Confessions of a Public Speaker (2 page)

Read Confessions of a Public Speaker Online

Authors: Scott Berkun

Tags: #BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Skills

My brain snapped into gear and I looked out into the crowd to get my

bearings. My eyes, on their way back to the center of the room, stopped at

the countdown timer. There I found a surprise. Instead of the 10 minutes I

expected—the 10 minutes I’d planned, prepared, and practiced for—I had

only 9 minutes and 34 seconds. Twenty-six of my precious seconds were

gone.

I confess here in the comforts of this book, with no audience and no

pressure, 26 seconds doesn’t seem worth complaining about. It’s barely

enough time to tie your shoelaces. But there in the moment, raring to go,

I was caught off guard. I couldn’t imagine how I wasted 26 seconds without

starting. (I’d learn later that Brady’s introduction and my walk across

the big stage explained the lapse.) And as I tried to make sense of this

surprising number, more time went by. My brain—

not as smart as it thinks it is—insisted on playing

detective right there, live on stage, consuming even more precious time. I

don’t know why my brain did this, but my brain does many curious things I

have to figure out later.

Meanwhile, I’m rambling. Blah blah innovation blah creativity blah.

I’m not a blabbermouth in real life, but for 15 seconds I can ramble on

about a subject I know well enough to seem like I’m

not

rambling. Doing this bought me just enough time

for my brain to give

up its pointless investigation of what happened. Finally

focused, I had to waste even more time managing the surgery-like segue

between my rambles and the first point of my prepared material.

Confidently back on track, despite being a full minute behind, I hit the

remote to advance the slide. But when I did, I held it too long and two

slides flew by.

We all have reserve tanks of strength that help us cope when things

go wrong, but here mine hit empty. I didn’t have the courage to stop my

talk, ask the tech folks over the microphone—as if speaking to the gods

above—to go back, while just standing there on stage, waiting helplessly

as the clock ate even more of my precious seconds. So, I pressed on, did

my best, and fled the stage after my 10 minutes ended.

It was a disaster to me. I never found my rhythm and couldn’t

remember much of what I’d said. But as I talked with people I knew in the

audience, I discovered something much more interesting. Not

only did no one care, no one noticed. The drama was mostly in my own mind.

As Dale Carnegie wrote in

Public Speaking for Success

:

[

4

]

Good speakers usually find when they finish that there

have been four versions of the speech: the one they delivered, the one

they prepared, the one the newspapers say was delivered, and the one on

the way home they wish they had delivered

.

You can watch the 10-minute video of the talk and see for

yourself.

[

5

]

It’s not an amazing presentation, but it’s not a bad one

either. Whatever mistakes and imperfections exist, they’re larger in my

head than in yours. My struggles on stage that night taught me a lesson:

never plan to use the full time given. Had I planned to go 9 minutes

instead of 10, I wouldn’t have cared what the clock said, how weird the

remote was, or how long it took me to cross the stage.

And it’s often the case that the things speakers obsess about are

the opposite of what the audience cares about. They want to be

entertained. They want to learn. And most of all, they want you to do

well. Many mistakes you can make while performing do not prevent those

things from happening. It’s the mistakes you make before you even say a

word that matter more. These include the mistakes of not having an

interesting opinion, of not thinking clearly about your points, and of not

planning ways to make those points relevant to your audience. Those are

the ones that make the difference. If you can figure out how to get those

right, not much else will matter.

[

1

]

I asked more than a dozen experts, and while none knew of the

origins of the advice, Richard I. Garber tracked down a mention in

expert James C. Humes’s book

The Sir Winston

Method

(Quill) connecting Churchill to it.

[

2

]

Some speeches are more formal than others, so you

can

find examples of perfect readings (but these

are uncommon). I listened to

Greatest Speeches of All

Time

, Vol. I and Vol. II, and many speeches support this

point.

[

3

]

For keynotes at some large events, there are several computers

set up to run the same slides just in case one crashes. For it to

work, the remote control is attached to the custom system, not to any

one computer; thus, the funky remote.

[

4

]

(Tarcher), p. 61.

[

5

]

Forty-eight seconds into the video, you can see the expression

on my face as I see two of my slides fly by:

http://www.blip.tv/file/856263/

.

"

The best speakers know enough to be scared…the only

difference between the pros and the novices is that the pros have

trained the butterflies to fly in formation

.”

—Edward R.

Murrow

While there are good reasons why people fear public speaking, until

I see someone flee from the lectern mid-presentation, running for his life

through the fire exit on stage left, we can’t say public speaking is

scarier

than

death. This oddly popular factoid, commonly stated as, “Did

you know people would rather die than speak in public?”, is a classic case

of why you should ask people how they know what they think they know. This

“fact” implies that people will, if given the chance, choose to jump off

buildings or swallow cyanide capsules rather than give a short

presentation to their coworkers. Since this doesn’t happen in the real

world—no suicide note has ever mentioned an upcoming presentation as the

reason for leaving this world—it’s worth asking: where does this factoid

come from?

