Confessions of a Public Speaker (15 page)

Read Confessions of a Public Speaker Online

Authors: Scott Berkun

Tags: #BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Skills

[

39

]

To be fair, the moment when someone leaves the stage is a bad

time to say anything because it is likely that he’s too distracted to

hear what you say.

[

40

]

Naftulin, Donald H., John E. Ware, Jr., and Frank A. Donnelly,

“The Doctor

Fox Lecture: A Paradigm of Educational Seduction,”

Journal of Medical Education

, Vol. 48 (1973):

630–635.

[

41

]

Basic complaints about the study include: the sample size is

small, the video of the lecture cannot be found, and the survey

questions aren’t extensive. However, the study has been reproduced

successfully and is generally supported by other researchers in the

field. See

What’s the Use of Lectures?

,

Donald A. Bligh (Jossey-Bass), p. 202.

[

42

]

One of my most popular essays ever is “How to detect

bullshit”:

http://www.scottberkun.com/essays/53-how-to-detect-bullshit/

.

Most organizers never bother to collect feedback from the

attendees, and

of those who do,

often it doesn’t get passed on to the speakers. It’s a

shame because it’s most appropriate for the organizers to share feedback

with the speakers; after all, they invited them to speak, so technically

the speakers work for the hosts. But being as busy as they are, the

organizers don’t always communicate the gathered data back to the

speakers. They ask the good speakers to come back and leave the rest to

figure out life for themselves.

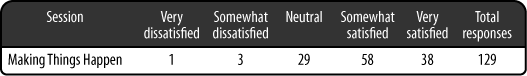

Some do provide feedback, and

Figure 8-1

shows a typical

report for a speaker at an event. This is real data from a real event,

and the speaker was me.

Figure 8-1. My scorecard from a recent speaking engagement.

At first glance, this looks good. Apparently 58 of the 129 people

who responded were “Somewhat satisfied.” That doesn’t sound too bad. I

even managed to score a “Very satisfied” from 38 additional people. But

a rating of “Neutral” from 29 people is worthless. I’d rather they were

forced to decide—if they’re not sure where they stand, I’d consider them

dissatisfied. Or perhaps they dozed

off. That would actually be fascinating data to know: how

many people fell asleep during the lecture? (That’s a stat I’d love to

see at all lectures, especially in universities.)

But the single most valuable data point is how my scores compare

to other speakers. Without it, this feedback is useless. Perhaps my

scores are the worst

of all scores in the history of presentations at this

organization. Or perhaps they’re the best. There is no way to know. And

what about the one guy who was very dissatisfied? Was he important?

Maybe he’s the VP of the division so his opinion matters more than the

others. Or is he, like my former boss, always dissatisfied by

everything? Maybe he has never given a score other than “Very

dissatisfied.” Or perhaps he showed up in the wrong room and thought I’d

be speaking about his favorite topic, which to his dismay I never

mentioned. Reading this report keeps me mostly in the dark.

The most useful feedback conveys what the dissatisfied people wish

I had done differently, and what the satisfied people want me to make

sure I do next time. Even if all 129 said they were beyond very

dissatisfied, and unanimously agreed on a law banning me from ever

speaking again, I wouldn’t know what it was that dissatisfied them. I’d

have to guess at what changes to make to do better next time, once my

appeal goes through and I’m put on speaking probation.

And then, of course, since there were 500 people in the room, what

did the other 371 think about my talk? I’ll never know. Because only a

minority of attendees fill out speaker surveys, the responses typically

represent the top and bottom of the feedback curve. Those who

passionately love or hate you are best represented because they’re the

most motivated to participate. The moderate majority is least

represented. Since surveys are black holes—no one is informed who

exactly will read them, and how they affect the future—there’s little

reason for most people to be thoughtful about what they say.

