Dawn of Fear (9 page)

Authors: Susan Cooper

“Sod off,” Tom said.

He stood there casually with one hand in his pocket, towering over them all. The Wiggs boy and his friends paused resentfully for a moment, and then turned and ran; ran until they were halfway down their road in the safety of their own territory, where they turned to run backward, yelling inaudible insults as they went.

Geoffrey laughed. “That scared them.”

“That Wiggs kid is just like his brother,” Tom said, frowning after them, his face unreadable. Then he swung around. “Come on, then.”

They made their way through Derek's garden, and as they reached the back door, John Brand came out in his slippers with some rubbish for the trash can. “Well,” he said. “Hallo, Tom. How are you? That's quite a procession you have there.”

“Can we show Tom something in the back field, Dad?”

“Provided he throws you all over the fence,” Mr. Brand said. “That might save it wobbling so much.” He grinned at Tom. “I hear you're joining the Merchant Navy; is that right?”

“That's right. Quite soon now. My dad was a sailor. It runs in the family.”

“I know he was,” Mr. Brand said. “And a good one. Well, we shall all be thinking of you, Tom. And there are

some of us old men who would give quite a bit to be with you.”

“There's just as much to be done here,” Tom said. “And it's just as dangerous.”

He sounded somber and adult; the boys shuffled, fidgeting to get away. John Brand looked at them absently for a moment, as if they were not there. “Well, the very best of luck to you, Tom,” he said, and they shook hands, and because of the uncomfortable gravity it was a release for Derek and Peter and Geoffrey to dance about Tom like sheepdog puppies, chivvying him down past the apple trees to the end of the garden. Derek said, as they crossed the back field, “We planted a bit of a blackberry bush at the entrance, like you said.”

“It doesn't look too good, though. The rain might have helped it.”

“We didn't half get scratched planting it. Look at that one.” Peter pushed up one sleeve and waved an arm with a long dark scratch from elbow to wrist. “My mum made me change my shirt when I came inâthere was blood all over the sleeve. She was wild.”

“Well,” Tom Hicks said gravely, “that shows your bramble's as good as barbed wire. It ought to keep any invaders out.”

But he was wrong.

They saw nothing until they had crossed the stile onto the allotment field and then made the U-turn back, around the end of the tall wire-mesh fence and through

the barbed wire, into the hummocks of the end of the Ditch. That was one of the good things about the camp, that you couldn't see it until you were almost on top of it. Derek was behind Peter and Geoff. Though he knew there was no need, he had paused solicitously to push down the top strand of barbed wire as Tom cocked his long leg over it. Grinning a little in anticipation, he watched them as he felt the straight part of the wire carve its rust-grained imprint into the palm of his hand. They bounded up onto the grassy hummock that ended the Ditch, from the top of which you looked down for the first time into the camp; and then for a long moment the world froze, and Derek pressed the wire harder into his handâeven though Tom was clear over it and standing at his sideâas he saw Peter and Geoffrey stop up there as if they had run into a wall, stop stock-still gazing downward, and saw the change that came over their faces.

He was looking at Peter, and he never forgot what he saw on Peter's face. The cheerful eagerness died as if a light had been switched off, and for a second there was no expression at all, an utter emptiness, until the mouth twisted into any number of emotions and all of them black. It was like small Hugh's face after the moment between his falling down somewhere and feeling the pain that said he had hurt himself, when he opened his mouth in a wide downward arc and brought out first a choking silence and then a wild, unhappy yell. But Peter did not yell. He turned back to them and said gruffly, “Look,” and

Geoffrey turned, too, and Derek saw the same stricken look on his face.

