Cyclogeography (11 page)

Authors: Jon Day

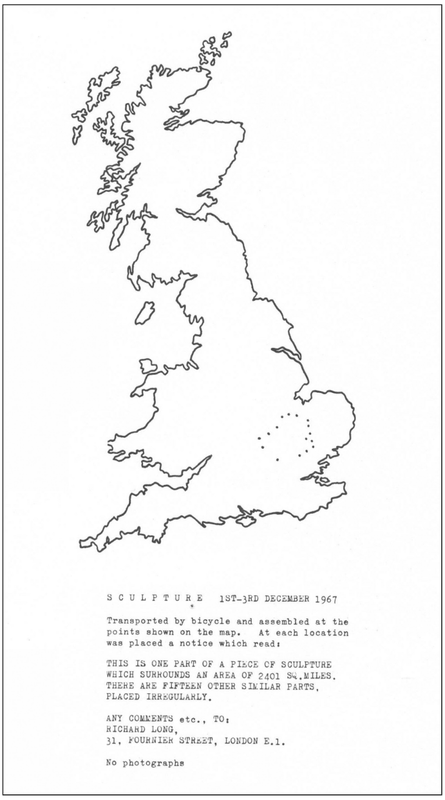

When I discovered Long’s map I saw it as a challenge. I wanted to ride the route myself, to recreate the event of Long’s journey, to see if I could experience what it might be like to turn a bicycle ride into a work of art. But I didn’t quite know what the route the map described should be. When he made his sculpture the road system provided Long with his basic structure. The rest was inspired by what he described in a letter to me as a process of ‘random attractiveness’. There was no forward planning. He was moved only by the environments he encountered to mark his arbitrary points on the map. ‘I did not draw it or plan it first,’

he wrote:

or even mark it afterwards, – only the ‘sculpture’ points. I remember (in particular) empty fen roads, Ely cathedral & also passing

by chance

! Henry Moore’s studio/village – Much Haddon? And the fire engines at the crash.

The Sculpture points were also ‘random’ but chosen for ease, practicality and to be fairly evenly spaced, one from another. They were always near or adjacent to the road.

Long’s map was only half the story.

‘The audacity of Long’s early work,’ writes the author Robert Macfarlane, ‘lay in freeing sculpture from the constraints of scale. He dispersed his art into the landscape, busting it not just out of the gallery, but out of almost all spatial limits.’ The mock-terse note on the signs he erected as part of

Cycling Sculpture, 1–3 December

is testament to this: ‘No Photographs’, a simple statement of fact. This was a sculpture it would be impossible to photograph, impossible to see, unless you went on your own journey around it. This was Long’s great artistic realisation. ‘I could make a piece of art which was 10 miles long,’ he recalled in 1986, ‘I could also make a sculpture which surrounded an area of 2,401 square miles […] by almost doing nothing, just walking and cycling.’ The action formed the map but the artwork itself existed nowhere, somewhere in-between the ride and its record.

Many of his works are secret, unacknowledged, hidden. ‘I like the idea,’ he once told an interviewer,

‘of making art almost from nothing or by doing almost nothing. It doesn’t take a lot to turn ordinary things into art. It is enough to use stones as stones, for what they are.’ Anonymity is key to much of what he does, but because of this subtlety his work re-enchants the world, making you read it in a new way. After exposure to Long’s work you never quite know if that stone by the side of the road was left deliberately or is there by random chance. In a sense it doesn’t really matter. ‘I love that,’ he has said, ‘I love the idea that people might see a work of mine in the landscape, and that they might recognise it as human mark but not necessarily as a work of art. Let alone a work made by me. So often people find a circle of stones and think it might be a Richard Long. Other people can make my work for me.’

I wanted to leave London and follow Long’s map, a map of empty space, a series of ghostly waypoints scattered across the landscape. It was October, the weather was warm and looked like it would hold for a last few days before the winter came. I thought I’d get a journey out of it – a structure emerging from the ride, connecting the dots. I wanted to leave the rutted runs of the courier-circuit behind. Long’s project was too tempting to ignore: fifteen points making no reference to cities, to pick-ups and drop-offs, or to the landscape itself. The gravitational sling of London throwing you out before drawing you back in. Emptiness and the road.

I wondered if there would be any connection between my discoveries as a courier and Long’s sense of the bicycle journey as art. I liked, too, the idea of a journey made not according to the dictates of controllers and clients, nor according to the tyranny of the

A–Z

, but within the looser confines of Long’s map. And so I decided to emulate Long, to recreate

Cycling Sculpture

, to go on a circuit that would take a few days to complete and wouldn’t end back where I began.

