Criminal Poisoning: Investigational Guide for Law Enforcement, Toxicologists, Forensic Scientists, and Attorneys (11 page)

Authors: John H. Trestrail

44

Criminal Poisoning

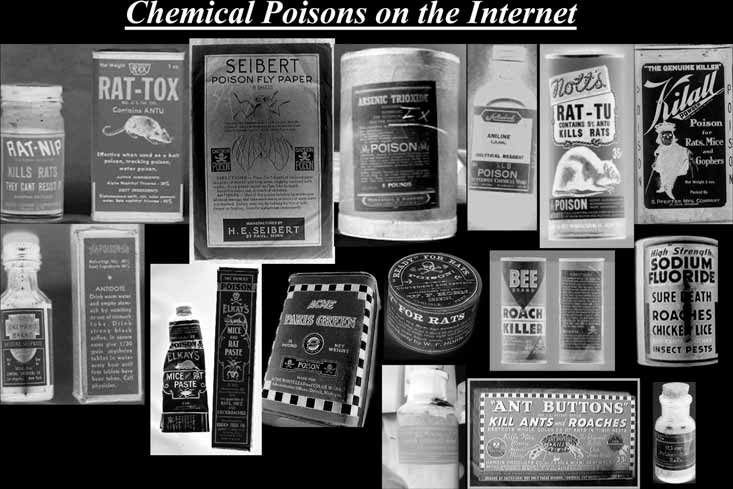

Figure 2-11

2.5.3.2.2. Procurement of Poison

With Homicidal or Tampering Intent

It is always of concern to society and to law enforcement personnel that the availability of poisons with a potential for homicidal or tampering use be carefully controlled. Thus, the sale of such substances must always be carefully documented in such a manner that proof of transfer of owner-ship is always maintained. By law, pharmacies are required to maintain a “poison register,” to record the sale of any poisonous materials. These registers of sales include the purchase date, the name of the buyer, the buyer’s address, the poison sold, the amount sold, and the intended use.

Selling such poisonous substances without a paper trail could allow homicidal poisoners or tamperers to obtain chemical weapons with no traceable evidence.

2.5.3.2.3. Improper Disposal of Extremely Hazardous Substances In accordance with Title III of the Superfund Amendments Reauthorization Act [P.L. 99-499], it is illegal for any individual or business to dispose of Types of Poisons

45

“extremely hazardous substances” (EHS) unless done in a manner consistent with local, state, and federal guidelines. Most knowledgeable businesses will contract with a licensed toxic disposal firm to remove and properly dispose of their unwanted hazardous items. It is also important to note that even if the service of a disposal firm is used for hazardous substances, the original owner is still ultimately responsible for any environmental risk or contamination that may result from the materials. This responsibility cannot be transferred by sale or disposal.

It is important for pharmacists, physicians, and other health professionals to realize that selling their old chemical substances to an individual is not consistent with published guidelines, and that the health professional will ultimately be held legally liable for any toxicological problems that might arise. It is also illegal to dispose of these substances in domestic refuse, or to dump them in such a manner that could lead to contamination of soil or water environments.

2.5.3.3. THE SOLUTION

The solution to keeping toxic chemicals out of the hands of the lay public is quite simple. Antique bottles containing hazardous contents must never be sold. The hazardous contents must be carefully removed and disposed of in a manner that is consistent with local, state, and federal legal guidelines. Detailed records must be maintained that document proper disposal of any hazardous chemical substance. Health and law enforcement professionals must remain vigilant regarding the sale of these chemicals to unlicensed individuals and must clearly and emphatically state to the sellers the dangers of this practice.

Any seller who refuses to withdraw these materials from sale should be immediately reported to the local office of the Food and Drug Administration, Consumer Products Safety Commission, and the Environmental Protection Agency.

2.6. REFERENCES

Deichman WB, Henschler D, Keil G: What is there that is not poison? A study of the Third Defense

by Paracelsus.

Arch Toxicol

1986;58:207–213.