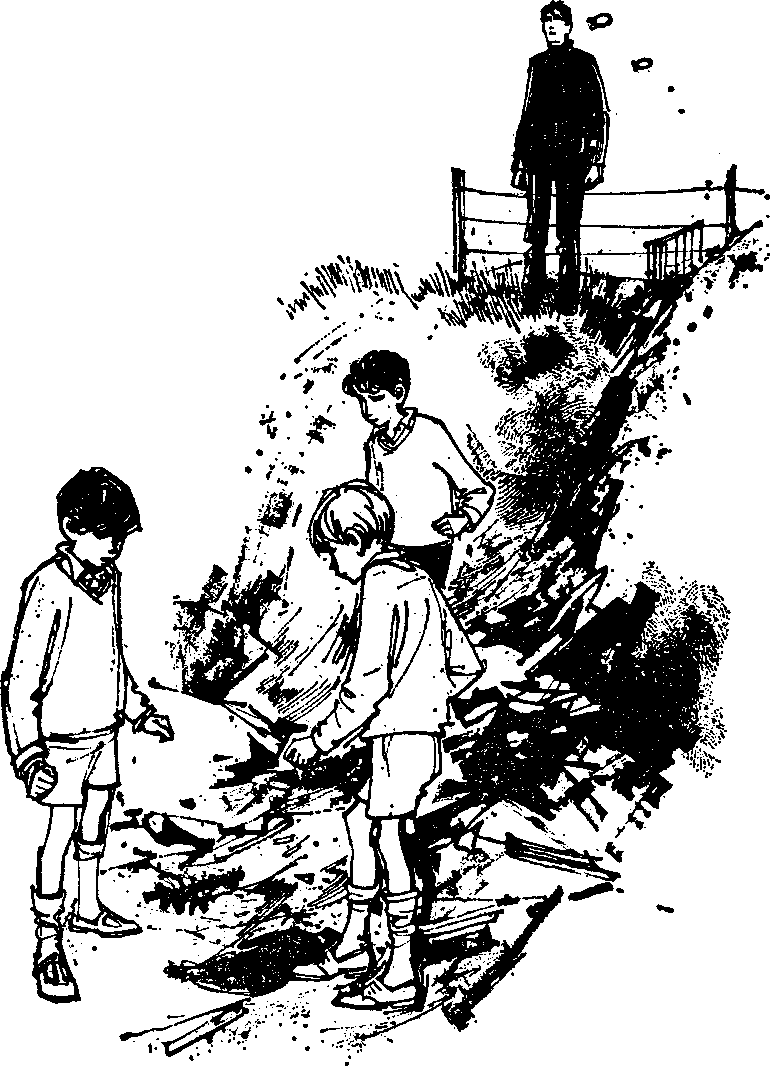

He moved up with Tom and looked.

Their camp was no longer there. It had been wrecked with such savage thoroughness that it was difficult even to make out the outlines of the walls they had labored to build up. The hillock on which they stood, and which they had carved painstakingly into a sheer straight wall, slanted down now into a rough, lumpy slope. The far wall of the camp, with its battlements, was completely gone: flattened into a muddy mess of clay. The side wall of the Ditch, which they had carefully hollowed into the secret cupboard and wall of the keep, was pitted and gashed with what looked like the blows of a spade. The cupboard was gone, too, and so was the roof, and instead the whole of the bottom of the Ditch, which had been the floor of the camp and was now a muddy, trampled bog, was scattered with torn-up fragments of newspaper and splintered pieces of wood.

None of them said a word. They stood and looked.

The three-armed bramble that they had planted at the camp entrance lay feebly in the muddy chaos, torn into three pieces. Between the crushed branches there were the crumpled remnants of a cardboard box, and here and there broken pieces of eggshell. Scattered over these were other relics that Derek did not even recognize at first. Only when he stepped silently down, the first of all of them, and picked up an odd-looking giant splinter, did

he see that his blowpipe and all its lovingly carved darts had been broken into very small pieces and dropped like confetti on top of the rest.

There was no sign anywhere of Peter's gun.

The thing that Derek noticed last of all was a thing that seemed to have no meaning: a small black heap that he took to be a wet crumpled rag, lying neatly in the very center of all the mess. His eyes and mind flickered on to it, and he wondered emptily where it had come from, and then he looked away again to a small blue-flecked fragment, pathetically delicate against the trampled orange mud, that he knew was a piece of Geoffrey's blackbird's egg. He stared down at it, not daring to look at any of the others. Peter stepped down beside him, slithering a little, and put one foot out gingerly to prod the crumpled black rag; Derek watched him, still numb.

Peter said, “It's the cat.”

“The what?” Derek gazed blankly, uncomprehending; and as the toe of Peter's shoe gently stirred the heap, he saw first the frayed end of a dirty piece of rope, and then something that could have been the tip of a very small black nose. “Oh no,” he said. “Oh, Pete, it can't be.”

Geoffrey slipped down beside them. “Yes it is,” he said.

“Is it dead?”

“Course it is.”

“P'r'aps it's just hurt,” Derek said, without hope. “It could be just unconscious. Couldn't it?”

Peter squatted down and put one hand gently on the small black heap. “Feel,” he said.

Derek swallowed, and bent down and touched it, and felt the stiff curve of a small knobby backbone and wet fur that was very cold. He drew his hand back quickly and said, without any thought of shame, “I feel sick.”

“Poor little cat,” Peter said, and put one finger under a small dead paw.

“Who did it?”

They had almost forgotten Tom, and they started at the depth of his voice; he was standing above them on the hillock, the only one of them who had not moved since the first sight of the ruined camp. He looked very tall there above them, and squinting up at the sky behind him, they could not see the expression on his face. From where Derek stood, he could see next to Tom's head the floating outline of the nearest barrage balloon that hung on guard in the sky; he saw the two shapes next to one another against the curious brightness of the gray unbroken clouds, and together they looked funny, but it did not occur to him to laugh.

