Danny Allen Was Here (15 page)

Read Danny Allen Was Here Online

Authors: Phil Cummings

Danny stepped back and looked on, feeling useless. It was like watching a movie, a really good movie that kept you on the edge of your seat.

Vicki and Danny were watching so intently and Sam was hanging so precariously that not one of them noticed Adolf slink into his car and drive away.

Sam scrambled and kicked. He pulled and grappled determinedly. And, like all good heroes in movies, he regained his balance and stood once more. He made the crossing. Once at Vicki’s house he lifted his hands triumphantly above his head.

Vicki clapped.

Danny gave a cheer. ‘I’ll give it a try now, shall I?’ he called.

Sam looked to the bridge. He took hold and shook it. ‘No, no, you’d better not. We need to stop it from wobbling so much first. You’ll fall off if we don’t.’

Danny glanced at the ground. ‘Okay,’ he said. He was disappointed, but didn’t want to split his head open. They all climbed down.

As soon as the children had gathered together beneath the two pepper trees to make plans to steady the bridge, their mother called to them. ‘Come inside, children, please. Hurry up.’

They hurried inside, Vicki skipping, Danny jogging and Sam walking, all expecting cake or biscuits or . . . but their mother didn’t look at them. She was looking out of the back window.

Danny thought she must be coming down with a cold. She was sniffing and had a handkerchief in her hand. Danny’s dad was nowhere to be seen. Before their mother could say anything the tractor roared to life and the boys leapt to their feet. ‘Hey wait up, Mum!’ they cried. ‘Dad’s going on the tractor. We want to go with him.’

‘Me too!’ said Vicki.

‘No!’ said their mother firmly.

‘But where’s he going?’ asked Sam.

‘He’s going to finish fixing that fence by the creek and wants to do it alone, so sit down.’

She still didn’t turn around, but the children sat.

‘But he might need us,’ said Danny.

His mum’s shoulders lifted as she drew in a big strong breath. Then she said with a sigh, ‘Yes, he does need you, but not at the creek. He needs you here to pack things away.’

‘To pack what away?’ asked Danny.

‘Everything we have,’ said Danny’s mum. She took a long, deep breath. ‘We’re leaving the farm, children.’ She breathed again. ‘We’re moving away from Mundowie.’

Silence.

Danny’s dad returned after dark as the children were eating their dinner.

He walked into the kitchen. All heads turned to look at him. He took his hat off (the one with the oil stain that looked like a tiny map of Africa) and placed it on a chair.

Danny didn’t like the silence.

‘Did you fix the fence, Dad?’ he asked.

‘Yep, all done.’

‘So the sheep won’t try to fly,’ said Vicki with concern. ‘They won’t squish?’

Danny’s dad had no idea what she was talking about. ‘Fly?’ he said, puzzled. ‘No, the sheep won’t fly.’

‘Good,’ Vicki said.

Danny threw glances back and forth between his mum and dad. He was about to say something, but Sam beat him to it.

Luckily, Sam said what Danny was thinking. ‘So what are we going to do?’

Danny’s dad sat at the table and looked at each of the children in turn. Danny saw a turtle-like tiredness in his eyes.

‘Well, we’re moving to the city,’ he announced. ‘I was a carpenter once, so I guess I can be a carpenter again.’

‘The city!’ cried Sam. ‘Wicked!’

Danny felt his stomach turn upside down. ‘Couldn’t we just live here and not have the farm, like Mark Thompson’s dad?’

‘No, I’m sorry, Danny, there’s no work for me here.’

Danny tilted his head curiously. ‘Why did you fix the fence, Dad, if we’re not staying?’

Danny’s dad took him by the shoulders and gently squeezed. ‘I don’t want anyone coming onto the farm and saying I didn’t look after the place.’

Danny straightened himself. ‘No one would say that, Dad,’ he said, taking offence at the thought. ‘You’re a good farmer. It’s not your fault the sky didn’t rain at the right time.’

Danny’s dad managed a smile. ‘Well, when you put

it like that,’ he said, gently ruffling Danny’s hair, ‘I suppose not, Danny.’

Danny’s mum and dad embraced. Danny’s mum buried her face in his shoulder and dusty shirt.

Danny got up and went to his room; he never knew what to do when grown-ups cried.

In bed Danny and Sam lay awake.

‘I knew this was coming,’ said Sam quietly.

‘How did you know?’ asked Danny.

‘Come off it, Danny. Don’t you notice anything?’

‘Like what?’

‘The bank meetings, the papers all over the table, Dad’s extra job fixing the playground. He always said he needed a sheep dog, but he didn’t get one when Tippy died; he got a dog he knew would be okay in a city house.’