The source is

The Book of Lists

by David

Wallechinksy et al. (William Morrow), a trivia book first

published in 1977. It included a list of things people are afraid of, and

public speaking came in at number one. Here’s the list, titled “The Worst

Human Fears”:

Speaking before a group

Heights

Insects and bugs

Financial problems

Deep water

Sickness

Death

Flying

Loneliness

Dogs

Driving/Riding in a car

Darkness

Elevators

Escalators

People who mention this factoid haven’t seen the list because if

they had, they’d know it’s too silly and strange to be taken seriously.

The Book of Lists

says a team of market researchers

asked 3,000 Americans the simple question, “What are you most afraid of?”,

but they allowed them to write down as many answers as they wanted. Since

there was no list to pick from, the survey data is far from scientific.

Worse, no information is provided about who these people were.

[

6

]

We have no way of knowing whether these people were

representative of the rest of us. I know I avoid most surveys I’m asked to

fill out, as do many of you, which begs the question why we place so much

faith in survey-based research.

When you do look at the list, it’s easy to see that people fear

heights (#2), deep water (#5), sickness (#6), and flying (#8) because of

the likelihood of dying from those things. Add them up, and

death easily comes in first place, restoring the Grim

Reaper’s fearsome reputation.

[

7

]

Facts about public speaking are often misleading since they

frequently come from people selling services, such as books, that benefit

from making public speaking seem as scary as possible. Even if the

research were done properly, people tend to list fears of minor things

they encounter in everyday life more often

than more fearsome but abstract experiences like

dying.

When thinking about fun things like death, bad surveys, and public

speaking, the best place to start is with the realization that no has died

from giving a bad presentation. Well, at least one person did, President

William Henry Harrison, but he developed pneumonia after giving the

longest inaugural address in U.S. history. The easy lesson from his story:

keep it short, or you might die. This exception aside, by the time you’re

important enough—like Gandhi or Lincoln—for someone to want to kill you,

it’s not the public speaking that’s going to do you in. Malcolm X was shot

at the beginning of a speech in 1965, but he was a fantastic speaker (if

anything, he was killed because he spoke too well). Lincoln was

assassinated

watching

other people on stage. He was

shot from behind his seat, which points out one major advantage of giving

a lecture: it’s unlikely someone will sneak up from behind you to do you

in without the audience noticing. Being on stage behind a lectern gave

safety to President George W. Bush in his last public appearance in Iraq

when, in disgust, an Iraqi reporter threw one, then a second, shoe at him.

Watching the onslaught from the stage, Bush had the advantage and nimbly

dodged them both.

The real danger is always in the crowds. Fans of rock bands like The

Who, Pearl Jam, and the Rolling Stones have been killed in the stands. And

although the drummer

for Spinal Tap did mysteriously explode while performing,

very few real on-stage deaths have ever been reported in the history of

the world. The danger of crowds is why some people prefer the aisle

seats—they can quickly escape, whether they’re fleeing from fire or

boredom. If you’re on stage, not only do you have better access to the

fire exits, but should you faint, fall down, or suffer a heart attack,

everyone in attendance will know immediately and call an ambulance for

you. The next time you’re at the front of the room to give a presentation,

you should know that, by all logic, you are the safest person there. The

problem is that our brains are wired to believe the opposite; see

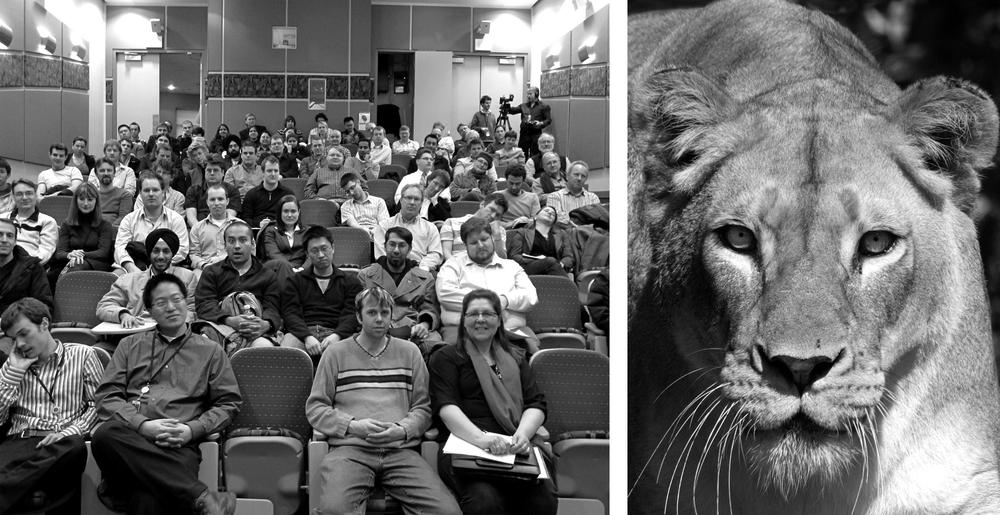

Figure 2-1

.

Figure 2-1. When you see the left, your brain sees the right.

