Crows (11 page)

Authors: Candace Savage

The idea for a raven IQ test came to Heinrich serendipitously, from an article in a children’s magazine. Tie a lump of food to a string, the author suggested, suspend it under a perch, and see which birds are clever enough to get it. This experiment required such minimal effort (no carcasses to lug) that Heinrich decided to try it on his backyard research colony of captive ravens. The prize would be a lump of leathery old salami, suspended in midair. The only way to get it was to pull it up, something these ravens had never done; Heinrich was almost certain they would be flummoxed. So imagine his astonishment when one raven first cautiously checked out the setup and then confidently proceeded to pull up loop after loop of string, anchoring each with his foot, until he succeeded in hoisting up the treat.

In subsequent trials, a few ravens proved unable to solve the problem, an indication that playing string games is not instinctive. But others—perhaps the Einsteins of the raven race—obtained the meat within thirty seconds of

touching the apparatus. Even more amazing in Heinrich’s eyes was the fact that the successful birds never flew away with their salami-on-a-rope, as they would inevitably have done with any ordinary morsel. It was as if they understood, without even having to try, that the food would be ripped out of their bills if they attempted to fly. “The significance of the remarkable behavior of

not

flying off was that it was a

new

behavior that was acquired without any learning trials,” Heinrich says. “They acted as though they had already done the trials. The simplest hypothesis is that they had—in their heads.”

touching the apparatus. Even more amazing in Heinrich’s eyes was the fact that the successful birds never flew away with their salami-on-a-rope, as they would inevitably have done with any ordinary morsel. It was as if they understood, without even having to try, that the food would be ripped out of their bills if they attempted to fly. “The significance of the remarkable behavior of

not

flying off was that it was a

new

behavior that was acquired without any learning trials,” Heinrich says. “They acted as though they had already done the trials. The simplest hypothesis is that they had—in their heads.”

Heinrich’s results strongly suggest that ravens are able to think before they act. But there is a big difference between understanding relatively simple physical concepts—meat tied down—and assessing subtle and ever-changing social relationships. And so the mystery persists: do ravens use their smarts to outsmart one another?

CACHE AND CARRYAs a verb, the word “raven” means “devour greedily,” and that is exactly what a mob of ravens does when it falls upon a carcass. Any fellow feeling that existed among gang members when they assembled quickly dissolves into a

sauve qui peut

of unabashed self-interest. Each bird attempts to monopolize as much of the meat as it can by tearing off extra bits and hiding them. There is a flurry of rustling wings as ravens come and go, throat pouches bulging with food and bloody scraps of flesh dangling from their bills. Every tidbit is cached separately, often in snow or dirt, and only the bird that hid the food knows where to find it—with one critical exception. If another raven happens to be watching, it too will mentally map the spot, intent on sneaking back and stealing the reward.

sauve qui peut

of unabashed self-interest. Each bird attempts to monopolize as much of the meat as it can by tearing off extra bits and hiding them. There is a flurry of rustling wings as ravens come and go, throat pouches bulging with food and bloody scraps of flesh dangling from their bills. Every tidbit is cached separately, often in snow or dirt, and only the bird that hid the food knows where to find it—with one critical exception. If another raven happens to be watching, it too will mentally map the spot, intent on sneaking back and stealing the reward.

➣

Nature red in tooth and claw—a raven pecks at a moose that was injured by a pack of wolves in Denali National Park, Alaska.

Nature red in tooth and claw—a raven pecks at a moose that was injured by a pack of wolves in Denali National Park, Alaska.