I overlaid the route over a map of Britain and plotted the rough course: out through Hertfordshire, through Aylesbury, Buckingham and Towcester. Then north through Cambridgeshire, bypassing Peterborough and Huntingdon, before heading north to Ely, marooned in its island in the fens, before turning south again for Cambridge, Newmarket and then down to Bishop’s Stortford. It would be a long ride, quite different from the day job, giving me time to lose myself on the road. I’d do nothing else.

Before I set off, however, I wanted to speak to Long about his journey, to find out what he had to say about the bicycle ride not just as experience, but as art. So I sought him out. We met in the Magdala pub in Hampstead, famous as the place where Ruth Ellis shot her lover David Blakely in 1955, subsequently becoming the last woman to be hanged in Britain. You can still make out the bullet holes in the wall outside – faint traces, like Long’s work, of historical events scored subtly into the surface of the world.

Though nearing seventy, Long is tall and lithe, with the enthusiastic, boyish air of a Scout Leader. He was wearing a nondescript anorak and sturdy walking boots. His eyebrows are the only unruly things about him, sprouting up over his forehead and giving his face a permanent expression of faint surprise.

Long said he couldn’t remember much of the route of this, his first Cycling Sculpture, or of the journey itself. He remembered riding through Tring, and recalled passing Ely Cathedral in the dark during the small hours of the second morning of his ride. He remembered sleeping for a few hours in a shed by the side of the road, lying on piles of mangelwurzels and being woken by hundreds of rats that had emerged from the woodwork to nibble on them. He said he had received a single enquiry about his signs, from a man on whose lawn he’d placed one part of his sculpture. He couldn’t remember what the man had asked him.

On the way back home through east London he remembered passing the smouldering aftermath of a car crash, with firemen cutting someone out of their car with acetone torches. ‘The smell was unbelievable,’ he recalled, ‘burning rubber, thick black smoke. I think there was blood on the road, and I just whizzed by on my bike.’

The idea of the piece, he told me, was to create a sculpture bigger than any other: to create a sculpture that could not be viewed all in one go, couldn’t be consumed from one single vantage point, that resisted the

tyranny of the gaze. The idea of the work was to be bigger than the reality. The piece was part of a body of work that played with scale. Long had once erected a sculpture on the top of Kilimanjaro, telling the papers that he’d created the world’s highest sculpture. ‘For some reason they didn’t consider it newsworthy,’ he told me. ‘Really it’s the shape itself that was important,’ he said of

Cycling Sculpture, 1–3 December

, ‘you could do the same ride anywhere, move the markers, place it over a map of London. The actual landscape I travelled over is unimportant.’

Long’s art is founded on the traces left by the body in motion, but in its making it is also about the enjoyment of the body, and this he associates with his own childhood pursuits and interests. The joy of bodily exertion I’d discovered as a courier he’d applied to the making of art. ‘Lots of people make art out of anguish,’ he says, ‘I make mine out of pleasure.’ As a boy he’d always been a walker and a cyclist. His parents met because they were both members of a rambling club, and at school he was the captain of the cross-country running club.

He’s often misread as a romantic artist, or as a political radical of some kind. I asked him if there was anything of the activist about his work – suggesting as it does ideas of right-to-roam and open access – but he told me he was an ‘art animal, not a political animal’. He does, however, draw a distinction between his work and that of the American land artists, who

use bulldozers and earthmovers to shape their environments to their will. His work isn’t interventionist in quite that way. ‘I’m not interested in imposing myself on the world,’ he said.

Stories do seem central to his practice: the story of his own body moving through space and time, the story of the marks he makes as he goes, but he resists over-investing in the idea of art as a form of narrative. ‘I don’t have any great grand theories of walking, or of making art into a journey,’ he told me later, ‘they just seemed like good ideas at the time.’ Though the backdrops to his journeys – mountains, forests and deserts – are often beautiful, they are largely irrelevant, or, if not irrelevant, a happy outcome of the pieces he makes. Instead he talks enthusiastically about technicalities and practicalities. Of the making of

