Crows (12 page)

Authors: Candace Savage

In Aesop’s fable, a “helpful” crow taught his fellow to break a shell by dropping it on a rock and then swooped down to claim the food for himself.

In Aesop’s fable, a “helpful” crow taught his fellow to break a shell by dropping it on a rock and then swooped down to claim the food for himself.Named for one of the all-knowing birds that served the Norse gods in Valhalla, Hugin was a perfectly ordinary six-year-old male that had been bred in a zoo and raised, with a companion named Munin and a couple of other birds, in an aviary at the Konrad Lorenz Research Station in Grünau, Austria. As part of an investigation of social learning, the four ravens were presented with three clusters of film canisters, each marked with yellow, red, or blue. Every day, a different one of the color-coded sets of containers was baited with bits of cheese. The idea was to present the ravens with a problem that would take them some time to solve so that the researchers could make observations at their leisure.

In the event, however, Hugin figured out the rule on the first morning of the trials; after finding one empty box in a cluster, he would move on to the next group until he located the boxes that contained bait. His companion Munin, by contrast, couldn’t even be bothered to look. Instead, as the dominant bird in a group, he preferred to bide his time until Hugin found the

food; then he would muscle in and gobble up one or more of the tasty tidbits. With Munin now hanging around the food source, poor Hugin was out of luck. The more lids he flipped and the more cheese he found, the more Munin benefited.

food; then he would muscle in and gobble up one or more of the tasty tidbits. With Munin now hanging around the food source, poor Hugin was out of luck. The more lids he flipped and the more cheese he found, the more Munin benefited.

Socially subordinate though he was, Hugin was no pushover. On the first afternoon of the experiment, he came up with a countermove. When Munin began to press in on him, Hugin would interrupt his foraging, fly over to one of the unrewarded clusters, and start opening empty boxes. He kept at it, opening and opening, until Munin came to join him; then, as soon as he saw his rival nosing around the wrong cluster, Hugin would dash back to the rewarded boxes and take advantage of his head start to grab a few extra morsels. This behavior went on for a week, until Munin caught on to the ruse and refused to be led astray. Having lost his advantage, Hugin threw a tantrum—“He started throwing containers around,” Bugnyar reports—but he soon regained his composure and learned to compensate for Munin’s thefts by stealing from the other ravens in the experiment.

Hugin the raven had told a fib and, until he was found out, had gained a tangible personal advantage through misrepresentation. This shady behavior satisfies the definition of “tactical,” or intentional, deception and admits the raven to an exclusive club of sociable liars that in the past has included only humans and our close primate relatives. Think of it as the survival of the trickiest.

{ FOUR }

Fellow

FEELING

FEELING

T

THE ONLY DISTINCTION left standing between other animals and us is our unique facility with language. All the other accolades that, over the years, we have claimed for our own species have eventually had to be shared, first with the higher primates and now with the “feathered apes” of the genus

Corvus.

Not only has Man the Toolmaker been forced to make room on his pedestal for orangutans and chimps, but he has also had to accept the crow that is perched on top of his head. By the same token, human social interactions have turned out to be remarkably similar to those of many

primates and corvids. And if Hugin’s high jinks are anything to go by, it seems that

Homo sapiens sapiens

cannot even claim to be altogether exceptional in the arts of deceit.

Yet the ability to string syllables together in a meaningful, grammatical order—to catch the world in a net of words—continues to stand as an exceptional and quintessentially human achievement. Although you may one day see a crow using a simple tool or a raven playing a trick, you are never going to find a bird with its beak in a book.

This distinction is important, and it reigns unchallenged, so far, though it too has begun to blur around the edges. Without questioning the central premise of human uniqueness, researchers have been trying to understand the way that language is learned, through the

da-da, ma-ma

babble of babyhood. Our close primate relatives do not burble like this—they can grunt perfectly from day one—but crows and other songbirds are much more like us in this regard. As youngsters, songbirds have to practice their vocalizations by listening to other members of their species, without whose example they cannot learn to sing, and then producing outbursts of burbling, free-form warbling known as “plastic song” and “subsong.” A young crow, for example, can sometimes be found all alone on a branch, completely self-absorbed, uttering a liquid, rambling medley of soft caws, coos, clicks, rattles, and grating, rusty-gate sounds. To hear it, you might think you had come upon an avian Ella Fitzgerald; the music expresses the same kind of lyricism and joie de vivre.

da-da, ma-ma

babble of babyhood. Our close primate relatives do not burble like this—they can grunt perfectly from day one—but crows and other songbirds are much more like us in this regard. As youngsters, songbirds have to practice their vocalizations by listening to other members of their species, without whose example they cannot learn to sing, and then producing outbursts of burbling, free-form warbling known as “plastic song” and “subsong.” A young crow, for example, can sometimes be found all alone on a branch, completely self-absorbed, uttering a liquid, rambling medley of soft caws, coos, clicks, rattles, and grating, rusty-gate sounds. To hear it, you might think you had come upon an avian Ella Fitzgerald; the music expresses the same kind of lyricism and joie de vivre.

