Dawn of Fear (5 page)

Authors: Susan Cooper

Â

“I don't see why we couldn't get through here,” Peter said.

“But it's barbed wire. You'd get scratched to bits.”

“And then you'd get lockjaw,” Geoffrey said with relish. “That's what happens when you get rust in a scratch. Your jaw goes all stiff, and you can't open your mouth, and you can't eat or drink, so you just starve to death.”

Peter ignored him. “Look, Derry,” he said. “If I push down the bottom bit of wire, like this, and hold up the top three, then you can squeeze in between them and get through. I won't let it stick in you, honest. Go on, try.”

“He's scared,” Geoffrey said.

“I am not,” said Derek, who was. He looked nervously over his shoulder at the allotments, but saw no change in the few figures bent devotedly over spade or fork; he looked up at the cabbage field and in front of him at the length of the Ditch, but could see nobody there. So he squeezed himself headfirst through the gap that Peter was holding open, caught only the edge of one shoe on the barbed wire, and tumbled down into the long grass on the other side. Then he held the wire in turn, and Peter came after him.

“You coming, Geoff?”

“I'll keep watch,” Geoffrey said.

Peter was already in the Ditch, trampling his way through nettles and grass. He clambered down to its lowest point, facing a steep embankment over which a few brambles reached feeble arms in escape from the back field thicket held back by the tall mesh fence. He ducked down, so that they could see only a glimpse of his fair head among the leaves and the mounds of clay, and then bounced up again, grinning with delight.

“Hey, this is smashing. Come and see. We've got to build the camp here.”

As Derek slithered down, half the world disappeared. The weed-feathered sides of the Ditch cut him off from Geoffrey, the cabbages, the surrounding fences and houses; and there was left only the tall side fence of the back field, with that gigantic sinister blackberry bush that seemed from here to be trying to push it down.

There was a glimpse of the similar fence that crossed the Ditch between the Robinsons' and the Twyfords' gardens, cutting off their own usual road-linked world; and nothing else but the sky. He stared happily about him at the orange-red earth and the lush grass and the rank clumps of weed.

Peter punched his arm lightly. “Like it?”

“It's perfect. Nobody would ever find it here. We could build a really good one and keep all sorts of things.”

“The way this hump here goes, look, we could just hollow out a bit of the back wall and put a roof across from it to the hump, and it would be like a room. Like our Morrison, almost.”

“Like the way the sandbags are around the guns up the road.”

“We could even get some sandbags.”

“Um.”

They pondered this for a moment. Somehow sandbags would not be right for their own camp. It was a timeless fortification, theirs; it grew in their minds out of a vague mixture of Iron Age earthworks and Saxon forts. They had known about such things for as long as they could remember, and not from books or school. The leavings of the ancient peoples were all around them in the valley of the Thames and the Chiltern Hills. Regularly they saw them, passed them, walked over them: the once-besieged fortresses, ten centuries old, which lay gentle now beneath soft-sloping grassy mounds.

“Not sandbags,” Derek said.

“No. But we could put a roof. The boxes would be good for that.”

“Have to do the digging first. Let's get the spade from the old camp.”

“Hey!” A plaintive yell came faintly down from the other side of the fence. Derek started, feeling guilty. He had completely forgotten about Geoffrey, keeping watch.

“That Geoff,” said Peter.

“Careful. He might have seen someone.”

They wriggled along the bottom of the Ditch, around the big clay hummock, and peered carefully up through the grass.

Geoffrey called, “You think you're so good at stalking. I can see you plain as anything. Lucky for you I'm not Mr. Everett.”

Peter stood up. “You've never seen Mr. Everett.”

“Nor have you. Come on, you've been down there for ages.”

Derek heaved himself up, picking last year's burrs off his sweater. “Come and look, Geoff. It's just the right place for the camp.”

“It's a moldy place,” Geoffrey said peevishly. “How can we come and go through that stupid barbed-wire fence? And I'm fed up with standing here keeping lookout. There isn't even anywhere for me to hide if anyone comes.”

“Nobody asked you to keep lookout,” Peter said coolly.

Then he relented and gave Geoff his sudden crooked grin. “Come on, hold the wire for me. We have to go and get the spade and everything from the old camp and bring them here to start digging. It really is a super place; wait till you see. There's loads of space to make storage holes. We can make a special hidden one to take birds' eggs.”

This was a deliberate peace offering; neither he nor Derek approved of collecting birds' eggs, regarding it as a particularly shameful kind of robbery. But Geoffrey, firmly explaining that he did no harm by taking only one egg from each nest, did collect them, and messily blow them, and keep them labeled in boxes in his room. When they had first thought of building the camp in their usual section of the Ditch, he had greeted the thought of it delightedly as a way station for newly taken eggs.

