Confessions of a Public Speaker (7 page)

Read Confessions of a Public Speaker Online

Authors: Scott Berkun

Tags: #BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Skills

The worst situation, even worse than being in a bad room, is being

in a big, bad empty room.

Speaking in a huge, boring, rectangular, dimly lit room that

seats 1,000 people is challenging enough, but with only 100 attendees

present, these rooms feel like black holes. Even if you’re screaming,

dancing, and juggling knives, it may not be possible to generate enough

energy to fill the space. I once saw U2 play at the Meadowlands in New

Jersey, which holds 60,000 people. By the end of the show, people were

streaming out to beat the traffic, and no matter what Bono did on stage,

the stadium was dead. There were still 20,000 dancing people there, but it

seemed like the lamest 20,000 people I’d ever seen.

A related personal disaster took place when I spoke at Microsoft’s

Tech-Ed conference in Dallas in 1998. I drew the short straw: I had the

largest room of the entire massive hotel conference center complex. The

ceilings were so high, and the back wall was so distant from the stage,

that I actually asked the tech crew if it was a converted aircraft hangar.

It must have been used for something other than training events. There was

no reason for this room to have the scale it did, other than to torture

public speakers. The crew looked up at the ceiling when I asked, and were

sort of surprised there was a ceiling there at all. They never thought to

look up, as they spend most of their time just trying to fix all the stuff

that breaks down at ground level. I should have told them about how stars

hover in the night sky—it would have blown their minds.

The room was set

with chairs for over 2,000 people. When I heard this, my ego

lit up: 2,000 people? To see me? Wow. I must be super cool. But as the

countdown timer ticked away—20 minutes, 10 minutes, 5—

and I’d spent all that time staring out at a sea of empty

seats, I was mortified. I didn’t want to go on. I’d never seen so many

empty chairs all in one place. Where did they keep them? There must have

been a huge storeroom just for these chairs. How utterly pathetic for

someone to have spent an afternoon arranging them all, only for those

chairs to sit empty and unloved. And how depressing that I was the person

who had failed to fill them.

With a minute to go, a few people were seated here and there. A

handful more walked in from the back exit, like little ants entering my

zip code–

sized room (you always get a few at the last minute). It was

nice to see them, but they quickly disappeared into the cave-like darkness

between the aisles. With 20 seconds to go, I noticed one guy up front,

finally aware of the tumbleweeds drifting past him, grab his things and

scurry toward the door. So much for him. Five seconds. The house lights

came up and with them came a wave of heat over my face and arms. The few

pairs of eyes in the room were now all on me. It was time to start.

What could I do? Was there anything that could be done? My body

chose to panic. Having panicked before, I knew the only trick was to

start, as fear comes from what you imagine might happen instead of what

actually is happening, and the longer you wait, the worse it gets. The

only way to kill this evil feedback loop is to just do it, so I forced

myself to begin. And I sucked. For an hour I sucked—an endless hour of

misery, speaking into the Grand Canyon of rooms, with each and every word

traveling slowly across a sea of empty chairs. I heard every word twice,

once when I said it, and two seconds later when it echoed against the back

wall, unimpeded by the sound-absorbing powers of an actual crowd. When I

finished, I sulked my way to a dark corner of the hotel bar, hid behind a

row of beers, and hoped not to be seen.

The solution to this, and to many other tough room

problems, rests on the density theory of public speaking, a

theory I discovered one day after repeating the Dallas experience in some

other city, with some other embarrassingly

small crowd in a ridiculously large room. I realized that

the crowd size is irrelevant—what matters is having a

dense

crowd. If ever you face a sparsely populated

audience, do whatever you have to do to get them to move together. You

want to create a packed crowd located as close as possible to the front

of the room. This goes against most speakers’ instincts,

which push them to just go on with the show

and pretend not to notice it feels like they’re speaking at

the Greyhound bus station at 3 a.m. on Christmas morning.

Those few people in the audience know as well as you do that the

room is empty, and if you act like you don’t notice, they’ll know you’re

full of shit before you get five minutes into your talk. Audiences, even

tough crowds, genuinely want to help you, but no one in the audience can

do anything about bad energy. Only two people in the room have that

control: the host and the speaker. The host, a person who likely knows

little about public speaking (much less the density theory), and who

probably has 25 other event problems more important than your empty room,

is unlikely to be of use. Hell, he chose to put you in the room of certain

death to begin with. So all hope rests in the hands of whoever has the

microphone, and that’s you (see

Figure 4-4

).

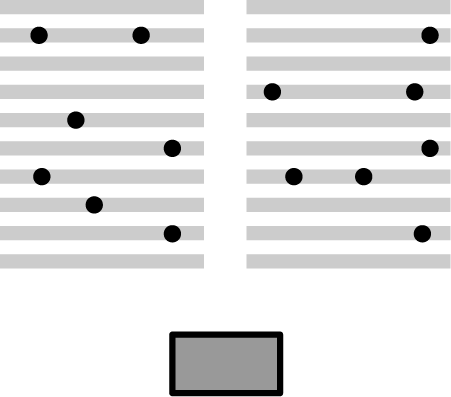

Figure 4-4. A small crowd in a big room. Your energy can never effectively

reach everyone because it will be eaten by all the dead space.

Forty-five people in a 2,000-person room is not a crowd, it’s the

equivalent devastation of a neutron bomb. This means the first move is to

forget the 2,000 seats. Forget the empty rows and dead spaces. Imagine a

smaller room inside the big one that seats about 50 people

(see

Figure 4-5

). Make

the room your own by asking the attendees to gather into that more

intimate space. If you leave them scattered in the

wasteland

of empty seats, they will feel like lonely losers. They will

feel embarrassed for having chosen to come see you instead of any of a

thousand other nonembarrassing things they could have done with their

hour. If you pack them together, at least they’ll know they’re not the

only losers who decided to come hear you. They are now losers with loser

friends, which—all things considered—is much better than being a loser

without any friends at all. They are, in fact, your losers, so you should

treat them well.