[

43

]

Without a wise, patient hand reviewing the data, it’s easy to

misinterpret what it means or how the speaker could have possibly done a

better job. Most

of the time, the questions in the survey are framed wrong,

setting up misinterpretations no matter who gives feedback.

Here’s some

of the real feedback speakers need:

How did my presentation compare to the others?

What one change would have most improved my

presentation?What questions did you expect me to answer that went

unanswered?What annoyances did I let get in the way of giving you what

you needed?

No matter what data is provided to a speaker, it’s easy and free

to simply ask people in the audience when you see them afterward. When

someone gives you a polite, “Great job!”, say, “Thanks, but how could I

have made it better?” Get them to move beyond pleasantries and think for

a moment. Give them your business card to encourage them to continue the

discussion. After the event, ask your host the aforementioned questions

and see what data he’ll share with you. Even if he doesn’t have data

from the audience, he can give his own opinions, which can be just as

valuable.

[

43

]

I ran training events at Microsoft for years, and promised

that I would personally read every answer submitted in surveys. If

people aren’t sure who will read their feedback, why would they

spend 5 or 10 thoughtful minutes giving it? They won’t. Perhaps the

surveys will go straight to the trash; who knows? If you don’t make

someone accountable and visible, you’re encouraging people to be

cynical of surveys and they will not take them seriously, if they do

them at all.

What would happen if, in 1942, I booked Mussolini to speak in

London? Mussolini was a passionate, perhaps excellent, speaker. But what

do you think his survey results would look like? Instead of evaluating

Mussolini, the only thing the survey scores would indicate is that the

organizer failed to match the speaker to the audience. Speakers can be

set up to fail if they are asked to speak to people who hate them, or on

a topic they do not care about. I spoke once at Cooper Union, an elite,

world-famous university in New York City, where all admitted students

get full scholarships. I was on a book tour promoting one of my books.

The talk I’d prepared was about all the things that go wrong on projects

and how a wise leader can handle them. It was good material, and I’d

presented it well many times. But when I arrived, I learned my audience

was made up entirely of freshmen: 18- and 19-year-olds without any

real-world adult experience. It was October, so they’d been out

of high school for maybe five months. I knew instantly,

minutes before I was to speak, I was Mussolini in London. Unless I did

something drastic, they’d ignore or heckle me as if I were a boring,

out-

of-touch, manager-loser type—the same way I would have if,

at 19, I’d had to sit through a lecture about life in the corporate

world.

A savvy speaker must ask the host, “What effect do you want me to

have on this audience?”, and a good host will think carefully about that

answer. And if he doesn’t, the speaker may very well be able to figure

this out, or interact enough with people in the audience to sort out

what they want to get out of the lecture itself. Most of the time people

are asked to speak, they say yes without knowing why they were asked or

what they are expected to achieve.

During my talk at Cooper Union, I did my best to remember my

perception of the adult world when I was 18. So, I dropped my slides,

opened with a personal story of my experiences working at Microsoft, and

joked about how I met Bill Gates in an elevator (I said hello and he

basically ignored me), which earned some mild laughs. I scored an ounce

of respect and grew it into a lively Q&A that lasted the hour. I was

lucky to pull this off; had I initially asked some basic questions of

the host, I would have been prepared from the beginning.

Sometimes the goal is a deliberate mismatch. The host wants a

challenging presentation that will inform people of opinions they don’t

want to hear to rile them up. That’s fine, provided at least the host

and the speaker are in agreement and whatever survey is done takes this

into consideration. Satisfaction means something very different if the

goal was to provoke rather than merely to please.

This points out the real challenge in evaluating speakers. Whoever

it is that invites someone to speak to an audience has to sort

out:

What they (the organizer) want from the speaker.

What the audience wants from the speaker.

What the speaker is capable of doing.

If these three things are not lined up well, the survey will

always have problems (e.g., Mussolini in London). If they are aligned,

the questions used to evaluate the speaker should be public.

