Criminal Poisoning: Investigational Guide for Law Enforcement, Toxicologists, Forensic Scientists, and Attorneys (10 page)

Authors: John H. Trestrail

2.4.2. The “Molecular Firepower” of Poisons

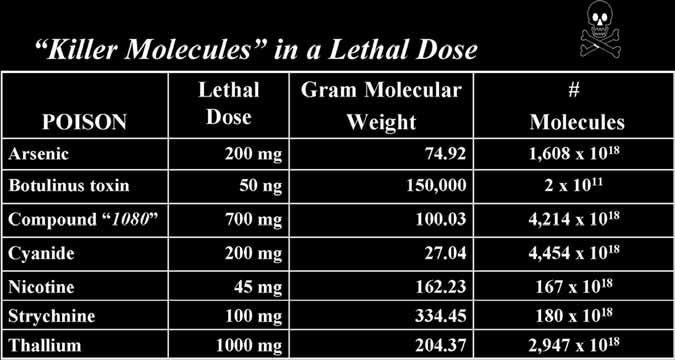

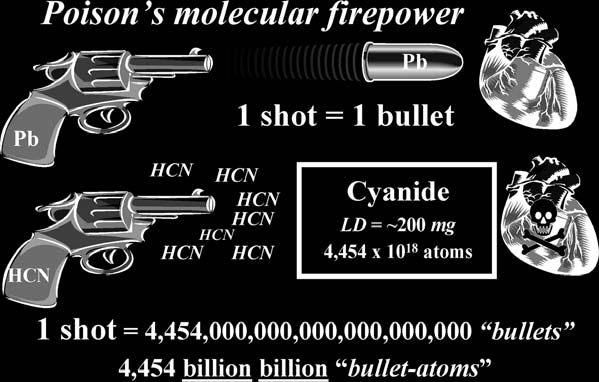

Poisons as weapons contain a lot of “molecular firepower.” When an individual aims a gun at another person and pulls the trigger, this in effect releases a single piece of lead that the offender hopes will produce a lethal effect on the intended target, by disrupting body tissue and vital organs, which will lead to the target’s death. However, with a poison, one does not unleash a single bullet, but literally millions of “chemical bullets,” to do their lethal business. How many chemical molecules are contained in a lethal dose? With an elementary knowledge of chemical principles, one can easily calculate the number of “killer molecules/atoms” contained in a lethal dose of any substance. This calculation is based on what is known as Avogadro’s number, which states that there are 6.02214199 × 1023 molecules, or atoms, per gram molecular weight of any substance. If one then takes the MLD of a poison, how many atoms or molecules are contained therein can be easily calculated (

see

Fig. 2-7

). In scientific notation, 10

18 is a number representing 1 billion billion. Thus, cyanide contains 4454 billion billion atoms in a lethal dose of

Types of Poisons

39

Figure 2-7

200 mg. This represents a great deal of chemical firepower for just a few cents’ worth of a substance. In fact, at a cost of $14/lb (454 g) for cyanide, this amount of chemical represents 2270 human lethal doses, or 0.6 cents per lethal dose, or 1.7 lethal doses for a cost of 1 cent. In reality, then, a poison is much cheaper than a bullet. A 9-mm round costs approx 40 cents; for the same price, one can purchase almost 68 lethal doses of cyanide (

see Fig. 2-8).

Over the last several years, a rather interesting number of murders have occurred in China with the use of a rodenticide called Dushuqiang, pronounced “doo-shoo-Chiang,” which is chemically known as tetramethyenedisulfotetra-mine. Having a human lethal dose of only 7–10 mg, in the weight of a nickel, this substance would contain about 740 lethal doses! The onset of symptoms—seizures and coma—after administration of this poison is 30 min to 3 h. There have been so many murders and tamperings in China with this material that the Chinese government has outlawed its production, sale, and possession. In 2003, the Chinese government seized 105 tons (92,281 kg) of this rodenticide, which amounted to a potential 13.6 billion lethal doses! Can we expect to see this rodenticide in the United States? In 2002, there was an accidental exposure in this country from this rodenticide, which had been illegally imported (“Poisoning,” 2003).

