Crete: The Battle and the Resistance (3 page)

Read Crete: The Battle and the Resistance Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #War, #History

In the next phase, the Cretan Division fought on the central part of the front. In the last few days of January 1941, V Division distinguished itself in the fighting for Mount Trebesina and Klissoura, an important road junction. A single Cretan regiment put the 58th Leniano Division to flight. One of the other enemy formations on this sector was the 51st Siena Division, which later in the war occupied the eastern part of Crete: in 1943, after the Italian armistice, Paddy Leigh Fermor smuggled its commander off the island.

Leigh Fermor, escaping the claustrophobic atmosphere of General Headquarters in Athens, did not pay more attention to V Division on his tour of the Albanian front than to any of the others. The only differences he could recall afterwards were the cheerfulness of the Cretans in spite of the savage cold, and the way they carried their rifles across their shoulders like a yoke, because that was the way Cretan shepherds walked with their crooks. He had no idea then how important Crete was to become.

2

DIPLOMATIC MISSIONS

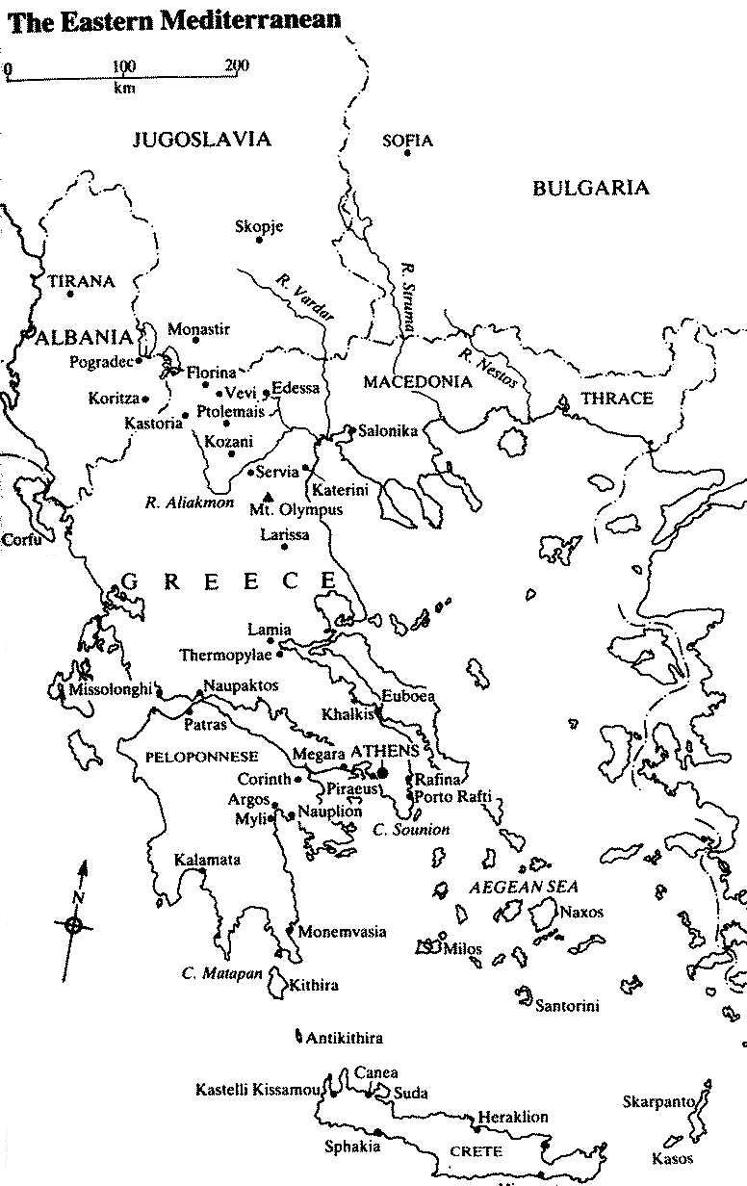

In January 1941, the Greeks, after reinforcing their army in Albania, had only four under-strength divisions left for the Bulgarian border of Thrace and Eastern Macedonia. The Commander-in-Chief, General Papagos, hoped that an alliance with Jugoslavia would enable them to crush the Italians in a pincer so that his divisions could be redeployed should the German threat from Roumania increase.

Papagos, closely supervised by Metaxas, had handled the advance into Albania with sturdy skill, but his determination to beat the Italians became a fixation, and his tunnel vision was to prove disastrous.

The Jugoslav government of the Regent, Prince Paul, in any case appeared a very uncertain ally at that stage. Armies of the Axis and its inchoate allies lay beyond six out of seven of Jugoslavia's borders: those of Italy, Austria, Hungary, Roumania, Bulgaria and Albania. And Prince Paul —

Churchill later dubbed him 'Prince Palsy' — was buckling under pressure from Hitler to sign the Tripartite Pact. In spite of German assurances to the contrary, this would almost certainly mean allowing Germany to use Jugoslavia's railway system to invade Greece. The Greek government had only the British to turn to for help, but Metaxas continued in his policy of not provoking Germany. He did not have Churchill's knowledge of Hitler's intentions.