Everyone—the speaker, the audience, and the organizer—should know how

the speaker is going to be evaluated. Then the speaker will know in

advance and can prepare, much like Dr. Fox, to do whatever he can to

score well on those evaluations. Rarely does the audience get a say in

surveys, but they should be helping the organizer form the

questions.

Better questions to ask attendees include:

Was this a good use

of your time?Would you recommend this lecture to others?

Are you considering doing anything different as a result

of this talk?Do you know what to do next to continue learning?

Were you inspired or motivated?

[

44

]How likeable did you find the speaker?

How substantive did you find the speaker’s material?

Those last two questions sort out the Dr. Fox dilemma of how well

liked speakers were versus how much substance attendees felt the speaker

offered them. And if you really want to know the value of a speaker, ask

the students a week or a month later. A lecture that might have seemed

amazing or boring five minutes after it ended could have surprisingly

different value for people later on. If the goal is to change people’s

behavior in the long term, you have to study the long-term impacts of

whatever lectures or courses people are taking.

[

44

]

This may matter more than how much they learned.

As cautious as we are about giving other people tough criticism,

we’re even more terrified of receiving it. However, it’s quite easy

today to get feedback on public speaking. In fact, you can do this right

now:

Grab a video camera.

Open your notes or slides for a talk you know (the Gettysburg

Address works in a pinch).Videotape

yourself presenting it.

Five minutes will do just fine. Imagine you have an audience on

the wall opposite you, who you should be making eye contact with, and go

for it. Then sit down, perhaps with your favorite alcoholic beverage (or

seven), and watch. Despite how easy this is to do, most people, even

those who say public speaking is important and want to get better at it,

aren’t willing to do it. It’s just too scary for them. To which I say,

you are a hypocrite. If you’re too scared to watch

yourself speak, how can you expect your audience to watch

you? The golden rule applies: don’t ask people to listen to something

you haven’t listened to yourself. Just do it. If it’s unwatchable, be

proud you only inflicted a rotten talk on yourself and not an innocent

audience. You can delete the video. You cannot delete an hour of wasted

time from people’s lives.

We all hate the sound of our own voice. We scrutinize the shape of

our nose or our hairline in ways most people never would. Besides, those

are things that are difficult to change. It’s the other things—how

comfortable you seem, how clear your points are, any minor annoyances of

body language or diction—that are radically easier to improve.

If you don’t like what you see, make it shorter. Go for 30

seconds—short, commercial-length material—and practice it until you can

do it well. Then add more. If something feels consistently stupid, take

it out and repeat. You will always get better each time you practice

something, even if it seems otherwise.

I don’t watch video of every talk I do, but if during a talk it

doesn’t feel right, or something goes really well, I’ll go back and

watch. When I get feedback from an event organizer that’s difficult to

interpret, I’ll compare it with the videotape. I always want to match my

sense of how it felt to me to what it actually looked like to the

audience. Pro athletes rely on watching films of their games to see what

actually happened (Fred didn’t play any defense) instead of what they

think happened (Fred blames the rest of his team for not playing any

defense).

[

45

]

There’s too much going on when you’re doing an intense

activity like sports or speaking to be fully aware of what’s happening

as it happens. Use technology to help show you what you actually did. If

you’re intimidated by critiquing yourself, make the video and give it to

a trusted friend who you know will give you honest, constructive

feedback. Keep in mind that a webcam is a tool orators and speakers

throughout history would have loved to have had. It’s simple, fast,

cheap, and private. You can get instant feedback from people nearby or

far away, making it easier than ever to experience what it’s like to be

in your own audience.

[

45

]

“There is only one way to stay on top of it: when you watch it

on films. Only then can the players and coaches see what went wrong.

There are no make-believes with the films, and sometimes it takes a

couple of viewings before it sinks in.”—Chuck Daly, former Detroit

Pistons head coach. Quoted in Ron Hoff’s

I Can See You

Naked

(Andrews McMeel Publishing), where he offers

similar advice.