Danny suddenly had a rude awakening. Sam was right. Danny thought back. When they were painting the playground his dad had said something about trying to hang on. And when Billy came he

had

said something about not needing a sheep dog. There were other things as well, but Danny hadn’t noticed because he’d been too busy with the adventures of each day. There didn’t seem to be any need to think about tomorrow. It was always too far away.

Sam rolled over. ‘Anyway, the city will be brilliant, there’s heaps to do.’

‘There’s heaps to do here,’ said Danny.

‘Yeah, but not like the city.’

Danny put his hands behind his head and stared up at the ceiling.

‘No,’ he mumbled.

As tired as he was, Danny couldn’t sleep. He tossed and turned. When Sam started snoring he crawled out of bed and went diving into the darkness under his bed in search of his moneybox. When he found it he waddled off toward the kitchen. Billy jumped from the end of the bed and wandered with him, hoping for food.

Bright moonlight streamed through the kitchen window. Danny peered out. The world was silver. The brilliant moon, not quite full, sat like a huge pearl on a bed of black velvet surrounded by millions of tiny diamonds. Danny felt as though he was gazing through the window of a dream. The dark didn’t matter.

Danny sat at the table. The clock was ticking and the fridge humming. He opened the little cap at the bottom of his moneybox. Billy looked on, licking his lips. Danny emptied all the money out onto the tablecloth and counted – it was seventeen dollars and fifty-five cents. Danny piled all the notes and coins neatly and left the money next to the folder that said

BANK

on the spine.

He gazed dreamily out of the kitchen window

down to the shed. The rope bridge reached out to him from the deepest darkness beneath the shelter of the pepper trees and into the moonlight. He had to climb it, just once. He had no idea when they were actually leaving, but if they left the next day he would never get the chance to do it.

Danny Allen walked out into the night with Billy by his side. The yard was wonderful in moonlight. Everything was so still and so peaceful. There was nothing to be afraid of.

Danny walked down toward the shed, conscious of the sound of his own footsteps. Unfamiliar in the shadows, the old tractor was like a sleeping monster. Danny climbed the tree, slowly but surely. His boots flipped and flopped without socks. Beneath the tree the ground was decorated with puzzle-like pieces of moonlight shadow. Billy walked through them, sniffing, wondering where the chickens were.

Danny climbed to sit on the cubby house. Under the leaves it was very dark. He stood to grasp the rope bridge.

He held the side ropes. They were still loose. The bridge never looked very high, but once he was standing on it the ground seemed miles away.

Danny didn’t think about falling, or his head splitting apart like a dropped watermelon. He took a deep breath and stood tall, then took his first step

alone, out into darkness. Ahead, only two steps away, was the brilliance of the moonlight.

Like a moth, Danny headed for the light. The bridge swayed with each cautious step.

Before Danny knew it, he was halfway across. He smiled to himself. This wasn’t hard. He wasn’t going to get hurt. He wouldn’t fall now. His head wouldn’t crack apart and spill his brains on the dust by the tractor shed. There was nothing to be afraid of, or worried about.

Danny stopped in the full glow of the moonlight. He stood in the middle of the rope bridge. He looked across the roof of the house to the Mundowie Institute Hall. The moonlight made the white marble soldier statue glow like the ghost gums down at the creek.

Danny sniffed the air like Billy. He looked in all directions at everything he could see. The moonlight on the roof and the white chimney; the silhouette of the rooftops across the road; Mark Thompson’s rooftop.

Even the white gravel road that cut through the town was glowing. It didn’t look hard and full of stones. It looked like a fluffy blanket. Danny didn’t want to get off the bridge. He lay down on his back as if it were a hammock. He kept a firm grip on the ropes and stared up at the stars.

This was a magical world.

This was Danny Allen’s place.

Leaving

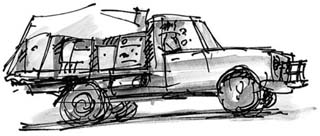

The day Danny Allen left Mundowie his house was a whirlwind of activity. Mark Thompson’s dad had offered his truck to help with the move. He was carting furniture out the front door with Danny’s dad.

‘Watch your step, don’t fall backwards.’

‘Hang on, my fingers are trapped. A little to the left, hold it! Hold it!’

In the yard Billy was playing his scatter-the-chickens game.

Yap! Yap!

Pertakeerk, cluck, cluck, cluck

.

Danny’s mum was directing everyone. Clumps and strands of her hastily clipped hair were hanging untidily. She stood in the kitchen doorway pointing and barking orders.