“Those kids,” Peter said.

“The kids from the White Road,” said Geoffrey. “It must have been.”

Derek looked up at Tom and the barrage balloon, and he said, describing the memory as it came into his head, “We were coming out of the Ditch the other day, and we

saw David Wiggs and his gang with a cat, a little black cat. They were holding it up by a rope and strangling it and poking it with sticks, and we chucked stones at them and the cat got away. And they were wild.”

Geoffrey said, “And we saw them this morning with you, just now, remember?”

Just now,

Derek thought; it seemed a hundred years away. He said slowly, “They were saying something about the catâbefore you scared them offâand they were laughing.”

“They were shouting at us on the way up, too,” Peter said. “David Wiggs's brother was there with them then.”

“Ah,” Tom said softly. He came down the muddy slope into the camp, or what had been the camp, digging in his heels to avoid sliding, and he looked down at the cat. He said, “Someone must have drowned it.”

“Oh no,” Derek said quickly; he felt his throat jump at him again, and swallowed hard. “Wasn'tâcouldn't it just have got all wet in the rain?”

“Not that wet,” Tom said. Then he stiffened and turned his head quickly. “What's that?”

They heard faint voices and laughter, and scrambled up in time to see several figures running and leaping away toward Everett Avenue out of the front section of the Ditch, on the other side of the high impenetrable fence that ran parallel to the backs of the Everett Avenue gardens and cut the Ditch into two halves. The figures

ran to a taller figure waiting for them at the end of the White Road, and waved mockingly back behind them, and disappeared.

“That's Johnny Wiggs up there,” Tom said. He thrust both hands hard into his pockets and scowled. “That settles it.”

“It was them, then,” Peter said.

Geoffrey said bleakly, “I suppose they wanted to see how we looked when we found it all.” He bent down and picked up the tiny curved piece of the broken blackbird's egg, and the splintered handle of one of Derek's darts, and looked across at the blank churned earth where the secret cupboard had been. Then his head jerked up. “Pete. Your gun. Where's your gun?”

Peter shrugged. “It's not here, is it? One of them must have taken it.”

Geoffrey got up. “Well, you never know. They might have chucked it away.” He began roving around the edges of the Ditch, peering into the grass.

“Beasts!” Derek burst out. “The mean dirty beasts!” He looked up at Tom. “It was such a good camp, it really was. We had it all finished up. And now we haven't even got a chance to use it once. We had some of Geoff's birds' eggs in the secret cupboard, and a blowpipe and darts I made, and Pete's six-shooter gun with the carved handle, and we left them here, and they justâ” His voice wavered and disappeared, and he pointed miserably down at the litter on the mud.

“Well, they aren't going to get away with it,” Tom said. “And we'll rebuild your camp and make it even better than it was.”

“There's no point,” Peter said drearily. “They'd only come sneaking in and bash it down again.” He looked out down the Ditch toward the White Road, empty now except for two briskly walking housewives with shopping bags. “But if that David Wiggs has got my gun, he's jolly well going to give it back.”

“He will,” Tom said. “And they won't come near your camp again, either. We'll show them.”

“I don't see what we can do,” Derek said. “We can't even fight them, not all at onceâthere's too many of them. Three against seven just isn't any good.”

“Four against seven,” Tom said.

There was a silence, and they stared at him.

Peter said, “But you aren'tâthey didn'tâI mean, it's us they were getting at. You don't have to get into a fight because of us.”

“That wouldn't be fair,” Derek said. He added hastily, “Fair on you, I mean.”

“I don't care,” Tom said. “Anyway, you don't think those kids did this all on their own, do you? Johnny Wiggs is mixed up in it somehow. It wasn't any kid who drowned that cat. Or at any rate, they wouldn't have had the nice little idea of putting it here for you to find. If you ask me, they need to be taught a lesson. All of them. I watched you making that camp of yours.”

“Hey!” Geoffrey came jumping down from the far side of the Ditch, where he had been poking about beside the fence. “Look, I found this in the grass over there; they must have just buzzed it away. But there isn't any sign of your gun, Pete.”

He was holding their old broken spade, which had been stowed in the secret cupboard with all the rest. They had left it clean, after rubbing it carefully with handfuls of grass. Now it was caked thickly with hunks of damp mud.

Geoffrey rubbed his finger down the spade, sending down a shower of muddy flakes. He said without looking up, “UmâI thought, if we've got this to dig withâperhaps we could bury the cat.”

There was a short silence. Then Peter said briskly, “Good idea.”