of having corrected two sheets of ‘S and S,’ which she has scarcely a hope of getting out in the following June; and in September, an extract from the diary of another member of the family indirectly discloses the fact that the book had by that time been published. This extract is a brief reference to a letter which had been received from Cassandra Austen, begging her correspondent not to mention that Aunt Jane wrote

Sense and Sensibility.

Beyond these minute items of information, and the statement — already referred to in the Introduction to

Pride and Prejudice

— that she considered herself overpaid for the labour she had bestowed upon it, absolutely nothing seems to have been preserved by her descendants respecting her first printed effort. In the absence of particulars some of her critics have fallen to speculate upon the reason which made her select it, and not

Pride and Prejudice

, for her début; and they have, perhaps naturally, found in the fact a fresh confirmation of that traditional blindness of authors to their own best work, which is one of the commonplaces of literary history. But this is to premise that she

did

regard it as her masterpiece, a fact which, apart from this accident of priority of issue, is, as far as we are aware, nowhere asserted. A simpler solution is probably that, of the three novels she had written or sketched by 1811,

Pride and Prejudice

was languishing under the stigma of having been refused by one bookseller without the formality of inspection, while

Northanger Abbey

was lying

perdu

in another bookseller’s drawer at Bath. In these circumstances it is intelligible that she should turn to

Sense and Sensibility

, when, at length — upon the occasion of a visit to her brother in London in the spring of 1811 — Mr. T. Egerton of the ‘Military Library,’ Whitehall, dawned upon the horizon as a practicable publisher.