Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (7 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

The double-headed eagle of the house of Palaiologos

In this confusion, the Ottoman advance into Europe continued unchecked. In 1362 they virtually encircled Constantinople from the rear when they took the city of Adrianople – Edirne in Turkish – 140 miles to the west, and moved their imperial capital into Europe. When they shattered the Serbs in battle in 1371 the Emperor John was isolated from all Christian support and had little option but to become a vassal of the sultans, contributing troops on demand and seeking permission for imperial appointments. The advance of the Ottomans seemed unstoppable: by the end of the fourteenth century their terrain stretched from the Danube to the Euphrates. ‘Turkish or heathen expansion is like the sea,’ wrote the Serbian, Michael ‘the Janissary’, ‘it never has peace but always rolls … until you smash a snake’s head it is always worse.’ The Pope issued a bull proclaiming crusade against the Ottomans in 1366, and in vain threatened excommunication against the trading states of Italy and the Adriatic for supplying them with arms. The next fifty years were to see three crusades against the infidel, all led by the Hungarians, the most threatened state in Eastern Europe. They were to be the swan song of a united Christendom. Each one ended in punishing defeat, the causes of which were not hard to find. Europe was divided, poverty stricken, wracked by its own internal disputes, weakened by the Black Death. The armies themselves were lumbering, quarrelsome, ill disciplined and tactically inept, in comparison with the mobile and well organized Ottomans, unified around a common cause. The few Europeans who saw them up close could not but profess a sneaking admiration for ‘Ottoman order’. The French traveller Bertrandon de la Brocquière observed in the 1430s:

They are diligent, willingly rise early, and live on little … they are indifferent as to where they sleep, and usually lie on the ground … their horses are good, cost little in food, gallop well and for a long time … their obedience to their superiors is boundless … when the signal is given, those who are to lead march quietly off, followed by the others with the same silence … ten thousand Turks on such an occasion will make less noise than 100 men in the Christian armies … I must own that in my various experiences I have always found the Turks to be frank and loyal, and when it was necessary to show courage, they have never failed to do so.

Against this background the start of the fifteenth century looked bleak for Constantinople. Siege by the Ottomans had become a recurring feature of life. When the Emperor Manuel broke his oath of vassalage in 1394, Sultan Bayezit subjected the city to a series of assaults, only called off when Bayezit was himself defeated in battle by the Turkic Mongol, Timur – the Tamburlaine of Marlowe’s play – in 1402. Thereafter the emperors sought increasingly desperate help from the west – Manuel even came to England in 1400 – whilst pursuing a policy of diplomatic intrigue and support for pretenders to the Ottoman throne. Sultan Murat II besieged Constantinople in 1422 for encouraging pretenders but the city still held out. The Ottomans had neither the fleet to close off the city nor the technology quickly to storm its massive land walls and Manuel, by now an old man but still one of the most astute of all diplomats, managed to conjure up another claimant to the Ottoman throne to threaten civil war. The siege was lifted, but Constantinople was hanging on by the skin of its teeth. It seemed only a matter of time before the Ottomans came for the city again and in force. It was only the fear of a concerted European crusade that restrained them.

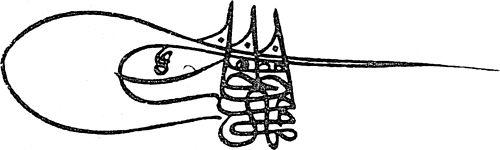

The tugra, the imperial cipher, of Orhan, the first sultan to take a city by siege

2 Dreaming of Istanbul

1

‘I have seen that God …’, quoted Lewis,

Islam from the Prophet

, vol. 2, pp. 207–8

2

‘Sedentary people …’, Ibn Khaldun, vol. 2, pp. 257–8

3

‘to revive the dying …’, Ibn Khaldun, quoted Lewis,

The Legacy of Islam,

p. 197

4

‘God be praised …’, quoted Lewis,

Islam from the Prophet

, vol. 2, p. 208

5

‘On account of its justice …’, quoted Cahen, p. 213

6

‘an accursed race … from our lands’, quoted Armstrong, p. 2

7

‘they are indomitable …’, quoted Norwich, vol. 3, p. 102

8

‘we must live in common …’, quoted Mango,

The Oxford History of

Byzantium,

p. 128

9

‘Constantinople is arrogant …’, quoted Kelly, p. 35

10

‘since the beginning …’, quoted Morris, p. 39

11

‘so insolent in …’, quoted Norwich, vol. 3, p. 130

12

‘they brought horses …’, quoted ibid., vol. 3, p. 179

13

‘Oh city …’, quoted Morris, p. 41

14

‘situated at the junction …’, quoted Kinross, p. 24

15

‘It is said that he …’, quoted Mackintosh-Smith, p. 290

16

‘Sultan, son of …’, quoted Wittek, p. 15

17

‘The Gazi is …’, quoted ibid., p. 14

18

‘Why have the Gazis …’, quoted ibid., p. 14

19

‘in such a state …’, Tafur, p. 146

20

‘Turkish or heathen …’, Mihailovich, pp. 191–2

21

‘They are diligent …’, Brocquière, pp. 362–5

1432–1451

Mehmet Chelebi – Sultan – may God fasten the strap of his authority to the pegs of eternity and reinforce the supports of his power until the predestined day!

