Crete: The Battle and the Resistance (19 page)

Read Crete: The Battle and the Resistance Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #War, #History

Also on that first morning, one of the companies of II Battalion of the Storm Regiment, which landed several kilometres south-west of Maleme, was surprised by Cretan irregulars when sent on to secure the pass near Koukouli. But the most contentious episode of the whole battle concerned Lieutenant Mürbe's detachment. This group, seventy-two strong, which dropped on the edge of Kastelli Kissamou to capture the port, was ferociously engaged by the 1st Greek Regiment and Cretan irregulars. Mürbe and fifty-three of his men were killed, the rest became prisoners. A number of German corpses were hacked about by civilians, but there is little evidence to support the claims made afterwards by Goering and Goebbels that many wounded paratroopers were tortured and mutilated while still alive.

The Germans, partly lulled by the intelligence prediction that the Cretans would welcome them, were completely taken by surprise. And the scale of their losses enraged them. On the first day alone 1,856

paratroopers had been killed. That figure must have swelled to over 2,000 as the mortally wounded died. To assess how many the Cretans had killed is impossible, but the shock to the Germans was unmistakable. They had come to expect their chosen enemy to cave in at the approach of what they liked to call

der Furor Teutonicus

in imitation of the Spanish infantry's

furia espanola

in the fifteenth century. Civilian resistance, while an ancient tradition in Crete, so deeply offended the Prussian sense of military order that brutal reprisals were taken against the local population.

10

Maleme and Prison Valley

20 May

General Freyberg had done his best to get inessential people off the island before the battle started.

Colonel James Roosevelt, son of the US President, had been persuaded to leave by Sunderland flying-boat only thirty-six hours before the invasion. But the King of Greece was still on Crete.

The royal party had left the Bella Kapina and arrived at a villa near Perivolia on 19 May. Prince Peter joined them there that evening from his house on the coast north of Galatas, only a few kilometres away. Next morning, Colonel Jasper Blunt, who knew the enemy plan having served as Freyberg's chief intelligence officer after his arrival from Greece, began telephoning Creforce Headquarters for news from seven o'clock, when the first air raids began along the coast. Anxiously watching the sky through binoculars, he spotted the first wave of Junkers transport planes and the first sticks of paratroopers. Blunt cranked the field telephone in an urgent attempt to ring Creforce Headquarters again, but without success. A bomb had already severed the landline.

One group of paratroopers landed less than a kilometre away. Blunt ordered the escort platoon of New Zealanders to grab their weapons, and leave their bedrolls and blankets. There was not even time to pack up the wireless set. He chivvied his charges, who included the King, Prince Peter, Colonel Levidis, the court chamberlain, a long-standing friend with whom the King quarrelled as if they were

'an old married couple', and the Prime Minister, Mr Tsouderos.

They had to hurry up the hill behind the house, leaving most of their belongings. The platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Ryan, then deployed around the party, sections forming advance, rear and flank guards.* Another parachute drop made them veer to the left, and scrambling up the hill behind Perivolia, they came under fire from an outlying detachment of the 2nd Greek Regiment. The King and Prince Peter went forward to prove their identity to the wary soldiers.

* Prince Peter's story of paratroopers landing with special maps showing the Bella Kapina, which the party had left the day before, marked with an arrow and

'Koenig hier!'

is a little fanciful considering the scarcity of German intelligence.

Fifth-column fever gripped a number of British and Greek officers in Greece and Crete, but much less so than in France where rumours had circulated of paratroopers dressed as nuns.

Later, when the party stopped to rest, the King was clearly preoccupied. He had left behind some important papers and medals, including the Order of the Garter. (This oversight was curiously reminiscent of an incident in 1620. Fleeing from imperial troops after the Battle of the White Mountain, Frederick, King of Bohemia and the husband of the Winter Queen, left behind on their bed the Garter, which his father-in-law James I had given him.) A section of New Zealanders under the platoon sergeant was sent back for King George's decorations, but they found that German paratroopers had already occupied the house.

Blunt was concerned. With such a vulnerable and unwieldy group, the escort was only adequate against a handful of paratroopers, yet their number was large enough to attract the attention of German aircraft. And their rapid departure without the wireless set meant that he had no way of contacting Creforce Headquarters to find out about evacuation plans from the south coast. He needed information on parachute drops, but Creforce's ignorance of events was almost as great as that of the party wandering on the mountainside.