Our brains, for all their wonders, identify the following four

things as being very bad for survival:

Standing alone

In open territory with no place to hide

Without a weapon

In front of a large crowd of creatures staring at you

In the long history of all living things, any situation where all

the above were true was very bad

for you. It meant the odds were high that you would soon be

attacked and eaten alive. Many predators hunt in packs, and their easiest

prey are those who stand alone, without a weapon, on a flat area of land

where there is little cover (e.g., a stage). Our ancestors, the ones who

survived, developed a fear response to these situations. So, despite my 15

years of teaching classes, running workshops, and giving lectures, no

matter how comfortable I appear to the audience when at the front of the

room, it’s a scientific fact that my brain and body will experience some

kind of fear before and often while I’m speaking.

The design of the brain’s wiring—given its long operational history,

which is hundreds of thousands of years older than the history of public

speaking, or speaking at all, for that matter—makes it impossible to stop

fearing what it knows is the worst tactical situation for a person to be

in. There is no way to turn it off, at least not completely. This wiring

is so primal that it lives in the oldest part of our brains where, like

many of the brain’s other important functions, we have almost no

control.

Take, for example, the simple act of breathing. Right now, try to

hold your breath. The average person can go for a minute or so, but as the

pain intensifies—pain generated by your nervous system to stop you from

doing stupid things like killing yourself—your body will eventually force

you to give in. Your brain desperately wants you to live and will do many

things without asking permission to help you survive. Even if you’re

particularly stubborn and you make yourself pass out from lack of oxygen,

guess what happens? You live anyway. Your ever-faithful amygdala, one of

the oldest parts of your brain, takes over, continuing to regulate your

breathing, heart rate, and a thousand other things you never think about

until you come to your senses (literally and figuratively).

For years, I was in denial about my public speaking fears. After

seeing me speak, when people asked whether I get nervous, I always did the

stupid machismo thing. I’d smirk, as if to say, “Who me? Only mere mortals

get nervous.” At some level, I’d always known my answer was bullshit, but

I didn’t know the science, nor had I studied what others had to say. It

turns out there are consistent reports from

famous public figures confirming that, despite their talents

and success, their brains have the same wiring as ours:

Mark

Twain, who made most of his income from speaking, not

writing, said, “There are two types of speakers: those that are

nervous and those that are liars.”Elvis

Presley said, “I’ve never gotten over what they call

stage fright. I go through it every show.”Thomas Jefferson was so afraid of public speaking that he had

someone else read the State of the Union address (George Washington

didn’t like speaking either).

[

8

]Bono, of U2, claims to get nervous the morning of every one of

the thousands of shows he’s performed.Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, Margaret Thatcher, Barbara

Walters, Johnny Carson, Barbra Streisand, and Ian Holm have all

reported fears of public communication.

[

9

]Aristotle, Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Winston Churchill, John

Updike, Jack Welch, and James Earl Jones all had stutters and were

nervous speakers at one time in their lives.

[

10

]

Even if you could completely shut off these fear-response systems,

which is the first thing people with fears of public speaking want to do,

it would be a bad idea for two

reasons. First, having the old parts of our brains in

control of our fear responses is a good thing. If a legion of escaped

half-lion, half-ninja warriors were to fall through the ceiling and

surround you—with the sole mission of converting your fine flesh into thin

sandwich-ready slices—do you want the burden of consciously deciding how

fast to increase your heart rate, or which muscles to fire first to get

your legs moving so you can run away? Your conscious mind cannot work fast

enough to do these things in the small amount of time you’d have to

survive. It’s good that fear responses are controlled

by the subconscious parts

of our minds, since those are the only parts with fast

enough wires to do anything useful when real danger happens.

The downside is that this fear-response wiring causes problems

because our lives today are very safe. Few of us are regularly chased by

lions or wrestle alligators on our way to work, making our fear-response

programming out of sync with much of modern life. As a result, the same

stress responses we used

for survival for millions of years get applied to

nonsurvival situations by our eager brains. We develop ulcers, high blood

pressure, headaches, and other physical problems in part because our

stress systems aren’t designed to handle the “dangers” of our brave new

world: computer crashes, micromanaging bosses, 12-way conference calls,

and long commutes in rush-hour traffic. If we were chased by tigers on the

way to give a presentation, we’d likely find the presentation not nearly

as scary—our perspective on what things are worth fearing would have been

freshly calibrated.

Second, fear focuses attention. All the fun, interesting things in

life come with fears. Want to ask that cute girl out on a date? Thinking

of applying for that cool job? Want to write a novel? Start a company? All

good things come with the possibility of failure, whether it’s rejection,

disappointment, or embarrassment, and fear of those failures is what

motivates many people to do the work necessary to be successful. That fear

gives us the energy to proactively prevent failures from happening. Many

psychological causes of fear in work situations—being laughed at by

coworkers or looking stupid in front of the boss—can also be seen as

opportunities to impress or prove your value. Curiously enough, there may

be little difference biologically between fear of failure and anticipation

of success. In his excellent book

Brain Rules

(Pear Press), Dr. John

Medina points out that it is very difficult for the body to

distinguish between states of arousal and states of anxiety: