Confessions of a Public Speaker (13 page)

Read Confessions of a Public Speaker Online

Authors: Scott Berkun

Tags: #BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Skills

If you ask people not to use cell phones, and someone answers a

call in the front row, what should you do? It’s up to you to enforce the

house

rules because you have the microphone. Or what about the

guy who asks a question that goes on for three whole minutes? How long

will you let him ramble on? Twenty seconds is more than enough time for

a question; after 40 seconds, it’s a monologue and everyone in the

audience hates him. But after a minute, people will be staring at you.

You are allowing all of the energy to be sucked out of the room. They

can’t do much about it, but they know you can.

Never be afraid to enforce the rules you know the room wants you

to follow. When in doubt, ask the room for a show of hands: “Should we

continue with this topic or move on?” If they vote to move on, that’s

what you should do. When you enforce a popular rule, you reengage

everyone who supports that rule. You restore your power and earn the

audience’s respect. So, don’t hesitate to cut off a blowhard, silence

the guy on his cell phone, and interrupt the table having a private but

distracting conversation. As long as you are polite and direct, you’ll

be a hero.

People want to leave early, but when those same people get the

microphone, they run late. Don’t be like them. Always plan and practice

to end early. If a window of opportunity presents itself to finish a few

minutes ahead of schedule—giving your audience a head start on beating

traffic, getting to their next meeting, or attacking the snacks in the

conference hall—do it. No one ever wants you to go longer. If people

really love you, they’ll often stick around to hear more of what you

have to say. Let everyone else escape. Give the audience your email

address, and stress that you’ll happily answer additional questions over

email. Be as generous and giving of your time as you like, but make sure

people are opting in, not being forced to listen to you more. Be an

attention liberator and set them free. Case in point: this chapter is

over.

It’s May of 2008, and I’m at

CNBC studios dressed in black shoes, black pants, and a

black turtleneck, staring into a camera surrounded by bright white lights.

Looking into a wall of lights seems like heaven until you realize that you

can’t see anything, your eyes hurt, and it’s fucking hot. With each

passing second, it’s less clear whether the goal is to film me or to see

how long it takes for me to melt like the witch from

The Wizard

of Oz

. Perhaps it’s both. On the ground is a strip of masking

tape that marks where my feet need to stay as the 10-person film crew

surrounds me with various gear, cameras, light filters, and microphones,

ensuring I look fantastic as I embarrass myself on national television.

Despite how hard it is to stand still for so long, the real challenge is

that I’m expected to do the worst kind of nothing—the kind of nothing

where I have no distractions while everyone stares, prods, and pokes me—as

I wait and wait for them to be ready for me to say my lines. To stop my

mind from exploding due to the sheer helplessness of being trapped in

permanent hurry-up-and-wait mode, I focus on the drama playing out every

few minutes behind the crew, drama only I can see.

It goes like this: CNBC employees come into the café to get a bite

to eat but stop mid-stride, surprised at the site of me in their fancy

cafeteria, clad in all black, illuminated by a sea of lights like the

leader of the scary aliens in a sci-fi movie. Saddened by the discovery

that their lunchroom has been converted into an enormous glowing

soundstage, they glare at me for a long moment before turning back to the

halls to search for other provisions. They glare with the same disdain

you’d have for the asshole who smiles as he steals your parking space. I

want to tell them it’s not my fault. I want to point at the crew so they

share the blame, but there is no escape. I am clearly the target of their

hate for the rest of the afternoon. Standing alone on the set, an entire

crew orbiting around me, it must appear as though I think I’m the center

of the universe, a concept which—given the many layers of embarrassment

running through my mind—could not be further from the truth.

I’m at CNBC to film a five-hour primetime TV series called

The Business of Innovation

(

Figure 7-1

). It’s a media

jackpot for an independent like me, so I’m trying as hard as possible not

to screw it up. But in these moments on the first day of taping, dressed

like a Steve Jobs impersonator (at CNBC’s request), I’m feeling 10%

adrenalin, 20% fear of embarrassment, and 70% complete and utter panic.

There are too many contradictions for me to hold on to sanity. First, I

have no idea what is going on, yet I’m the center of attention, much like

how it would feel to be invited over for dinner by a family of cannibals.