“So long as you don't touch our robin,” Derek said. A robin had nested two years running in a bush in the Brands' front garden; this was the first year they had let Geoff see the tiny pale blue eggs.

“I got a robin egg ages ago,” Geoffrey said loftily. But he was mollified. “Well, let me come through and see, then, if it's so marvelous.”

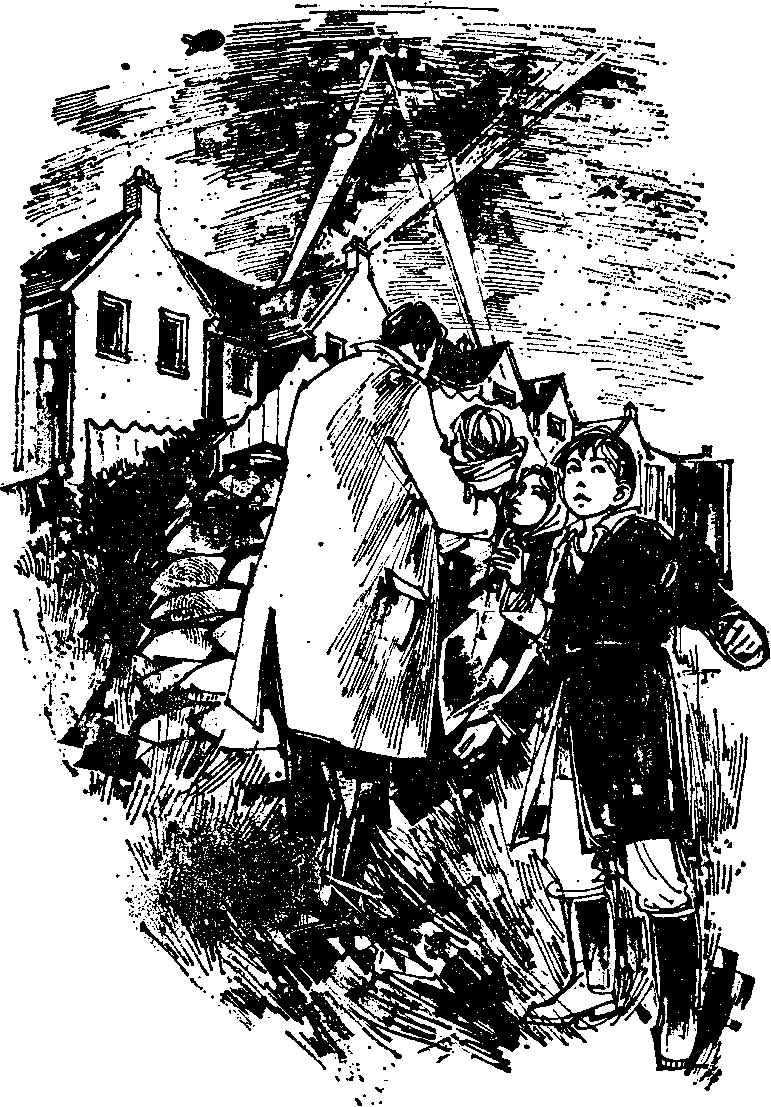

“Come and get our things first,” Peter said. He scrambled through the fence, casually ripping out a thread from his sleeve as it caught on the sharp hooked wire. “Why'n't you stay here, Derry, and keep an eye on it? We shan't be a minute. If we see your mum, I'll tell her we're just playing in the back field.”

“All right. Better tell her I'll be in soon. And mind you get my blowpipe and darts.”

He called after them, “Be careful with the darts. There's seven of them.”

From the stile, Geoffrey called over his shoulder, “They don't

work.

”

“We'll be careful,” Peter said.

Â

D

EREK CLAMBERED

down again into the ditch as they disappeared toward his back garden. A lone cabbage white butterfly flittered around his head, lighted briefly on a patch of bare clay, and meandered off again. He swiped at it absently, out of habit. Down at the bottom, he pulled a few clumps of weeds from the area that would be the floor of the camp, and stamped the ground down as flat as he could make it. Really, it would be a wonderful secret place. A real camp, this time.

He heard the sound of engines, crouched, looked up. The three Spitfires were coming back; farther away this time and more strung out. He thought: “I'm going to be a pilot one day. Or no, what I really want is to be a sailor, in a destroyer, like Commander Hansen down the road. Or perhaps I'll be a soldier, like Daddy was in the last war. With a gun.”

He thought about the gun. His father was a sergeant now in the local Home Guard; his newly acquired steel helmet, which he called a tin hat, hung in the hall on the hatstand, and the heavy service rifle stood on its butt in

the umbrella stand beneath it. The strictest rule in the house was that nobody should ever, on any account, touch John Brand's gun. Derek had touched it only once, on the day it first appeared, when his father had ceremonially put the tin hat on his head and the rifle in his hands. They had both weighed several tons. The helmet had been so heavy that Derek's chin had bent down to his chest for the second that John Brand had let the padded metal rest on his head; and the rifle so heavy that even with both hands and all his strength he had been able to lift it for an instant only an inch or two from the floor. And that had been that, and he had never touched the gun again.