Latham PM: htty://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/p/peterlatha204591.html

Meloy JR, McEllistrem JE: Bombing and psychopathy: an investigative review.

J Forensic Sci

1998;43(3):556–562.

Poisoning by an illegally imported Chinese rodenticide containing Tetramethylenedisulfotetramine—New York City, 2002.

MMWR Weekly

2003;52(10):199–201.

The Sloane-Dorland Annotated Medical-Legal Dictionary

. West Publishing, New York, 1987.

Stedman’s Medical Dictionary, 26th ed. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD, 1995.

46

Criminal Poisoning

Taylor AS:

On Poisons in Relation to Medical Jurisprudence and Medicine,

2nd ed. John Churchill, London, 1859.

Watkins v National Elec. Products Corp., C.C.A. Pa., 165, F.2d 980, 982.

2.7. SUGGESTED READING

Dart RC, Caravati EM, McGuigan MA, et al:

Medical Toxicology

, 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2004.

Farrell M:

Poisons and Poisoners: An Encyclopedia of Homicidal Poisonings.

Robert Hale, London, 1992.

Ferner RF:

Forensic Pharmacology: Medicines, Mayhem, and Malpractice

. Oxford University Press, New York, 1996.

Ford MD, Delaney KA, Ling LJ, et al:

Clinical Toxicology

. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2001.

Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, Lewin NA,

et al.

Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies,

7th ed. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2002.

Haddad LM, Shannon MW, Winchester JF:

Clinical Management of Poisoning and Drug Overdose,

3rd ed. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1998.

Thompson CJS:

Poison Mysteries in History, Romance and Crime.

J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1924.

Poisoners

47

Poisoners

“When you consider what chance women have to poison their husbands, it’s a wonder there isn’t more of it done.”—(Frank McKinney “Kin”

Hubbard, http://en.thinkexist.com/quotations/when_you_consider_what_

a_chance...)

As stated in the preface to this work, the poisoner has remained shrouded in mystery for centuries. Let us now examine what we know about the poisoner as an offender, and what we think we know about the poisoner.

3.1. TYPES OF POISONERS

One way to look at the motivation of a poisoner is to study how the victim is selected: some poisoners choose a specific individual, whereas others choose someone at random. The motives of these two types of poisoners are very different.

I have developed the following method of classification of poisoners based on victim specificity and degree of planning involved. There are two major groups: those who target a specific victim and those who choose a victim at random (

see

Fig. 3-1

). Each group has two subgroups based on the

speed with which the crime is planned and then carried out.

3.1.1. Type S: Specific Victim Is Targeted

Motives for the Type S group of poisoners include money, elimination, jealousy, revenge, and political ambition.

From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

47

48

Criminal Poisoning

Figure 3-1

3.1.1.1. SUBGROUP S: SLOWLY PLANNED POISONING

WITH A CAREFULLY SELECTED POISON

An example of the Subgroup S type of poisoner would be a woman angry with her husband who goes to the library, reads about a particular poison, procures the chemical, and decides the best manner of administration to the victim. Type S/S = Specific/Slow.

3.1.1.2. SUBGROUP Q: A QUICKLY PLANNED POISONING

A crime committed by someone in Subgroup Q is done spontaneously with a poison selected as a weapon of opportunity. An example of this type of poisoner would be a woman angry with her husband who quickly takes a can of herbicide from storage and adds some to his food while preparing a meal.

Type S/Q = Specific/Quick.

3.1.2. Type R: A Random Victim Is Targeted

Motives for the Type R group of poisoners include ego, the desire to tamper, boredom, and sadism.

3.1.2.1. SUBGROUP S: A SLOWLY PLANNED POISONING

WITH A CAREFULLY SELECTED POISON

An example of the Subgroup S type of poisoner would be a tamperer intent on industrial blackmail who adulterates a food/drug with a carefully Poisoners

49

selected poisonous substance. This group would also include terrorists. Type R/S = Random/Slow.