‘Danny, pick up that last box in the bedroom and help Sam take it out to the truck. Vicki, stop dancing and help, please.’

‘In a minute,’ Vicki replied as she readied herself for a twirl across the open kitchen floor. She loved the empty house. The bare floorboards and empty rooms provided her with stage after stage upon which to spin and spring about.

Danny didn’t like the emptiness. ‘Stop fooling around,’ he grumbled, deliberately walking into Vicki’s twirling path. ‘You have to help.’

Vicki stopped and frowned at him. ‘Get out of the way. I will in a minute.’

Before Danny could argue, Sam called to him from the passageway. ‘Danny, hurry up!’

Vicki put her hands to her hips, tapped her foot impatiently, waited for Danny to get out of her way, and then went on twirling.

At the front of the house the old Thompson truck was loaded with cupboards, beds, the fridge, boxes and suitcases. At the very top of the furniture mountain

sat the old kennel that Billy had inherited from Tippy.

Not everything would fit on the truck. Some of the furniture had been stored in the Wallaces’ shed. Aunty Jean thought it was a good idea. ‘It means you’ll have to come back to visit,’ she said with a laugh.

When the house was completely empty Danny didn’t like wandering through it. The echo was weird and Vicki’s non-stop dancing annoyed him.

Once the chickens had been rounded up and caged, the deserted yard was eerily quiet. And looking down toward the tractor shed to see the rope bridge hanging alone made Danny’s stomach churn.

Danny’s mum said, ‘I hope we’ve got everything. I’d hate to leave anything behind.’

‘Oh no!’ Danny suddenly cried. ‘I

have

forgotten something. Don’t go yet. Don’t go.’

With that he took off across the road. Billy took off after him.

Yap! Yap!

He gave up the chase when he realised he was going to be left behind.

Everyone was puzzled, even Billy, as they watched Danny run off.

‘He’s not running away again, is he?’ said Sam. ‘I can’t wait to get to the city and I want to get there before it’s dark.’

Vicki didn’t like the sound of the city in the dark.

She swallowed and said, ‘We

will

get there before it’s dark, won’t we, Mum?’

‘Not at this rate.’

Sam nudged Vicki. ‘It doesn’t matter,’ he said. ‘The city is brilliant at night. All the lights look like the stars have fallen from the sky.’

Vicki looked up at Sam. ‘Will it be good in the city?’

‘You’ve been there,’ said Sam. ‘Remember all the shops we went to?’

‘Yeah,’ Vicki nodded.

‘We’ll be able to go every day if we want.’

Vicki liked the shops. She had bought her favourite necklace there the last time they went. But then she looked at Sam, tilting her head quizzically to one side, and said, ‘But where will we get tadpoles?’

Sam shook his head. ‘I give up. You’re hopeless.’

Vicki didn’t understand his terse reaction. She thought it was a fair question.

Danny ran across the road and under his lookout tree, past the Mundowie Institute Hall without a salute to the white soldier statue standing guard and off toward the creek. As he flew past the playground he heard a voice calling to him. ‘Danny! Danny Allen. Hey there!’

It was Aunty Jean Wallace. Danny didn’t stop.

He waved to her as he passed. ‘I’ll be back in a minute, Aunty Jean.’

Down toward the creek he ran, racing through shadows, leaping dead logs, stomping with determined footsteps on the crackle-dry grass.

He flew away, leaping down a slope, arms waving like the wild flapping wings of the noisy cockatoos shrieking from the gum trees overhead.

Aunty Jean leant on her fence and smiled as she watched Danny race over a crest, then dip and disappear below a horizon of thick yellow weeds.

At the creek, Danny ran along its banks. As he passed each familiar landmark, he remembered different adventures. First there was the sheep track that they had slid down to go sand-dune surfing, then the drums that they made into a grandstand before they were the sad site of Tippy’s death. Above the drums the lonely tyre hung over the dry creek bed and finally he passed the slope down which the tractor tube flew on muddy days. There were so many things to remember.

Danny didn’t stop to reminisce; there wasn’t time. He kept running until he reached the spot. His secret place.

Puffing hard he dropped to his knees. In he scrambled without fear. After all, the leaping vampire snake was dead now; Tippy had seen to that.

His eyes blinked furiously and fingers of dusty

sunlight reached into the darkness. Danny knelt and looked down at his treasures. The tadpole-hunting tin, full of little bits and pieces, sat next to the ram’s skull. Danny scooped everything up and took one last look at his secret place, goosebumps pricking across his shoulders at the memory of his snake encounter. With the tin in his hand and the skull under his arm he scrambled from the half-darkness back into the light. Careful not to drop the tin or the skull he headed back to Mundowie.