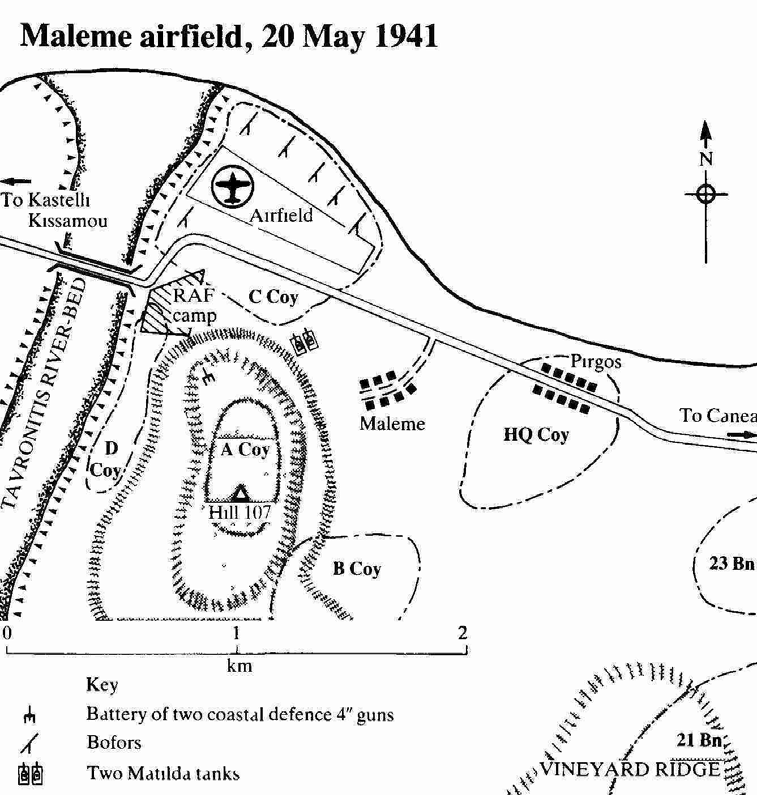

At Maleme, the 22nd Battalion's command post could no longer speak by field telephone to brigade headquarters, and Colonel Andrew knew nothing of what was happening to his two forward companies, C and D, on the airfield and on the Tavronitis side of Hill 107. They could not be seen either from his command post or from neighbouring company positions, and they lacked a wireless set. Thus no reports were available on the enemy's progress against the airfield, one of his main objectives.

Colonel Andrew's area of responsibility round the airfield and Hill 107, the main objectives of the enemy attack, consisted of about five square kilometres of very uneven terrain with dead ground.

Visibility was further impaired by the bamboo thickets, vineyards and olive trees. To make matters worse, he still had no idea of the size of the parachute forces which had landed beyond the Tavronitis.

Nothing had been heard from his observation posts which, since they also lacked wireless sets, were unable to send a warning. Enemy air attack was too heavy and too constant for a runner to stand a good chance of getting through.

The platoon on the airfield nearest to the sea managed to repel attacks along the beach from the mouth of the Tavronitis. But 15 Platoon defending the western end of the airfield was hard-pressed. Only twenty-two strong, lacking machine guns, and responsible for a front over a kilometre wide, they held on with great tenacity.

At ten o'clock, when Braun's paratroopers began probing on to the edge of the airfield, Captain Johnson, the company commander, called for help from the two Matilda tanks of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment. A pair had been hidden next to each airfield. But Colonel Andrew refused: he did not want to play his 'trump card' too early.

Soon, tljp German paratroopers probing round the Tavronitis bridge broke through between the two New Zealand companies and overran the camp. An RAF officer, in an unforgivable oversight, failed to destroy the code-books which, together with Creforce's order of battle, fell into enemy hands.

Keyed-up paratroopers, mostly by instinctive reflex, shot aircraftmen emerging from concealed slit trenches to surrender. One group, however, lined up eight RAF men they found on the surface.

Leading Aircraftman Lawrence shouted at them that they had no right to shoot prisoners without the express order of an officer.

The German paratroopers were so amazed at the idea of prisoners refusing to be shot that an officer was sent for, and they were spared. But those made prisoner were by no means safe. Their captors forced them to march forward as a screen towards Hill 107. This manoeuvre ended in a murderous shambles when a New Zealand section tried to take the German paratroopers in the flank and the prisoners, both RAF and Fleet Air Arm personnel, made a run for it with varying degrees of success.

Other fitters and a couple of officers had already pulled back from the airfield past the thickets of bamboo which obscured the airfield from the positions on the hill behind. They joined up with New Zealand companies and some of them fought effectively as infantrymen for the day.