The sun was warm. A large sleepy bumblebee wandered past his head. He forgot about the gun.

Then Peter and Geoffrey leaped down into the Ditch, whooping, Geoff carrying the spade and Peter carefully cradling the blowpipe and darts without one dart tip so much as bruised; and they set to digging out the first outline of their camp. They dug for a long while, taking turns with the rusty spade head, and by the time they had to stop for dinner, at Mrs. Brand's distant call from the back garden, the camp was well enough begun to be fitted with its roof.

Â

T

HE SKY

was clear all day, and still only a few chunky clouds had drifted across it by the time they went to bed. Before his mother pulled the blackout curtains carefully

over the windows in the chilly, darkening room, Derek could see the moon sailing tranquilly in and out of the clouds: gradually drifting sideways, moving in an endless flowing motion, and yet hanging always still. Then the shiny black cotton of the curtain blotted everything out, and it was dark.

“There won't be a raid tonight, will there, Mum?”

“Well, darling,” she said gently, “I hope there won't.”

“There's lots of cloud to cover the moon.”

“That's right. Let's hope they stay at home.”

“Be awful if they bombed our camp,” he said sleepily. “It's smashing. We're going to put a roof on it and camouflage it with grass.”

“Remember you promised me there wouldn't be any tunneling,” Mrs. Brand said. “That's dangerous.”

Derek yawned. “Just walls. And a sort of dent.” He had been so full of the thought of the camp that he had had to talk about it; but he had still kept it secretâhe hadn't said where it was.

“Good night, Mum.”

She kissed him. “Don't forget your prayers. Good night, my love.”

Sleepily he murmured the Lord's Prayer to himself and added the usual bit about blessing Daddy and Mum and Hughie.

Hugh coughed, across the room in his cot. There was a muffled sound through the wall, like a shifting chair, from the Robinsons' house next door. Derek snuggled

down under his quilt and felt earth still gritty under one of his fingernails.

Please God look after the camp,

he added. It sounded a bit odd, somehow, but he didn't think there was anything wrong about it.

Hugh coughed again, twice; stirred, moaned, turned over. “Good night, Derry.”

“Good night. Sleep well.”

“'N you.”

And please God don't let there be a raid tonight.

Â

B

UT IT WAS

the sirens that woke him. They were all going at once: two of them somewhere farther off, well started on their long-drawn-out, eerie rising and falling note; and then breaking into it suddenly, loud and harsh, their own local siren in the village, curving up out of nowhere in that first throat-catching whine that was the most chilling sound of any except the very last, the long, long, long dying-down wail that was the worst of all. But before the last wail came, they were all on their way out to the air-raid shelter, Derek with boots and two sweaters over his pajamas, and a coat over those; Hugh lying in a bundle of blankets in his father's arms. The night was very cold, and the moon had gone. The guns were already thumping somewhere close by, and planes were rumbling high overhead. As they hurried across the lawn, there was the night-breaking crash of a bomb, and the earth shook.

“Big ones,” John Brand said.

Mrs. Brand went quickly down the earthen steps behind the sandbag wall at the shelter's entrance, and he handed Hugh to her and turned to lift Derek down. The noise grew; planes were flying closer, lower, and the world exploded as the guns went into action at the end of the road. “Thunk ... thunk ... thuunk-thunk...”

Derek gazed upward, openmouthed, as light streaked across the sky and great sudden stars burst; the long white arms of the searchlights were groping to and fro in the black sky from those unknown places across the railway where they always sprang up at night, and one of them seemed to have gone mad. It was darting and weaving like a clumsy giant, and he saw the silhouette of a plane in its white light, a plane flying low, and he thought he could even see the crosses on its wings as another engine screamed and a Spitfireâhe could see the pointed noseâcame diving toward it through the beam.

“Derek!” John Brand yelled.

The sky flashed, and somewhere another of the great bombs burst. Derek went to his father, but his head was still back as he moved, the searchlight hypnotically holding his eyes. That plane was out of the light; you could hear it diving, shrieking; it was coming nearer, nearerâ

“Get down,” John Brand shouted furiously, and grabbed him and pushed him so roughly inside the shelter door that Derek lurched and fell over his mother's knees where she sat on one of the bunks. His father

ducked down after him, and the plane roared as it dived over the road, and there was a rapid, horrible clatter sweeping across the world with it at the peak of the noise. The guns everywhere were hammering the sky in an uneven thunder, and close together there were several great blasting crashes as more bombs fell.