Confessions of a Public Speaker (6 page)

Read Confessions of a Public Speaker Online

Authors: Scott Berkun

Tags: #BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Skills

Half

of what you pay for at a fancy restaurant isn’t the food.

You’re paying its rent, you’re paying for the atmosphere, and you’re

paying for the way its service makes you feel. If you’ve ever taken a date

somewhere based on where it is, what it looks like, or how it feels to be

there, you know this is true. Public speaking is no different; the

atmosphere is important to the quality of everyone’s experience. If you

had to listen to Martin Luther King, Jr., in a New York City subway

station, or Winston Churchill in a highway rest stop bathroom, with all

the smells, noises, and rodents those atmospheric monstrosities are known

for, you’d be less than pleased. MLK’s most famous speech would go

something like this: “I have a…

eloquence would be no match for the unpleasant and distractive powers of

the environment around him.

Place

matters to a

speaker because it matters to the audience. Old theaters, a university

lecture hall, even the steps of the Lincoln Memorial are great places to

speak, but most speakers rarely get asked to do their thing

in venues this good. Most presentations are given under

flickering fluorescent lights inside cramped conference rooms, or in

convention halls designed with a thousand other functions in mind, which

explains why I know way more than I should about

chandeliers.

While you are in the audience looking up at the stage, a stage

designed to make me easy to see, often I can’t see anything (see

Figure 4-1

). All the house

lights are aimed right at my face. People forget that the room, as bad as

it might be, is set up to help the audience see, whereas we speakers are

on our own. Whenever you see pictures of a famous person giving a famous

lecture, you see the stage exactly the way the person with the best seat

in the house saw it. No one else is on stage, and if someone is, he’s not

moving around. If President Obama were giving a speech and a dozen people

behind him were eating cheeseburgers or playing charades, everyone in the

audience would be quite annoyed. But when I look out into the audience,

all I see are distractions. I can see and hear the back doors opening and

closing with every person arriving late or leaving early. I see the glow

of laptops in people’s multitasking eyes. I see cameramen and stage crews

moving heavy gear, flashing their lights, and making jokes, all in the

back rows behind the crowd, where only I can see. And most

depressing of all, on some days, the days I forget to make a

sacrifice to the gods of public speaking, all I can see when I look

straight ahead is the dizzying glare of the conference hall chandelier.

These are the cheap ones, made of grey metal, covered in chipping, peeling

gold paint. They hover in the space above the crowd, a place where few in

the audience ever look, but precisely where a speaker’s eyes naturally

want to go. In a good room, the ceiling is free of distractions; in a bad

room, there’s a large glowing ball of stupidity hanging there.

Figure 4-1. At a big event with stage lights. This gives an idea of what I

see: mostly nothing.

Disco balls work because they’re undeniably silly and make fun of

real attempts at decoration, but

chandeliers, even the cheap ones I often see, are entirely

serious. Despite their phony plastic flame-shaped light bulbs (who was

ever fooled by these?), they are a lame attempt to give a room class, a

kind of class that—to the disappointment of the owners of these

rooms—cannot be obtained by hanging something large and shiny from the

ceiling. I’m told these chandeliers are placed in conference halls for one

reason: weddings. They want to rent the room out for weddings—the highest

marked-up events in the Western world—and somehow without an ugly

chandelier in the brochure, they fear they’ll never be chosen as a wedding

venue again. Next time you’re at a lecture, check the ceiling. If you spot

a chandelier, know that it’s not there for you.

Why pick on a glorified light fixture? Why risk being

banned from speaking at chandelier-industry conferences for

the rest of my life? Here’s why. Presenters talk about “tough rooms” all

the time, usually referring to the audience. They blame the crowd when

they should first blame the

room

. Many challenges are created by

the room itself, challenges of atmosphere that change lukewarm crowds into

tough ones. Ever try to throw a birthday party in a graveyard or a funeral

in an amusement park? Of course not. You’d be set up to fail—unless your

family has handfuls of Xanex for breakfast or you’re related to Tim

Burton. Most venues for speaking and lecturing in the modern world are

dull, grey, uninspiring, poorly lit, generic cubes of space. They are

designed to be boring (which is why it’s hard to stay awake during

lectures) so they can be used for anything. And like a Swiss Army knife,

this means they suck at everything. Your average conference room or

corporate lecture hall is bought and sold for its ability to serve many

different purposes, though none of them well, which explains my unnatural,

and possibly deadly, level of exposure to

chandeliers. Blame speakers all you want—we do deserve most

of the blame—but some fraction of hate should go to whoever chose the

crappy room to stick the audience in. It’s not my choice. If I had my

choice, here’s where you’d see me (check out

Figure 4-2

).