SILVERSPOT’S TREASURES

FROM

WILD ANIMALS I HAVE KNOWN,

BY ERNEST THOMPSON SETON, 1898

WILD ANIMALS I HAVE KNOWN,

BY ERNEST THOMPSON SETON, 1898

O

ne day while watching I saw a crow crossing the Don Valley [in Toronto] with something white in his beak. He flew to the mouth of the Rosedale Brook, then took a short flight to the Beaver Elm. There he dropped the white object, and looking about gave me a chance to recognize my old friend Silverspot [an old crow that could be recognized by a white patch on the side of his face]. After a minute he picked up the white thing—a shell—and walked over past the spring, and here, among the docks and the skunk-cabbages, he unearthed a pile of shells and other white, shiny things. He spread them out in the sun, turned them over, lifted them one by one in his beak, dropped them, nesting on them as though they were eggs, toyed with them and gloated over them like a miser. This was his hobby, his weakness.... His pleasure in them was very real, and after half an hour he covered them all, including the new one, with earth and leaves, and flew off. I went at once to the spot and examined the hoard; there was about a hatful in all, chiefly white pebbles, clamshells, and some bits of tin, but there was also the handle of a china cup, which must have been the gem of the collection. That was the last time I saw them. Silverspot knew that I had found his treasures, and he removed them at once; where I never knew.

ne day while watching I saw a crow crossing the Don Valley [in Toronto] with something white in his beak. He flew to the mouth of the Rosedale Brook, then took a short flight to the Beaver Elm. There he dropped the white object, and looking about gave me a chance to recognize my old friend Silverspot [an old crow that could be recognized by a white patch on the side of his face]. After a minute he picked up the white thing—a shell—and walked over past the spring, and here, among the docks and the skunk-cabbages, he unearthed a pile of shells and other white, shiny things. He spread them out in the sun, turned them over, lifted them one by one in his beak, dropped them, nesting on them as though they were eggs, toyed with them and gloated over them like a miser. This was his hobby, his weakness.... His pleasure in them was very real, and after half an hour he covered them all, including the new one, with earth and leaves, and flew off. I went at once to the spot and examined the hoard; there was about a hatful in all, chiefly white pebbles, clamshells, and some bits of tin, but there was also the handle of a china cup, which must have been the gem of the collection. That was the last time I saw them. Silverspot knew that I had found his treasures, and he removed them at once; where I never knew.

This interaction, in which the parties stand to profit by deceiving one another, provides a perfect natural laboratory for studying the mind of the trickster. If ravens really do attempt to outwit one another in this game of hide-and-seek, then both parties should be expected to behave strategically. On one side of the equation, for instance, a bird with food to hide might fly away from the crowd before burying its treasure or slip behind a boulder, where it knows it can’t be observed. And if, despite these maneuvers, it happens to catch another raven looking, it should dig up its cache and relocate it to a new and more secure location. Sure enough, in experiments by Heinrich and his colleagues—notably, Austrian zoologist Thomas Bugnyar—caching ravens have been found to employ all these tactics. What’s more, ravens have also been known to make “false caches” by going through all the motions of caching in front of other birds and then, when the would-be thieves rush in, carrying the food away to hide it in private.

On the other side of the equation, the larcenous observers have a trick or two of their own. Rather than rushing up to see what the cacher is doing, they act casually and keep a little distance apart, as if they had no interest in what was going on. All the while, however, they are surreptitiously maneuvering to keep their sightlines clear and pinpoint the location of the hidden food. And even after the cache has been completed and the cacher leaves (with many an anxious backward glance), the observers maintain their undercover surveillance. A minute passes, two minutes. Finally, when the cacher seems to have cleared the area, the would-be thieves dash in, in an attempt to empty the cache before its rightful owner can come rushing back.