3.1.2.2. SUBGROUP Q: A QUICKLY PLANNED POISONING

A crime committed by someone in the Subgroup Q is spontaneously done with a poison selected as a weapon of opportunity. An example of this type of poisoner would be an employee upset with his or her employer who quickly picks up a toxic substance and adulterates a batch of a consumer product (e.g., food, drug, cosmetic) to which the poisoner has access. Type R/Q =

Random/Quick.

Although we may think we have been able to classify poisoners, we must remember to be aware of the “camouflaged” poisoner. In this situation, a poisoner gives the appearance of being a Type R but is in reality a Type S.

An example of this type of poisoner would be an offender who poisons her spouse by tampering with his medication and then places similar tampered containers in a retail store to make the death of the victim appear to be random. There are various recorded cases of this type of poisoner at work. Among the more infamous cases, listed chronologically, are as follows: •

Christiana Edmunds (Brighton, UK, 1871):

Poisoned chocolates in a confec-tioner’s shop with strychnine, and one innocent child became a random victim.

Her specific target was the wife of the man who thwarted her affection.

•

Ronald Clark O’Bryan (Pasadena, Texas, 1974):

Poisoned Halloween candy with cyanide. His son, whom he killed to collect a life insurance premium, was the specific victim. He was also convicted of three attempts to murder other neighborhood children. Poisoning the other children had been part of his plan in order to make the crime appear to be the actions of a deranged tamperer.

•

Stella Maudine Nickell (Auburn, Washington, 1986):

Poisoned Excedrin® capsules with cyanide to cover up the specific murder of her husband for insurance money. One random victim died.

•

Joseph Meling (Tumwater, Washington, 1991):

Poisoned Sudafed 12-Hour® capsules with cyanide to cover up the specific murder attempt on his wife. One random victim died.

•

Paul Agutter (Athelstaneford, Scotland, 1994):

Poisoned tonic water with atropine to cover up the specific murder attempt on his wife. Eight victims suffered from atropine intoxication as a result of his tampering, but there were no deaths in this case.

Investigators should remember, from these cases, always to question whether an apparent product tampering might actually be an attempt to cover up a specific homicide by throwing their investigation off the correct track.

50

Criminal Poisoning

3.2. MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT POISONERS

It is important to correct some common myths about poisons and poisoners that exist in the minds of the general population. Among these myths is that most poisoners are female. In actuality, the majority of poisoners who have been detected have been male. The words “have been detected” are very important. This could lead one to speculate that females are more successful at escaping detection. Certainly they have a greater opportunity to invade the “security zone” of the victim, for it is typically the female who takes care of the sick, prepares the meals, and cleans the house.

Another common myth is that for every poison there is an emergency antidote. (It should also be emphasized here that the proper word for this type of drug is “antidote,” not “anecdote,” which is sometimes used erroneously.) In reality, there are currently only five drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration that can make a life-or-death difference in the poisoning emergency. These antidotes are atropine (for organophosphate insecticides, nerve agents), Cyanide Antidote Package® (for cyanide intoxication), epinephrine (for allergic shock), naloxone (for opiates and narcotics), and oxygen (for carbon monoxide).

The last myth, and a question very commonly asked, is: Does a perfect undetectable poison exist? The answer to this question could be yes or no, depending on how one describes the word “undetectable.” The answer should be no if one considers that if there was such an undetectable substance how would one ever know it existed? If it has a name, someone must have detected it at least once to name it, and, therefore, anything with a name is theoreti-cally detectable. However, the answer could be yes if one means by “undetectable” that the chance the poison would be routinely seen in a toxicological analysis is slim. If poisoning is suspected, and the analytical experts are given proper guidelines, almost every toxic chemical can be identified. However, if there are no guidelines to assist them, it is rather like looking for a molecular needle in a chemical haystack. If the substance is not one screened for in their normal substance panels, it will very likely go “undetected.” The problem is not the perfection of the poison, but the imperfection of the analytical process. Here it should also be emphasized that a “negative” toxicological screen does not mean that there is no poison in the specimen but, rather, that all the poisons routinely tested for in the analysis are absent. Other, more exotic poisonous compounds could remain undetected.