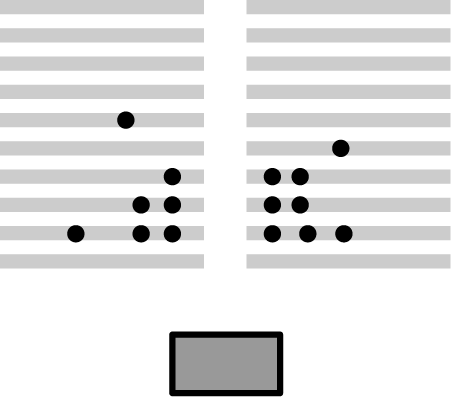

Figure 4-5. A properly arranged small crowd in a big room. You can do good

work here despite the empty space.

The tricky part is getting people to move. We are a lazy species. I

know once I’m seated I’m not very interested in getting up just to sit

down again. But the fact is, all of us do what people in authority tell us

to do, especially in lecture halls. We have spent our lives listening to

people at the front of crowded rooms telling us to stand up, sit down,

sing songs, close our eyes, play “Simon Says,” repeat national anthems,

and a thousand other stupid things we’d never agree to do if we weren’t

being dictated to by someone with a microphone. It doesn’t matter where

you are or how scared the crowd suspects you might be, if you have the

mike

and explain the situation with a smile, when you ask them

nicely to stand up and move forward, they will. Make it a game. Offer a

prize to the person who gets up first. Ask the

audience members if they need more exercise today, and when

they all raise their hands (people who go to lectures and conferences

always crave exercise), tell them you have just the thing for them to do.

You might eat a few minutes of your time, but it’s worth it if you have a

long session. And whoever speaks to the same crowd after you will be

grateful.

The few that don’t oblige should be left in the back of the room

anyway. There’s no law stating that you must treat everyone in the

audience the same. Give preferential treatment to the people who respond

to your requests. By making them move, you’ve done a few other beneficial

things. They’ve now invested something in you, and you will have their

attention for at least the next two minutes. You spoke the truth about the

uncomfortable nature of the room, and people will respect your honesty and

willingness to take action to fix it. And for your sake, you’ve identified

the leaders and fans: they’re the ones who got up first. These are the

people most interested in you and what you have to say. If there are any

allies in the crowd—the people first to applaud or ask a question—you now

know who they are.

Most importantly, the density theory amplifies your energy. We’re

social creatures. If five people—or even dogs, raccoons, or other social

animals—get together, they start to behave in shared ways. They make

decisions together, they move together, and most importantly, they become

a kind of short-term community. With a tightly packed crowd, if I make one

person laugh, nod his head, or smile, the people directly adjacent will

notice and be slightly more prone to do it themselves. TV sitcoms have

laugh tracks for this reason: we respond to what the crowd around us is

doing. Even simply having the woman next to you listening with her full

attention changes the atmosphere for the better, versus sitting next to an

annoying dude checking his email who doesn’t look up once. The

size of the room or the crowd becomes irrelevant as long as

the people there are together in a tight pack, experiencing and sharing

the same thing at the same time.

There are many similar adjustments a speaker can make to a room.

Turn up the lights if it feels like you’re in a cave. Ask for a wireless

microphone or bring your own if you hate being tied to the lectern. If you

spot someone stuck behind a pole or standing in the back, offer him a seat

near the front that he might not have noticed was empty. Always travel

with a remote for your laptop so you can move to a better spot if the

lectern was placed in some stupid back corner of the stage. Ask the crowd

if they’re too cold or too warm, and then, on the mike, ask the organizers

to do something about it (even if they can’t, you look great by being the

only speaker to give a care about how the audience is feeling). There are

always little things you can do—that don’t require the construction of

your own private lecture theater—to improve how the room feels. When you

have the microphone, it’s your room—do whatever you’d like to enhance the

audience’s experience.

Failing to own your turf is the big mistake that can create a tough

crowd. If I show up five minutes before I start speaking, I have no idea

what the vibe is like. Every audience is different for a thousand reasons,

from what the traffic was like that morning to what sports team won or

lost the night before to what community politics are happening. If I just

show up right before my talk, I can’t sort out how much of it has to do

with me as opposed to general hatred for the world at large. Taking

responsibility for the crowd means showing up to the room early enough to

at least hear the previous speaker. Sometimes you’ll hear a joke or

comment in the previous talk that you can pick up on, or know to avoid,

given that it’s been used before. If the speaker was awesome but only got

cold stares from the crowd, you know something is up that’s larger than

you or the other speaker. But if he does well and gets great energy and

strong applause, yet you go down in flames, you know it’s not the

audience—it’s you.

Speaking in foreign countries makes this all too clear. You have no

idea what a tough crowd is until you’ve spoken in Sweden, Japan, or scores

of other countries where laughing, joking, and yelling out support during

a presentation are cultural taboos. And unless you speak the local

language, you’re being translated, which means the audience doesn’t know

what you said—or what the translator decided you said—until about 10

seconds after you’ve said it. When I spoke in Moscow, live translated just

like at the United Nations, the audience was awesome, but I didn’t know

why they were laughing until the translator explained it through my

earpiece. For long, horrible moments, I was afraid they were laughing at

or heckling me, rather than supporting what I’d said. After speaking

through live translation a few times, presenting to a rowdy crowd is a

breeze if they speak your native language.