Second, I’m a star of the show, yet I have no control and no shortage of

people telling me what to do. Third, I’m fascinated by everything and want

to ask hundreds of questions but can’t because I’m surrounded by busy film

professionals who have little patience for my curiosity. Even if I were a

narcissist, even if I loved seeing myself on film (which I don’t), it

would be impossible not to panic and think I’ve made a big and permanent

mistake—after all, bloopers last forever on YouTube. If they post any of

my flubs online, including the take where my fly was open, it will be more

famous than anything else I ever do.

Figure 7-1. The B-roll footage for The Business of Innovation. Notice the

chair in the background, a chair no one ever sat in.

The good news for me is that I’m only one of five experts for the

series, and I know I can hide behind the others at any time. We make quite

a crew: Vijay Vaitheeswaran writes for the

Economist

, Keith Yamashita runs his own innovation

consulting firm, Ranjay Gulati teaches at Harvard University, and Suzy

Welch writes for

Business Week

. Headlining the show

is Maria Bartiromo, the star anchor for

CNBC (even cooler, she’s the only woman in history to have a

tribute song written to her by Joey Ramone). And on top of this, each

hour-long episode is packed with a rock-star list of CEOs, politicians,

luminaries, and venture capitalists, including Jack Welch (former CEO of

GE), Howard Schultz (CEO of Starbucks), Marc Ecko (fashion mogul), and

Muhammad Yunis (Nobel Peace Prize recipient in 2006).

The impressive lineup continues with the CEOs of Zappos,

Kodak, LG, Xerox, FedEx, and Sirius Radio, as well as executives from

Harley-Davidson, Timberland, Procter & Gamble, and on it goes. But for

all the massive power of these featured guests, you’d be most surprised by

one thing: they were just as afraid of being on television as I

was.

Despite their entourages, fame, and ridiculous levels of success and

media exposure, nearly everyone seemed just as disoriented by television

as I was. No one talked about this, of course. It’s like being bored at a

funeral—most are, but no one wants to admit it first. But I saw their

jittery hands, heard their nervous questions, and sat in many long,

awkward, tense silences with these very famous people. There was regular

caffeine and sugar abuse, and the green room

[

35

]

was packed with an arsenal of such provisions. The producers

know that many people shut down from nerves and shrink to whispers when on

camera, as some of these executives did on the show. So, the producers err

on the side of a caffeine-and-sugar-induced fistfight with a co-host than

sedate mumbles and soft shrugs.

To assuage their fears, many high-powered executives travel with

staff, media experts, or heads of PR. These folks follow their clients

around on the set, mediating discussions, approving decisions, and

whispering private advice to them. It doesn’t seem to help; in fact, the

people who bring PR staff with them are the ones who probably have more to

be worried about. Herb Kelleher (founder of Southwest Airlines) and Jack

Welch were all on their own, and the friendliest and funniest people I

talked with on the show.

The real killer in all this, the thing no PR or flunky can

compensate for, is the waiting. Many people can work themselves into the

right mindset to do fine on television, but there is so much hurrying up

to wait that it’s hard to time the mindset with the opportunity to use it.

You get ready, you get psyched, and then uh oh,

another reason to wait 10 minutes. It’s shocking for CEOs

and luminaries to learn their time is not as valuable to the network as it

is to their companies. They will be forced to arrive early, wait around,

and wait some more as needed to serve the making of the show.

What few understand is that the world of TV has its own place in the

space–time continuum—every second matters more to them than to the rest of

the working world. Despite the power of the Web, it’s TV that still has

the most money at stake per second of product. Case in point: based on my

bestseller

The Myths of Innovation

,

CNBC flew me across the country to interview me to appear as

an expert on the show. The interview lasted exactly 33 minutes. So for 10

hours of flight and travel time for me to get to NYC, I spent less than an

hour interviewing to appear on a TV show. They covered my costs and hotel,

as they would throughout filming, but it was always clear: I was working

for them, not the other way around. For the true star guests of the show,

those with entourages or their own private islands, it must have been

baffling to rearrange their busy executive travel schedules, fly across

the country, drive all afternoon in traffic to get to CNBC, and wait for

hours in a studio just to be filmed for exactly 4 minutes and 30 seconds

(of which, perhaps half is used on air in the final edit). It was likely

the most humbling

experience they had all year. They shared the same look of

disbelief when, on set, they were told, “That’s a wrap, great job!”, just

when they felt they were getting warmed up. They expected to have the same

star power as in the rest of their lives, forgetting to realize that in

the world of TV, they are just another cog in the machine.

Speaking of making the show, the wall of lights I’m standing in

front of in

Figure 7-1

is

for taping what’s called

B-roll

. When I ask what the

B-roll is, I’m told it’s everything that’s not the A-roll. Asking a rookie

question gets you a sardonic answer; sarcasm and jargon reign in the

stressful world of television. TV people seem bright and upbeat but also

high-strung and impatient. Nothing happens fast enough for them. I’d later

learn that the

A-roll

is the primary footage for the

show, whereas the B-roll is the intros, credits, and other secondary

footage. When you are watching TV, B-roll is what appears during the

credits or between commercials, the bits of footage you never think about.

It’s easy to forget that someone produces every single second of

television. When you see Dr. House (from his eponymous show) on TV, even

if just for a commercial advertising the program, it means a crew spent

hours setting up the lights. If you hear him speak, it means sound

engineers spent hours setting up microphones and mixing sound. There is an

expensive back story to every split-second of broadcast media, as every

choice costs money and is done for specific reasons. And if they do it

right, you never even think about it.

Have you ever been in a bar as brightly lit as the one on

Cheers

? Or a hospital as cheery as on

Scrubs

? We know television isn’t real, but if done

right, the consistent lack of reality creates its own immersive world.

They call this

suspension of disbelief

. Even for

nonfiction shows like

The Business of Innovation

or

The Daily Show with Jon Stewart

, what you see is

never actually what happened during taping. There is editing. There is

sound mixing. Camera lenses change how people look. There are hundreds of

deliberate choices made for specific reasons, which explains why the

B-roll is filmed in the cafeteria and not the studio. They want it to look

very different from the A-roll, and with $200,000 worth of lights, gear,

backdrops, and effects, the cafeteria looks instead like a conference room

on the

Starship Enterprise

. You’d never guess where

we shot it if I hadn’t told you, even if you worked at

CNBC. The viewers will never know how silly it felt to stand

there in the cafeteria, how many takes it took for me to get each line

right, or how ridiculous the whole thing was during filming. And even

watching the B-roll myself, it was hard to connect what I

experienced with what was actually televised.

The big lesson from being on television is simple: we are always

performing. Any time you open your mouth and expect

someone to listen, you are behaving differently than you would if you

were alone. Admitting this doesn’t make you a phony—it makes you honest.

We are social creatures and behave differently to fit into different

social situations. Here’s an example. Think of a funny story or joke you

know well.

[

36

]

Now imagine telling that joke three different

times:

To your best friend on your couch

To five friends over dinner at a restaurant

To 20 of your coworkers in a boardroom

In each

case you are

performing to achieve an effect, primarily to make your

audience laugh. Each situation might be different, so the way you tell

the joke will change. The same is true every time you open your mouth to

speak. You always have a goal, whether it’s to express a thought, ask a

question, or make an observation. In trying to achieve that goal you

are, in a sense, performing. And the bigger the audience, the bigger you

need to be. Your voice needs to be louder, your hand gestures more

dramatic, and your pace more upbeat. This is especially true for

television. Since your appearance might be on a tiny TV in someone’s

living room or in a browser window on his computer, you have to act big

to project yourself across that distance.

Having done most forms of public speaking, I’ve learned that

television, radio interviews, YouTube videos, high school theater,

podcasts, and monologues are simply different kinds of performances.

Some are more intense than others, like being on national television, or

require more practice and rehearsal, like acting in a stage play, but

the basic rules are the same. Most people say they’re afraid of

performing for an audience, but this is bullshit. Unless you are living

alone on a private island and have your groceries mailed to you, you

have an audience every time you open your mouth. If you can talk to your

mom on the phone for an hour or have an all-night fight with your

boyfriend, you know most of what you need to communicate. And you

already know how to perform. You know how to express anger, fear,

passion, joy, and confusion. You know how to be dramatic, how to attract

attention, and most importantly, how to convert what you’re thinking

into words that you say and actions you do. It’s just a question of

doing it at the right level for the environment you’re in.

[

37

]

Oprah, Conan O’Brien, and Katie Couric know how to talk to

the camera

as if they were talking to a friend. It’s their ability to

make the strange, awkward world of

broadcast seem normal—even comfortable—that explains why

viewers like watching them. Howard Stern talks to his audience as if he

were having beers with his buddies, which is why people tend to love him

or hate him. Success often stems from the ability to make whatever

medium you’re in feel like something simpler and often less formal. It’s

the art of making the unnatural seem natural.

Few people think of television or radio as public speaking, which

is strange when you run the numbers. By definition, being broadcast

means that you will be seen by way more people than anything you

normally do. The first time I was on TV was in 1997 on a small cable

show,

CNET TV

; my appearance lasted a total of 180

seconds. It was entirely miserable, embarrassing, and paralyzing. I had

no coaching and only limited media exposure. Whatever that experience

was, it certainly did not feel like speaking, as I mostly mumbled and

tried to get my hands to stop shaking. I remember how weird it felt to

wear makeup (everyone on TV wears makeup), and how absurd it was to have

a half-dozen bright lights aimed right at my face. I remember thinking:

how do they expect me to see, much less say anything?

Being on television or radio, where millions of people will get to

see and/or hear you, requires speaking in a studio devoid of an

audience. Instead of a crowd of people, there is a circle of lights and

producers. Instead of interested, friendly faces, there are cold,

lifeless cameras and large, shiny microphones. When you watch the

nightly news, you see Brian Williams or Katie Couric behind a nice desk,

on an interesting-looking stage with a smart background. It’s all sharp,

classy, new, and put together with care. But anything not visible on

camera, which is the majority of the room Katie or Brian sits in,

probably looks like the engine room of a Navy battleship.

There are tall black walls, exposed ductwork, electronics, and

gear everywhere. The fancy graphics you see over their shoulders or the

tickers scrolling across the bottom of your TV do not exist anywhere in

the studio. In their place is empty space reserved for those digital

additions. On the studio floor in front of Katie, or in my case, Maria

Bartiromo, engineers scurry about in headsets and talk in whispers.

There are places where you’re warned not to step, and long stretches of

time when you cannot make a sound. There are no windows. There are no

plants. There is nothing comfortable or friendly about it. Simply put, a

TV studio is an expensive machine for making TV shows. Everything works

in service of the mythical audience, but that audience is not present.

TV studios are flat-out

unpleasant, unfriendly environments, more like factory

floors or scientific laboratories than comfy, supportive, warm places.

Even though all the producers and production assistants were fun, smart,

and attentive, they can’t overcome the relentless pace of the process.

The set at CNBC for

The Business of Innovation

had the additional challenge of being mostly virtual, except for the

platform and couch. We shot against a blue screen with the entire set

filled in digitally later (see the before and after in Figures

Figure 7-2

and

Figure 7-3

). Does that couch

look comfortable to you?

Figure 7-2. The set at CNBC for The Business of Innovation.

It’s true that many stages and auditoriums aren’t friendly either,

but by contrast to a TV studio, I can always see or hear what’s going

on—who’s listening, who’s bored. My senses work to my advantage. And if

I happen to say something completely stupid and inappropriate, like

perhaps forget where I am and claim how great it is to be in Boston when

I’m actually lecturing somewhere in NYC, I know instantly how the crowd

feels about what I said, even if it’s only their desire to kill me. I

always have the chance to respond to how the audience is responding to

me. But there is no audience feedback in most TV studios. This means you

might say exactly what the audience hoped, perhaps the secrets to

instant weight loss or how to achieve immediate world domination (or

peace, if you’re a sissy), but you would get no real-time reaction.

Alternatively, it means you can lie, talk too much, talk too little, be

an idiot, or be brilliant, and have very little sense of what it is you

are actually being.

Figure 7-3. The set as seen on broadcast. That’s me in the middle in the

white shirt.

The lesson I learned from this is that any time you are videotaped

or recorded live without an audience, whether it’s for TV or the Web,

it’s far worse being in an empty room than a tough room. This is why

some shows have live audiences. They want to give their guests the many

advantages of having the support and energy of real people. But most TV

studios don’t have audiences. So, if you’ve ever wondered why people on

TV seem phony, stiff, irritable, or unnatural, it’s in part because

there’s no natural feedback loop for their behavior. On many news shows,

the only company is in the form of talking heads on satellite, people in

similarly isolated environments thousands of miles away.

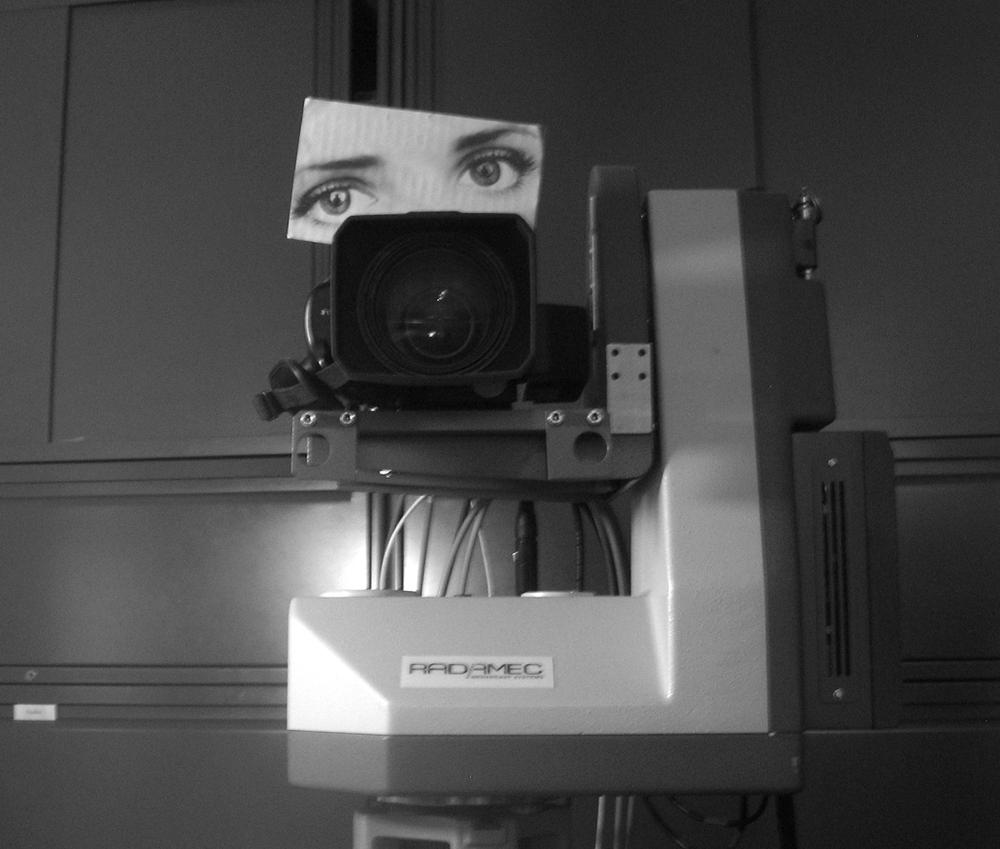

Once when I was on MSNBC via satellite from Seattle, I had my

first chance to be a talking head. Whenever you see someone interviewed

on the news and put in a little virtual box on the screen, in reality

they’re talking from inside a small studio near wherever they happen to

be (

Figure 7-4

). To help

viewers sort this out, they put a cardboard poster with the skyline of

wherever they are up behind them to help clue you in. You never get to

see what these studios look like, in part, because they’re not

interesting (thus the cardboard backdrop). Speaking from within one is

worse than the challenges of the main studio since I can’t even see the

people I’m supposed to be speaking to. You’re just stuck in a small room

that’s

as charming as a large janitor’s closet, with a camera

pointed at your face.

[

38

]

Unless the show I’m on pays a few extra bucks for a live

feed, I can’t even see the video of what’s being taped. All I get is an

earpiece where a producer I’ve never met and can’t see mostly tells me

to wait, while I stare blankly into the lights. I’ve learned there’s a

special kind of anxiety when you’re waiting alone in a room but know

that at any moment you’ll be broadcast across the country.

Figure 7-4. What you see when you’re a talking head.

The secret to speaking to an audience without one actually present

is to forget the studio and ignore the

cameras (

Figure 7-5

). Go to a place in

your mind where you remember the last time you spoke to a live,

friendly, interested group, and match that style of behavior and

enthusiasm. Speak as if that same audience is listening, and you’ll be

fine. Great hosts help you do this by feeding you energy and support, or

even a softball question or two. All performers have a mindset they use

when everything else is going wrong, and that’s what gets them through.

Much like in public speaking, I learned from my experience filming at

CNBC that I just had to switch off the worried part of my brain and

laugh at how bizarre it all was. I bought the ticket by coming on the

show—I should get as much as I can from taking the ride.

Figure 7-5. As creepy as this looks, it helps. Having something to look at

other than the Terminator-like glare of the camera lens is a good

trick to help you seem more comfortable.