This confusion did little to help Colonel Andrew assess his position. The 22nd Battalion had started the day 600 strong. It had clearly killed many of the enemy, and yet they were still forcing on to the airfield. Without reports from his observation posts, he had no idea of their true strength. Andrew, as the official history records, 'handicapped by hopelessly bad communications, found it more and more difficult to operate his battalion as a unit'.

The battalion's plight would have been even worse if Major Stentzler and his two companies, trying to attack Hill 107 from the rear, had not clashed with a fortuitously placed platoon. This forced his exhausted and dehydrated men to take an even longer detour through the heat of the day. Their grey parachute overalls had been designed for Northern Europe, and each man's load of weapons, ammunition and emergency pack weighed heavily under the hot sun. Many had drunk most of the water they carried, having sweated almost continuously since the night before.

Colonel Andrew, ignorant of Stentzler's manoeuvre, was far more preoccupied with the fate of his two forward companies. He began to suspect that they had been overrun, and his requests for support became more urgent. At 10.55, he warned brigade headquarters — his wireless set was working intermittently — that contact had been lost with C and D Companies.

Around midday, the Germans brought into action their mortars and a light field-piece parachuted with them. The British artillery batteries could not be used because the field telephone lines from their forward observation officers on Hill 107 had been cut. These gunner officers instead took command of the Fleet Air Arm and RAF personnel.

Colonel Andrew, once again out of contact by wireless, began sending up white and green flares, the emergency signal to the 23rd Battalion, which had been specially designated as the counter-attack force. But the observers positioned to watch for the flares never saw them. Semaphore was also tried.

A message, however, got through to Hargest's headquarters — inexplicably sited six and a half kilometres along the coast at the furthest point from Maleme within the brigade area — at 3.50 p.m.

There was no reaction.

Andrew became increasingly concerned. He had been slightly wounded, although not enough to affect him. With mortar shells falling round his command post, and without news of the forward companies, he began to assume the worst.

At five o'clock, still with no sign of support from Colonel Leckie's 23rd Battalion, he managed to contact Hargest's command post by wireless. But Hargest's reply to his urgent request for support claimed that the 23rd Battalion was engaged with enemy paratroops, an assertion that was unverified and untrue.

Hargest's state of mind is hard to fathom. Either he was hopelessly confused and misinformed or, reflecting Freyberg's priorities, he still regarded attacks on Maleme as secondary in importance to the threat from the sea.

Faced with Hargest's refusal, Colonel Andrew decided that he had to play his trump card. The two Matilda tanks of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment, backed by his reserve platoon which had been made up to strength with some gunner volunteers, were ordered into action. As the ungainly Matildas manoeuvred from their hide on to the coast road, their steel tracks squealed and screeched, a noise inspiring dread in the German paratroopers. But this psychological advantage did not last long.

With extraordinary rashness, the two tanks ignored the enemy on the airfield and in the RAF camp.

Instead, they headed straight for the Tavronitis river-bed. On the way, the crew of the rear tank found that they had the wrong ammunition and that their turret could not traverse properly — a rather tardy discovery — so they turned back, leaving the other Matilda to go on alone.

The lead tank rumbled on towards the bridge, then bumped and lurched down on to the river-bed.

This Matilda turned to attack the German paratroopers in the flank, but almost immediately its armoured belly stuck on a boulder: the tank now resembled a stranded turtle. The crew then found that they too could not traverse their turret, and abandoned the vehicle. Their exposed infantry escort was beaten back with several losses.

At about six o'clock, Andrew contacted Hargest by wireless to tell him of the failure, and that without support from the 23rd Battalion, he would have to withdraw. Hargest replied: 'If you must, you must.'

But he also said he was sending two companies to his aid. Andrew assumed that they would arrive

'almost immediately'. But as darkness fell, with no sign of help, with ammunition running low and still no message from his forward companies, he began to consider a full withdrawal.

It is easy to sympathize with Colonel Andrew's state of mind, but harder to understand why he did not leave his command post, blind on the rear slope of the hill, and attempt to study the scene through binoculars. The forward slope, raked by machine-gun fire, bombed and virtually stripped of vegetation, was certainly a dangerous place, but Andrew's bravery is not in doubt. Like his superior officers in the chain of command upwards — Hargest, Puttick and Freyberg — his imagination and instincts seem to have become shackled to his command post. This did not mean that Andrew was behaving like an ostrich — he did not try to belittle the threat — but his thought processes had jammed.