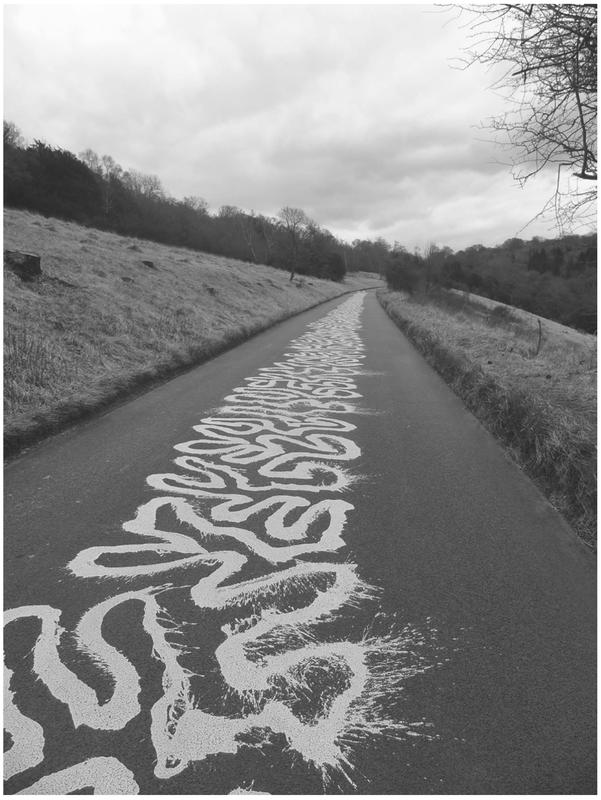

Road River,

a meandering line of paint he dripped onto the tarmac of Box Hill in Surrey, to be ridden over by the road cyclists during the 2012 London Olympics, he said, ‘we had to use biodegradable paint. And we had to do it overnight, and the paint would dry very quickly.’ He’s interested in what he has done rather than in why he has done it.

Outside the pub, as we were leaving, he examined my bicycle. ‘A track bike?’ he asked. ‘That’s a strange choice.’ He asked me who I thought would win the Tour. ‘Chris Froome’s looking good,’ I said.

‘He is,’ said Long. ‘Well, never meet your heroes,’ he said, as he smiled and stalked away back up the hill.

Richard Long,

Road River

(2012)

I left the next day, at first light. London fell away gradually and I never really knew when I’d moved beyond it. After a while the city gave way to suburbia, to the monolithic headquarters of medium-sized companies, to traffic depots and mysterious sidings by the motorway,

to increasing rural paranoia. There were signs on fences reading ‘Country Watch operates here’. The roads altered too, out here, roughing themselves up, clad in a firmer asphalt covering the better to resist the trials of winter.

The ride took me three days. I wanted to exhaust myself in the recreation. I didn’t stop to take notes, and I now remember the journey only as a litany of events, sequences stitched together by the rhythms of the bicycle. Like some of Long’s ‘text works’, in which he simply lists the actions he performed during one of his journeys, in the end I was left with just a sequence of names – towns I had glided through in the October sunshine, unnamed copses I camped in as night fell. I remember fragments, frozen scenes from a steady stream of images: Halloween decorations; hobby-farmers selling squashes by the side of the road. Honey at £4 a lb. Eggs £1.20 per half dozen. Hertfordshire, ‘County of Opportunity’, signs to a nearby Hare Krishna temple. A canal towpath by a fishing lake with a huge fibreglass dinosaur peering over the fence. A lake with signs announcing the presence of a malignant shrimp invader: ‘wash your tackle in the fresh water provided’. Dead badger roadkill, squirrel parchment, stoats, pigeons and tits, all squashed into the tarmac.

I moved down unmarked roads, roads that didn’t appear on any map, the products of the expansion of satellite towns with their branded mottos: ‘air to

breathe, space to think, room to grow.’ I placed my first post and sign on a telegraph pole outside Aylesbury, above a poster for the ‘Cirque Normandie: the spectacle magnifique’. After that I lost track of where I placed them: in fields, on embankments by the side of roads, in the middle of village greens. No one seemed to notice. No one stopped me.

At Silverstone, stinkpot mushrooms pushed through the boy-racer tempered tarmac. It was sunny, the mist had burnt off. Everything was geared toward the car round here: the racetrack itself was a monument to automobility. Cars rushed past.

I slept in a copse outside Northampton, listening to the cries of pheasants as the sun went down. Later they were replaced with the hoots of owls. I listened to the fizzing of a power line, hearing the surge in the grid as a million homes made tea before dying down to a gentle hum as people went to sleep. A gamekeeper had left a necklace of dead corvids – crows and jays – hanging from a fence in the clearing. A shooting platform sprouted from the trees overlooking a blue-barrel feeding station for the pecking pheasants. This was John Clare country, I slept near the asylum in which he was incarcerated for four years before he absconded and walked north to find his lost love.