On 10 January 1941 — the same day that Hitler decided to send a force to Libya to prop up the Italians and that X Air Corps, newly arrived in Sicily, attacked the aircraft-carrier HMS

Illustrious

—

Churchill received confirmation from intercepts of German signals decrypted at Bletchley Park, a source later known as Ultra, that the German build-up in Roumania formed a grave threat to Greece.

He promptly ordered draft contingency plans for the commitment of a British expeditionary force to the Greek mainland.

General Sir Archibald Wavell, the Commander-in-Chief in the Middle East, was less concerned.

During a flurry of signals between London and Cairo on 10 January, he argued that the Germans were basically engaged in 'a war of nerves'. Wavell felt his view was supported when General Heywood arrived from Athens the same day to say that the Greek government thought the Germans were just trying 'to warn both ourselves and [the] Russians off [the] Balkans'. But the Chiefs of Staff, following Churchill's directive, emphasized that his compliance was expected: 'His Majesty's Government have decided that it is essential to afford the Greeks the maximum possible assistance.'

Wavell flew in civilian clothes to Athens three days later for meetings with King George II of Greece, Metaxas and General Papagos. Metaxas wanted to prevent the British from sending a token force —

large enough to give the Germans an excuse to invade, but too small to stop them. General Papagos, guided by Metaxas, stated that 'it would be necessary for the Greek forces on the Bulgarian front to be immediately reinforced by nine divisions with corresponding air support'. Wavell replied that this was impossible. He could make available no more than two or three divisions. Metaxas said this was quite inadequate, and to send a small advance guard of artillery, as Wavell suggested, would only provide the Germans with a pretext for attack. Papagos later claimed to have argued that British divisions would in any case be better employed in North Africa.

Wavell reiterated his offer of an advance party just before flying back to Cairo. Having faithfully followed London's instructions, he was privately relieved that the Greeks persisted in refusing such aid, for General O'Connor's forces were advancing into Libya. The Chiefs of Staff in London and the War Cabinet 'all heaved a sigh of relief too, and so apparently did Churchill in private. Yet Churchill was conscious of broader political issues. Britain was constantly accused by German propaganda of letting down her allies and getting other countries to fight her wars for her. This latter jibe was galling at a time when 'Winston felt he must influence the Americans'.

Ultra intercepts continued to show that the German threat from Roumania was serious, and Churchill, whose view on the wisdom of sending an expeditionary force swung back and forth, refused to accept Wavell's argument that aid to Greece would be 'a dangerous half-measure'. His mind was fixed on the fact that Middle East command had 300,000 men on its ration strength, a figure which made him unable to believe that so few front-line troops were available. One of his War Cabinet staff later remarked that Churchill, although 'in some ways

au fait

with modern things', was 'much too ready to talk in terms of numbers of sabres and bayonets'.

Metaxas died of throat cancer on 29 January. German propaganda claimed that he had been poisoned at the dinner arranged in his honour by Wavell's ADC, Peter Coats, at the Hotel Grande Bretagne a fortnight before. The new Prime Minister, Alexandras Koryzis, was a banker, not a professional politician, and he lacked the robust certainties of his predecessor. His government quickly indicated that it was keen to have British assistance in any quantity.

Churchill, inspired by his sense of British history in which the island race had created alliances against the overbearing power of the time, took this as the signal to create a Balkan pact between Greece, Jugoslavia and Turkey. On his instructions, Anthony Eden, the Foreign Secretary, accompanied by Sir John Dill, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, left London for Cairo on 12

February — the day that Rommel arrived in Tripoli. General Wavell, on hearing of their visit, resigned himself to a heavy commitment to Greece, and assessed his fragmented forces.

Perhaps more than troops Wavell needed sound information. Unfortunately, Heywood was passing back unrealistically optimistic reports on the Greek army's capabilities, almost a repeat of his delusion in France. Blunt's assessment was far more sober. He knew that despite its magnificent resistance to the Italians, an effort which had taken its toll both of men and equipment, the Greek army stood little chance against German armoured and motorized divisions with overwhelming air support. And since Metaxas's death, underlying political tensions had begun to grow between the still dominant Metaxist officers and Venizelists whose careers had suffered under the dictatorship.

Heywood's version carried the day, largely because it satisfied Churchill's craving for positive news.

And there were still encouraging moments on the Albanian front to which he could point. On 13

February, the Greek offensive was renewed. The Cretan Division attacked north-westwards from Mount Trebesina, and again pushed the Italians back. Two days later they occupied the Medjigorani Pass and Mount Sen Deli. Heavy snowfalls soon brought operations to a virtual standstill. Several observers believed that without this setback

the Greeks would have captured the port of Valona, and this might have brought about the collapse of the Italian army. Others were less persuaded. The Greeks had neither the supplies nor the transport to sustain their advance.