Improvisation is the hallmark of crow song. According to zoologist and crow musicologist Eleanor Brown, every phrase in these muttered arias is original. Not only are the song elements strung together freely in varying patterns—four coos, followed by two grating rattles, then a caw/rattle hybrid, followed by five caws, or, another time, a single caw followed by seven short coos—but the elements in the series are also modulated. In a sequence of five caws, for example, each note differs from the next in both pitch and duration. And these changeful incantations can spin on for an hour or more as the bird preens its feathers, manipulates objects, stretches, looks around, and socializes with its companions. Within a family grouping, siblings often vocalize together, either by chorusing back and forth or by singing in unison, uttering the same or very similar sounds at the same moment. Sometimes these pairs of crooners cozy up together, a few inches apart, and synchronize both their songs and their gestures.

➣

In this drawing by American illustrator Louis Rhead, the great wizard Merlin consults two sources of wisdom, book and bird.

In this drawing by American illustrator Louis Rhead, the great wizard Merlin consults two sources of wisdom, book and bird.

What these duos are doing, Brown argues, is harmonizing their songs as a mark of friendship, or social affiliation. Each family of crows that she has studied has its own vocabulary of sounds, some of which—long and short caws and various rattles—they share with other groups, but many of which are idiosyncratic. One family of four American crows, for example, produced a “kek” caw and a high rattle that none of the other crows in the neighborhood used. At least some of their distinctive syllables were learned. In particular, a fledgling known as P acquired two distinctive caws—translated into English as “ark” and “wok”—by imitating the fish crows that often flew overhead (this was in Maryland.) Several months later, P’s sister RU began to use the call in her song as well, further harmonizing the family chorus.

QUOTH

the

CORVID

the

CORVID

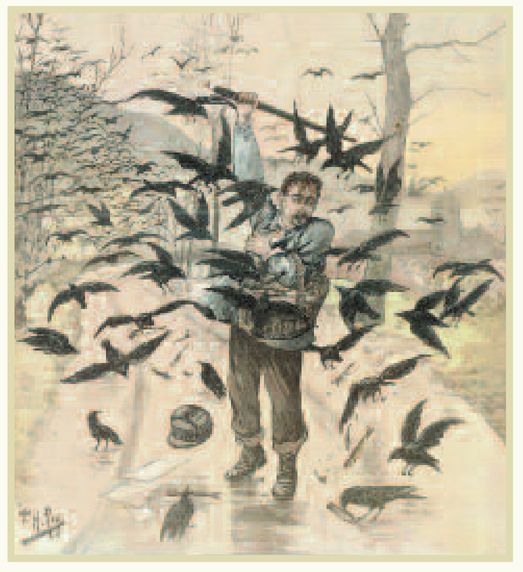

A French fish peddler is ambushed by a noisy mob of crows, 1899.

A French fish peddler is ambushed by a noisy mob of crows, 1899.GREEK PHILOSOPHER THEOPHRASTUS, CA. 371-286 BC

I

t is a sign of rain if the raven, who is accustomed to make many different sounds, repeats one of these twice quickly and makes a whirring sound and shakes his wings. So too if, during a rainy season, he utters many different sounds, or if he searches for lice perched on an olive-tree. And if, whether in fair or wet weather, he imitates, as it were, with his voice, falling drops, it is a sign of rain.

t is a sign of rain if the raven, who is accustomed to make many different sounds, repeats one of these twice quickly and makes a whirring sound and shakes his wings. So too if, during a rainy season, he utters many different sounds, or if he searches for lice perched on an olive-tree. And if, whether in fair or wet weather, he imitates, as it were, with his voice, falling drops, it is a sign of rain.

H. DOUGLAS-HOME, BIRDMAN, 1977

R

ooks were always said to be ominous birds. In the last century there was a rookery near the castle at Douglas, and when my great-grandfather was fairly young he got irritated by their cawing and ordered the keepers to get rid of them, about three hundred nests. An old crone bawled him out for banishing the rooks.“You wait, they’ll be back the day you die!” The time came when he was slipping away and suddenly, to his horror, all the rooks came cawing into the trees around Douglas Castle.“God Rooks!” he exclaimed and subsided into his pillows. “That means I’m going to die today.” And he did.

ooks were always said to be ominous birds. In the last century there was a rookery near the castle at Douglas, and when my great-grandfather was fairly young he got irritated by their cawing and ordered the keepers to get rid of them, about three hundred nests. An old crone bawled him out for banishing the rooks.“You wait, they’ll be back the day you die!” The time came when he was slipping away and suddenly, to his horror, all the rooks came cawing into the trees around Douglas Castle.“God Rooks!” he exclaimed and subsided into his pillows. “That means I’m going to die today.” And he did.

Other books

Bond Betrayed by Ryan, Chandra

Crossed by Lacey Silks

Too Close to the Sun by Sara Wheeler

Texas-Sized Temptation by Sara Orwig

Pure Joy by Danielle Steel

A Little Love by Amanda Prowse

Dirty Beautiful Rich Part Four by Eva Devon

Three Promises by Bishop O'Connell

Soul Love by Lynda Waterhouse

Not My Will and The Light in My Window by Francena H. Arnold