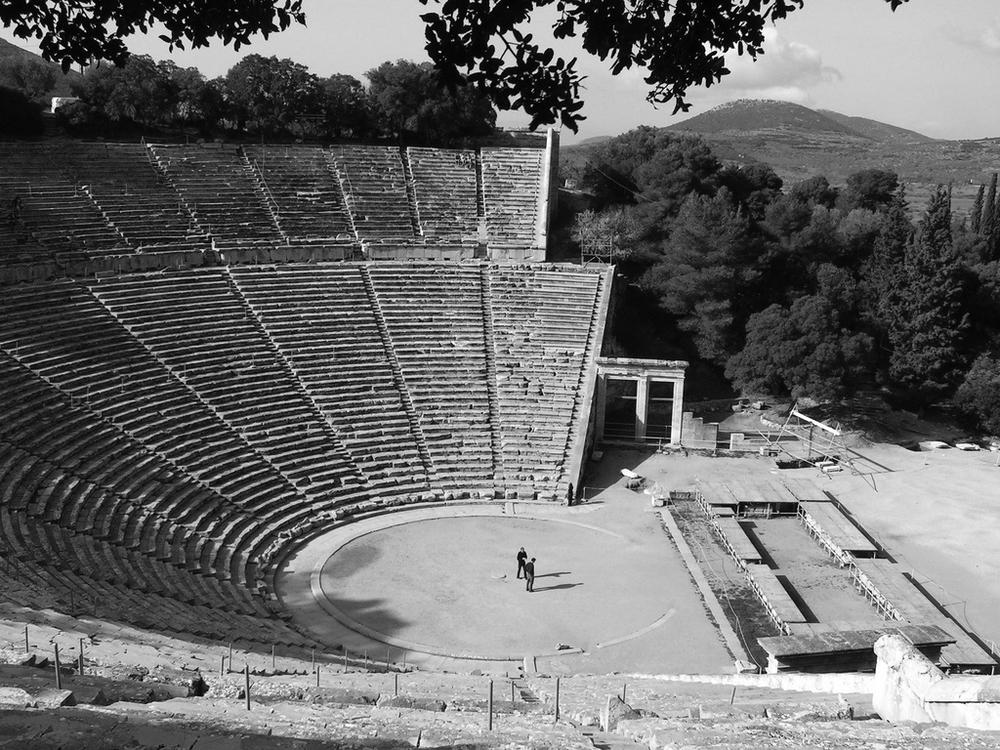

Figure 4-2. The Greek Theater at Epidaurus.

I’d want to be at this Greek amphitheater, in part, because I hear

it’s quite nice in Greece, but mostly because the

ideal room for a lecture is a theater. It’s crazy, I know,

but we solved most lecture-room problems about 2,000 years ago. The Greek

amphitheater gets it all just about right, provided it doesn’t rain.

Lecture rooms should be a semicircle, not a square. The stage should be a

few feet higher than the front row, both to make people on the stage

e

asier to see, but also to help them feel powerful. And most

importantly, every row of seats should be higher off the ground than the

one before it, giving everyone a clear line of sight. All of these things

make it easier for the audience to stay interested and focus its attention

on center stage, as well as provide the speaker with natural

acoustics.

One of the best lectures I’ve given in recent memory was at Carnegie

Mellon University in the Adamson Wing, a theater-sized room that seats

maybe 120 (see

Figure 4-3

).

[

22

]

If you put a kegerator inside the lectern and added a

remote-controlled shock system that would electrify individual seats on

command (an anti-heckler device), it would be perfect.

Figure 4-3. The Adamson Wing at Carnegie Mellon University, a room designed

well for lectures.

And, of course, the most overlooked advantage of Greek-style

amphitheaters and good university lecture halls? No

chandeliers.

Theaters are rare. They cost more to build and to rent, and few

conference centers have them. When they do, they’re often reserved for the

big-name speakers on the schedule. Everyone else gets the square, dingy,

poorly lit loser

rooms. I speak in loser rooms all the time. But if you’re

invited to give a lecture and get a choice of rooms,

ask for the one that’s most theater-like. Even if it’s

smaller, even if it’s farther away, the room will score you extra points.

I get giddy all over when I know I’m speaking in a room set up to help me

connect

with the audience. A room free of poles and blind spots, a

room with good lighting, a room that’s soundproofed well enough so we

don’t hear the traffic outside or the lecture next door. It’s rare, but

when it happens, the people who hire me get their money’s worth.

In a square room, there are many

problems few talk about. If you’re in an aisle seat at the

far right or left of the room, staring straight ahead, you’ll be looking

at the front wall. To see what’s going on, you have to turn your head or

your body toward the center of the front. You also have to try and look

over or between the heads of the people in front of you—which if you’re

more than 20 rows back can be impossible. If you can’t see the speaker,

why are you there? You might as well watch the lecture on TV in the bar,

so you can play lecture drinking games with your friends, such as

“ummmster,” where you do a shot of your favorite cocktail every time the

speaker says “ummm.” With some speakers, you’ll be passed out in no

time.

If you’re in the audience, the angle of your body and the amount of

eye contact you make with the speaker might not seem to affect your

quality of experience, but for the speaker, it does. When 50, 100, or

5,000 people can give 10% more of their attention and energy to

you—whether through their eye contact, posture, or laughter—it makes the

difference between feeling confident and feeling lost. One extra pair of

friendly eyes, or the visibility of an affirmative nod now and then,

changes how any speaker feels. And in a good room—whether you’re at a

concert or presentation—energy moves easily between the crowd and the

stage.

Even in bad clubs, musicians have many advantages for controlling

the energy in a room—bass drums and amplified guitars literally force

waves

of energy to bounce around, getting people to dance or

respond in various other ways. But in a grey, boring square room of right

angles on top of right angles—where half the crowd mostly sees the bald

spots in the hairlines of the people sitting in front of them, and where

instead of a bass drum, they hear the whiny voice of, for example, the

head of accounting droning on about the right way to fill out page 9,

section F of the new expense reports—the energy in the room is split and

fractured well before it leaves the stage. It bounces around, gets eaten

by the walls, drained by the dull carpet, smothered by the dim lights, and

dies. A speaker, unarmed

with a guitar or bongos, is on his own to overcome the

deficiencies of the space. Even good speakers are frequently eaten alive

by the effects of bad rooms.