The air war did not slacken in the face of often terrible flying conditions. On 28 February, the RAF

fought its most successful action of the campaign. Two squadrons, one of Hurricanes, the other of Gladiators, shot down twenty-seven Italian aircraft over the Albanian front in an hour and a half. This victory went some way towards mitigating Greek criticism of the RAF's refusal to deploy aircraft in close support of their troops, but at that stage of the war the RAF was attracting similar criticisms from the British Army: it considered itself purely a strategic arm.

At about this time, the Greeks received intelligence reports that the Italians had recovered sufficiently to plan a large counter-attack. This came in the second week of March with twelve Italian divisions deployed between the Apsos and Aöos rivers against the Greek front line of four divisions.

Mussolini, acutely aware that the German invasion being planned would put his army to shame, ordered his troops to attack 'at whatever cost'. During the week that followed, the Cretans in particular distinguished themselves by inflicting heavy losses. Their marksmanship, of which they were inordinately proud, was reputed to be the best in the Greek army. Within ten days, the great Italian counter-attack had petered out, but by then the situation in the Balkans, and indeed the whole of the Middle East, had changed. Mussolini's forces became a comparatively negligible consideration.

On 16 February, the first skirmish between British and German troops in North Africa took place near Sirte. Four days later Churchill acknowledged the dangers of dispersing forces, and signalled Eden, Dill and Wavell in Cairo: 'Do not consider yourselves obligated to a Greek enterprise if in your hearts you feel it would be only another Norwegian fiasco. But Eden, as the generals soon discovered, would not be diverted from his course.

Churchill, with his strong and at times over-emotional sense of loyalty to the Greeks and their King, longed to help whatever the risk. On the other hand, he still wanted clear advice from senior officers on the spot, yet had given Eden plenipotentiary powers 'in all matters diplomatic and military' before leaving London. This may well have convinced Dill and Wavell that they had no option but to support the line decided by the Foreign Secretary. Eden had clearly become enamoured with the idea of surprising the world with a grand alliance — the sort of

coup de thiätre

of which diplomats dreamed.

But, like Churchill, counting in 'sabres and bayonets', such illusions belonged to a past age.

Given the antiquated state of the Jugoslav and Turkish armies and air forces, a Balkan alliance could never have been anything more than a gesture. Wavell opposed Eden's attempt to draw the Turks into this scheme: it was the only time he spoke out firmly on the question. A Turkish defeat and German occupation of the Dardanelles would, he argued with justification, be disastrous. Fortunately, the Turks were clear-sighted enough not to be drawn into this deluded scheme. Aside from the German army massed in Roumania, they feared that Russia, their traditional enemy and still Hitler’s ally, might repeat the stab in the back which had been practised on Poland.

On 22 February Eden, accompanied by Dill, Wavell and Air Vice Marshal Longmore, the senior RAF

officer in the Middle East, flew to Athens. Before the first meeting at the Tatoi Palace, the Greek government, strongly encouraged by the King, declared its determination to resist the Germans whether the British came to their help or not. The British were impressed, even moved, by this courage. To their further approval, General Papagos conceded that a forward defence of Thrace and Eastern Macedonia was impracticable. He agreed that the bulk of Greek forces should be pulled back to the proposed Aliakmon line which ran from the northern face of Mount Olympus across and then up towards the Jugoslav border along the Vermion range. The safety of its left flank, just forward of the Monastir Gap, clearly depended on the Jugoslav army holding out against the Germans.

Eden, more excited than ever with the idea of a Balkan alliance, promised the Greeks 'formidable'

resources, bumping up the figures of the forces available which had been provided in the staff brief.

Colonel Freddie De Guingand, a member of the Middle East Joint Planning Staff, watched Wavell's dispirited support for the project with dismay. He, like many other officers later, found it hard to forgive him for not speaking out. After the meeting, De Guingand noted how Eden 'preened himself in front of the fire while his subordinates congratulated him on a diplomatic triumph.

This military view of events does not tally with that of the Foreign Office. Just before the main meeting, Sir Michael Palairet organized a private lunch to give Wavell a better idea of the issues involved, and to warn him that with the death of Metaxas, the King had the real power of decision. To the surprise of Harold Caccia, who was one of the four present, Wavell, 'normally rather a taciturn man, became quite loquacious'.

He began by saying, 'Well, the situation in Greece is not that different from Egypt', and went on to compare the defensive properties of the Greek mountain ranges to the Qattara Depression. 'That means it's not really relevant to ask how many divisions are needed, since only a certain number can be deployed.' This, like many rushes of false optimism which influenced the principal characters —