2.5. Elements of Poisoning Investigations

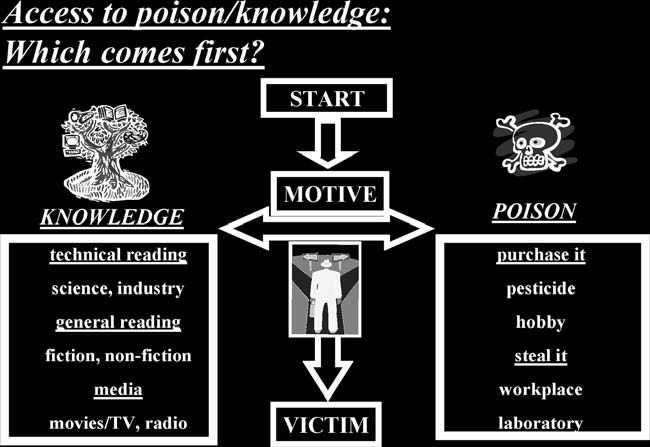

When examining poisoning cases, it is very helpful to look at the possible sources not only for the poison, but also the knowledge on how to use the poison.

40

Criminal Poisoning

Figure 2-8

2.5.1. Access

At this point in time it is not known which comes first for a poisoner: the knowledge about the poison, or the possession of the poison itself. However, one can hypothesize that more than likely the cunning poisoner seeks out a poison that will fulfill the characteristics he or she wishes. Let us assume, then, that the knowledge comes first (

see

Fig. 2-9

).

2.5.2. Knowledge

Where would one be able to obtain toxicological information? The criminal investigator should consider a number of resources that a poisoner could utilize that would provide valuable information to plan his or her crime. Among these information resources are the following:

1.

Educational background:

A poisoner can obtain much information from professional training in biology, chemistry, pharmacology, and/or medicine.

2.

Printed media:

Criminal investigators need to look at the suspect’s access to books (both fiction and nonfiction), chemical manuals, magazines, and newspapers for materials relating to poisons or crimes in which poisoning has played a part. Investigators should be especially aware of the availability of “underground”

press materials relating to the use of poisons. The following three such poison references are currently available for purchase:

a.

Assorted Nasties

, by David Harber, Desert Publications, El Dorado, AR, 1993

b.

Silent Death

, by Uncle Fester, Loompanics Unlimited, Port Townsend, WA, 1989, 1997 (2nd ed)

Types of Poisons

41

Figure 2-9

c.

The Poisoner’s Handbook,

by Maxwell Hutchkinson, Loompanics Unlimited, Port Townsend, WA, 1988

On the Internet, any individual can easily find these manuals for sale, in which there is an enormous amount of information on poisons—their procurement, production, administration, and lethal dose—as well as how to avoid detection from crime committed using them. It is important to note, however, that protection of these types of reference manuals by the First Amendment to the US Constitution has now been condemned by the court decision

Rice vs. Paladin Press

,

87–1325

.

If criminal investigators find any of these materials during a search, their suspicions should be aroused immediately.

3.

Visual media:

Criminal poisonings are often examples of life imitating art. Investigators need to look for access to movies and television materials relating to poisons or crimes in which poisoning has played a part.

4.

The workplace:

Labels, manuals, material safety data sheets, or other materials dealing with chemicals should be investigated.

5.

Computers:

The amount of information that is available to computer users via the Internet or the World Wide Web is vast. Investigators should consider the possibility of a computer link for information on poisons, or crimes in which poisoning played a part.

6.

Word of mouth:

Although it is unusual for an offender to talk openly about poisons and their procurement, some cases have relied heavily on the testimony of individuals who have had conversations with the suspect on such matters.

42

Criminal Poisoning

2.5.3. Sources

Once the potential poisoner has knowledge about the poisonous weapon he or she has chosen, where does he or she go to obtain the material itself?

Criminal investigators should consider some of these sources: 1.

Laboratories:

The suspect may have access to chemical substances found in laboratories in industrial, medical, or educational facilities.

2.

Hobbies:

The suspect may have hobbies that could provide poisonous substances, such as photography, jewelry manufacturing, or mineralogy.

3.

“Underground” catalogs

: Unbelievably, there are some individuals who collect poisons and poison bottles, like others collect guns or knives. There was at least one catalog available for such individuals,

JLF

, based in Indiana. This catalog of “poisonous nonconsumables,” which contained a long and detailed disclaimer, allowed one to purchase, e.g., toxic dried plants and fungi, and even stated in one issue that cobra venom would be “coming soon.” In 2002, the producer of this catalog was convicted of eight counts of violation of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and the Controlled Substances Act.

4.

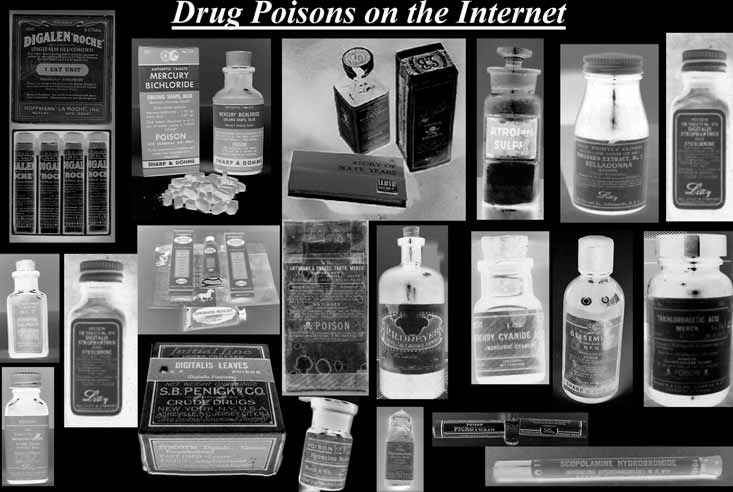

Antique drug/chemical bottles:

Here is a source of poisons that is often overlooked by investigators. Surprisingly, one can purchase antique chemical bottles sometimes with their lethal contents still intact. These items can be obtained from flea markets, Internet auctions, or bottle collectors, and more than likely there is no paper trail of the purchase that leads to the offender.

2.5.3.1. SELLING ANTIQUE CHEMICALS CAN CAUSE MODERN TROUBLES

To reduce any potential for unwanted toxicological incidents, the sale and distribution of poisons, legend drugs, and hazardous materials is limited by law to licensed professionals. However, some of these items have found their way into the hands of individuals not licensed to possess or sell such materials. At antique shows and flea markets around the country, and over the Internet via auctions, dealers have been found selling antique drug and chemical bottles that still contain toxic contents, including arsenic, hemlock, mercuric chloride, phenobarbital (a controlled substance), sodium fluoride, and strychnine. How do these individuals come into possession of these drug and chemical containers that still hold hazardous material? When queried, most dealers have responded that their sources have been the stocks of old pharmacies and medical offices. They also have stated their belief that the container’s contents are now inert owing to the extreme age of the product, a belief that, for the most part, is clearly and dangerously erroneous. The compounds of arsenic, e.g., are as old as the earth itself and are as toxic today as when they were first

formed billions of years ago.

Figs. 2-10

and

2-11

provide just a few examples of potentially lethal drugs and chemicals that were sold on an Internet auction site as antique poison bottles (contents included!).

Types of Poisons

43

Figure 2-10

2.5.3.2. THE PROBLEMS THAT ANTIQUE POISONS PRESENT

A poison by any other name is still as dangerous, and the toxicological implications associated with the sale of antique hazardous chemicals focus on at least three major problem areas.

2.5.3.2.1. Antique Poisons in the Home

The presence of extremely hazardous antique poisonous substances in the home presents a clear and present danger for accidental and suicidal poisonings. If the collector of antique containers maintains a collection with their contents, then this presents an enormous risk in the home. One case in point involved the son of a pharmacist, who, while in a suicidal frame of mind, packed and swallowed capsules filled with sodium arsenite from his father’s collection of antique bottles. The physiological impact of this heavy metal poison almost cost him his life, and the damage to his nervous system was such that even after months of hospitalization and rehabilitation the arsenic-induced peripheral neuropathies could not be totally reversed. The father will probably always regret that this poison was in his home, readily available to his emotionally distressed son.