Danny jogged up the slope and emerged from the shadows of the creek, and he spied Aunty Jean still at the fence.

Danny hurried over to her.

‘Sorry, Aunty Jean,’ he puffed. ‘I had to get my things.’

Aunty Jean looked at the skull and the tin with a wry smile. She said, ‘I’ve got something else for you. Can you carry one more thing?’

‘What is it?’ asked Danny.

She offered him a parcel wrapped in red crinkled wrapping paper which was obviously second-hand. ‘This is for you,’ she said, tucking it under his arm.

Danny looked at the present. ‘Thanks, Aunty Jean. What is it?’

‘It’s a surprise,’ she said with a wink. ‘But don’t open it until later. Perhaps when you’re driving along.’

Aunty Jean reached out and cuddled Danny, sheep skull and all, and gave him a peck on the cheek. ‘Good luck, Danny Allen.’ Her voice was crackly like a radio not quite tuned in to the station. ‘We’ll see you when you come back to visit. And don’t worry; we’ll take good care of your furniture.’

‘And Mundowie,’ added Danny.

Aunty Jean ruffled Danny’s hair. ‘Oh yes,’ she chuckled. ‘Of course.’

‘Thank you, Aunty Jean,’ Danny said.

Danny turned away and set off to say goodbye to his empty home.

When Danny arrived back everyone was standing in front of the truck. His mum looked at his load, shook her head and said, ‘So have you got everything you need now, Danny?’

Danny looked at his mum and dad, at Sam and Vicki, who had Billy in her arms, at his tin, the skull and the red box being crushed under his arm. After a thoughtful pause he nodded firmly. ‘Yep, I have . . . I think.’

Sam and Vicki were going in the car with Billy. Danny wasn’t going in the car. He’d won the right, after a hotly contested tournament of paper, scissors, rock, for the first ride in the truck.

He sat between his dad and Mr Thompson.

Danny looked out the window when he heard Mark Thompson calling from across the road.

‘Hey boys! Yo!’

Danny leant forward to peer past his dad. Mark was at the side of the Mundowie Institute Hall.

The Thompsons were staying in Mundowie for the time being.

‘Hey Danny!’ Mark yelled. ‘Remember the ten.’

Danny beamed. He leant across his dad and stuck his head out the window. ‘Yeah!’

‘Watch this,’ Mark called. ‘Watch.’

Danny gazed out of the open window with his eyes peeled on Mark.

Mark Thompson spun round, took his footy from under his arm and kicked it at the Mundowie Hall. Danny watched, expecting to see it sail over the top, but it didn’t. In fact, it didn’t even go close. It hit the gutter and bounced back.

Mark jumped and caught the ball in his hands. He tucked it under his arm. ‘One day I’ll get it over,’ he called.

Danny shook his head. ‘What do you mean?’

‘I’ve never done it, Danny Allen.’ He laughed. ‘Never!’

Danny was shocked. ‘What?’

With a crunch of gears, the truck slowly drew away from the house. Danny looked back and watched Mark try again and again to kick the ball over the Mundowie Hall. He couldn’t even get it onto the roof. Danny watched Mark until he was lost in the dust.

Then Danny sat silent in the truck and looked to his dad. He wasn’t wearing his farming hat, the one with the oil stain that looked like a tiny map of Africa.

Danny’s dad looked down at the big tin with the wire handle that was sitting in Danny’s lap.

‘Why are you holding onto that, Danny?’ he asked.

Danny lifted the tin. ‘This is the tin we used for tadpole hunting.’

‘Tadpole hunting?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Where? Not at the dam?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Your mum didn’t tell me about that. And I thought I had made it perfectly clear that you weren’t . . .’ He stopped in mid sentence and sighed. ‘Ah, what does it matter now? And anyway, I bet I don’t know half the things you kids get up to.’

Danny smiled at his dad and thought about what he’d said. Then Danny thought back to his dad’s bank visits, the bad seasons on the farm and the evenings his dad sat poring over the financial folders obviously in desperate trouble, but he didn’t let on. And Danny thought,

Well, I don’t know half the things you get up to either, Dad

.

Danny’s dad leant over and peered into the tin. ‘What have you got in there now? I know there aren’t any tadpoles.’

Danny took things out one by one, starting with Tippy’s collar. Danny held the collar and shook it gently to make it jingle.

Then he held up his baked head that his mum had cooked for him. Danny didn’t need to explain that one, his dad knew all about it. He had varnished it to keep it preserved.