➣

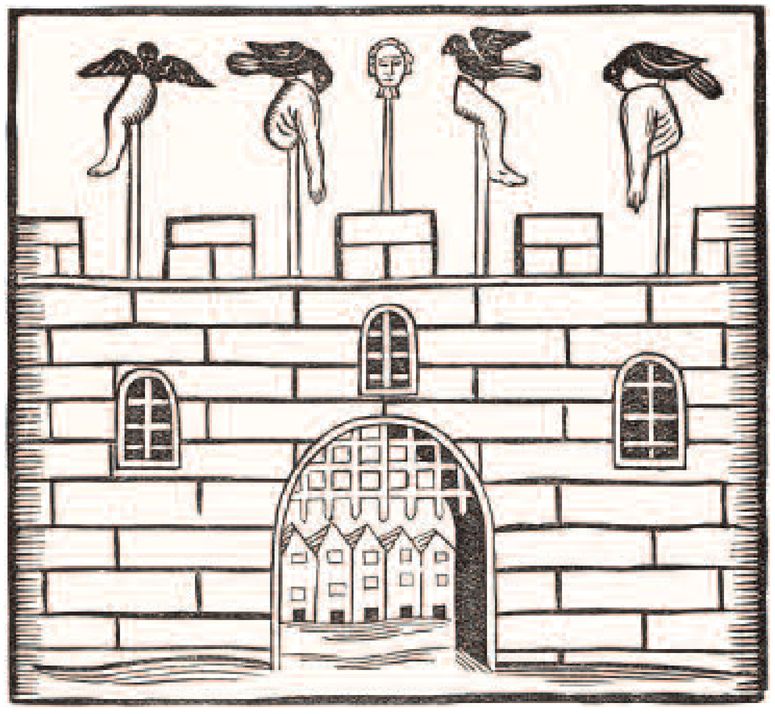

Crows feast on the remains of the unfortunate John Stevens, who in 1635 was hanged, drawn, and quartered for treason.

Crows feast on the remains of the unfortunate John Stevens, who in 1635 was hanged, drawn, and quartered for treason.

When Thomas Bugnyar published these findings in

Animal Behaviour

in 2002, he suggested that, based on his observations of caching both in the laboratory and the field, ravens appear to mislead each other intentionally. Yet he still couldn’t entirely exclude the possibility that the birds were on autopilot, acting out a complex set of genetic instructions. Then along came a raven named Hugin.

Animal Behaviour

in 2002, he suggested that, based on his observations of caching both in the laboratory and the field, ravens appear to mislead each other intentionally. Yet he still couldn’t entirely exclude the possibility that the birds were on autopilot, acting out a complex set of genetic instructions. Then along came a raven named Hugin.

RAVEN OPENS THE BOX

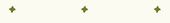

Celestial Ravens,

Celestial Ravens,by Cape Dorset artist Kenojuak Ashevak, 2003.

PARAPHRASED FROM A TEXT PUBLISHED ONLINE BY THE ALASKA NATIVE KNOWLEDGE NETWORK, 1995

I

n the beginning, the elders of southwestern Alaska tell us, the world was in darkness. The most powerful being on Earth was Raven. One day, he learned of a beautiful young woman who lived with her father, a great chief, on the banks of the Nass River. She possessed the sun, the moon, and the stars and kept them closely guarded in carved cedar boxes.

n the beginning, the elders of southwestern Alaska tell us, the world was in darkness. The most powerful being on Earth was Raven. One day, he learned of a beautiful young woman who lived with her father, a great chief, on the banks of the Nass River. She possessed the sun, the moon, and the stars and kept them closely guarded in carved cedar boxes.

The only way to steal these treasures, Raven knew, was to trick the woman and her father. So he turned himself into a hemlock needle, fell into the woman’s cup, and entered her body with a drink of water. Soon she bore a son, whom the chief dearly loved. When the boy (who was really Raven) grew a little older, he pleaded and cried for the box containing the moon and stars. As soon as his grandfather gave them to him, Raven threw them up the smokehole and they scattered across the sky. Although his grandfather was unhappy, he loved the boy too much to punish him for what he had done.

Soon the boy began crying for the other box—the one containing the sun—and again his grandfather gave it to him. Raven played with the box for a long time. Then suddenly he turned himself back into a bird and flew up through the smokehole and out of the house. After a long time, he heard people below him in the darkness.

“Would you like to have light?” he asked them. Then he opened the beautiful box and let sunlight into the world. The people were so frightened that they fled to every corner of the Earth, and that is why Raven’s people are everywhere.

Other books

Before You Go (YA Romance) by James, Ella

When Sparks Fly by Autumn Dawn

Cold Feet by Amy FitzHenry

Gator Aide by Jessica Speart

The Seer and the Scribe by G.M. Dyrek

En Silencio by Frank Schätzing

05. Children of Flux and Anchor by Jack L Chalker

Mystery in the Minster by Susanna Gregory

The Secret Lover by London, Julia