Inscription on the tomb of the mother of Mehmet

IIConstantine Palaiologos, in Christ true Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans.

Ceremonial title of Constantine XI, eighty-eighth Emperor of Byzantium

The man destined to tighten the Muslim noose on the city was born ten years after Murat’s siege. In Turkish legend, 1432 was a year of portents. Horses produced a large number of twins; trees were bowed down with fruit; a long-tailed comet appeared in the noonday sky over Constantinople. On the night of 29 March, Sultan Murat was waiting in the royal palace at Edirne for news of a birth; unable to sleep, he started to read the Koran. He had just reached the Victory suras, the verses that promise triumph over unbelievers, when a messenger brought word of a son. He was called Mehmet, Murat’s father’s name, the Turkish form of Muhammad.

Like many prophecies, these have a distinctly retrospective feel to them. Mehmet was the third of Murat’s sons; both his half-brothers were substantially older and the boy was never his father’s favourite. His chances of living to become sultan were slim. Perhaps it is significant of the entry Mehmet made into the world that considerable uncertainty surrounds the identity of his mother. Despite the efforts of some Turkish historians to claim her as an ethnic Turk and a Muslim,

the strong probability is that she was a western slave, taken in a frontier raid or captured by pirates, possibly Serbian or Macedonian and most likely born a Christian – a parentage that casts a strange light on the paradoxes in Mehmet’s nature. Whatever the genetic cocktail of his origins, Mehmet was to reveal a character quite distinct from that of his father, Murat.

By the middle of the fifteenth century Ottoman sultans were no longer unlettered tribal chieftains who directed war bands from the saddle. The heady mixture of jihad and booty had given way to something more measured. The sultan still derived immense prestige as the greatest leader of holy war in the lands of Islam, but this was increasingly a tool of dynastic policy. Ottoman rulers now styled themselves the ‘Sultan of Rum’ – a title that suggested a claim to the inheritance of the ancient Christian empire – or ‘Padishah’, a high-flown Persian formula. From the Byzantines they were developing a taste for the ceremonial apparatus of monarchy; their princes were formally educated for high office; their palaces were high-walled; access to the sultan became carefully regulated. Fear of poison, intrigue and assassination were progressively distancing the ruler from his subjects – a process that had followed the murder of Murat I by a Serbian envoy after the first Battle of Kosovo in 1389. The reign of the second Murat was a fulcrum in this process. He still signed himself ‘bey’ – the old title for a Turkish noble – rather than the grander ‘sultan’ and was popular with his people. The Hungarian monk, Brother George, was surprised by the lack of ceremonial surrounding him. ‘On his clothing or on his horse the sultan had no special mark to distinguish him. I watched him at his mother’s funeral, and if he had not been pointed out to me, I could not have recognised him.’ At the same time a distance was starting to be interposed between the sultan and the world around him. ‘He never took anything in public’, noted Bertrandon de la Brocquière, ‘and there are very few persons who can boast of having seen him speak, or having seen him eat or drink.’ It was a process that would lead successive sultans to the hermetic world of the Topkapi Palace with its blank outer walls and elaborate ritual.

It was the chilly atmosphere of the Ottoman court that shaped Mehmet’s early years. The issue of succession to the throne cast a long shadow over the upbringing of male children. Direct dynastic succession from father to son was critical for the empire’s survival – the harem system was instrumental in ensuring an adequate supply of surviving

male children to protect it – but comprised its greatest vulnerability. The throne was a contest between the male heirs. There was no law prioritizing the eldest; the surviving princes simply fought it out at the sultan’s death. The outcome was considered to be God’s will. ‘If He has decreed that you shall have the kingdom after me,’ a later sultan wrote to his son, ‘no man living will be able to prevent it.’ In practice, succession often became a race for the centre – the winner would be the heir who secured the capital, the treasury and the support of the army; it was a method that might either favour the survival of the fittest or lead to civil war. The Ottoman state had nearly collapsed in the early years of the fifteenth century in a fratricidal struggle for power in which the Byzantines were deeply implicated. It had become almost state policy in Constantinople to exploit the dynasty’s moment of weakness by supporting rival claimants and pretenders.