Dawn of Fear (6 page)

Authors: Susan Cooper

John Brand pulled the wooden cover over the shelter entrance and tugged down the curtain that hung behind it, and Mrs. Brand lit a candle that stood waiting in a wax-scarred saucer on the shelf nailed to the corrugated metal wall. Outside, the bumps and bangs went on. Derek sat down suddenly on the bottom bunk and burst into tears.

His father sat down beside him and held him tightly. “I'm sorry, Derry. Are you all right?”

Miserably Derek nodded, unable to speak for the sobs that were sending his chest up into his throat. He pressed his head hard into his father's arm and clutched at his hand.

“I didn't mean to be rough,” John Brand said. “But you mustn't ever be outside when a raid's going on. Never. Never. You know the rules. You must always get into a shelter as quickly as you possibly can. Or if there isn't a shelter, then into a ditch, or under a tree, or anywhere close to the ground. You aren't really old enough to be frightened, and because you aren't, you just must remember the rules. Understand?”

Swallowing, choking, Derek nodded again. He said, through gulps, “I'm sorry.”

His father's arm around him was like an iron bar. He said softly, “We don't want to lose you.”

Derek looked up, blinking in the wavering yellow light of the candle, and saw Hugh watching him from wide dark eyes in the opposite bunk, and his mother sitting there silent beside him, holding his hand. She gave him a small encouraging smile, and he saw that her face was wet. “Oh, Mum,” he said unsteadily, nearly beginning again, and lurched across the shelter. “I'm sorry, Mum.”

She hugged him and wiped his face. “There now,” she said. “But you must remember what Daddy said. Always.”

“We always get down somewhere if we hear planes when we're out,” Derek said. “Even if the warning hasn't gone. Until we can see whether they're ours.”

“That's very good,” his mother said. “Now you get up into your bunk, and I'll tuck the blanket around you. We may be here for a while tonight. You close your eyes and try to get some rest. You, too, Hughie, lie down now and go to sleep.”

There was another great thump outside, and the earth gently shook. Opening his eyes, Derek saw from his bunk the jerk of the candle flame and the quiver in the thin dark line of greasy smoke that rose from it to the low curved metal roof.

“Don't worry,” his father said, watching him. “They're going away. Our battery has stopped firing. It won't be too long now.”

Derek lay there, pressing his boots against the end of the bunk; feeling the blanket rough against his chin; smelling the shelter smell of dank earth and candle grease. He thought sleepily, “But I'm not worried.” He had never been frightened by the bombs. The raids were always an excitement, though a mixed excitement because he knew going down to the shelter made Hugh's cough worse. That was the only reason for not wanting a raid: that and the camp. Like anybody else, he knew what it was like to be scared by things like the snapping of a large dog, by bigger boys chasing him at school, by being alone in the dark. But the guns and the bombs and the swooping planes, they were different. Nothing about them had ever really bothered him beforeânot, at any rate, until that fierce moment this evening, with the strange urgent note in his father's voice and the violence with which he had pulled him down. Derek gulped again at the thought of it. That had scared him all right. It was so totally out of character in his gentle father; he had never seen anything like it before. “I won't ever hang about again when we're coming down here,” he thought earnestly; “I'll get in as quick as ever I can.”

The thumping of the guns grew more muffled; merged into a familiar, almost comforting background, with Hugh's occasional cough and his parents' intermittent soft murmuring below. Derek drifted into sleep, thinking: “I hope the camp's all right. I hope they didn't get the camp.”

4

T

HE CAMP

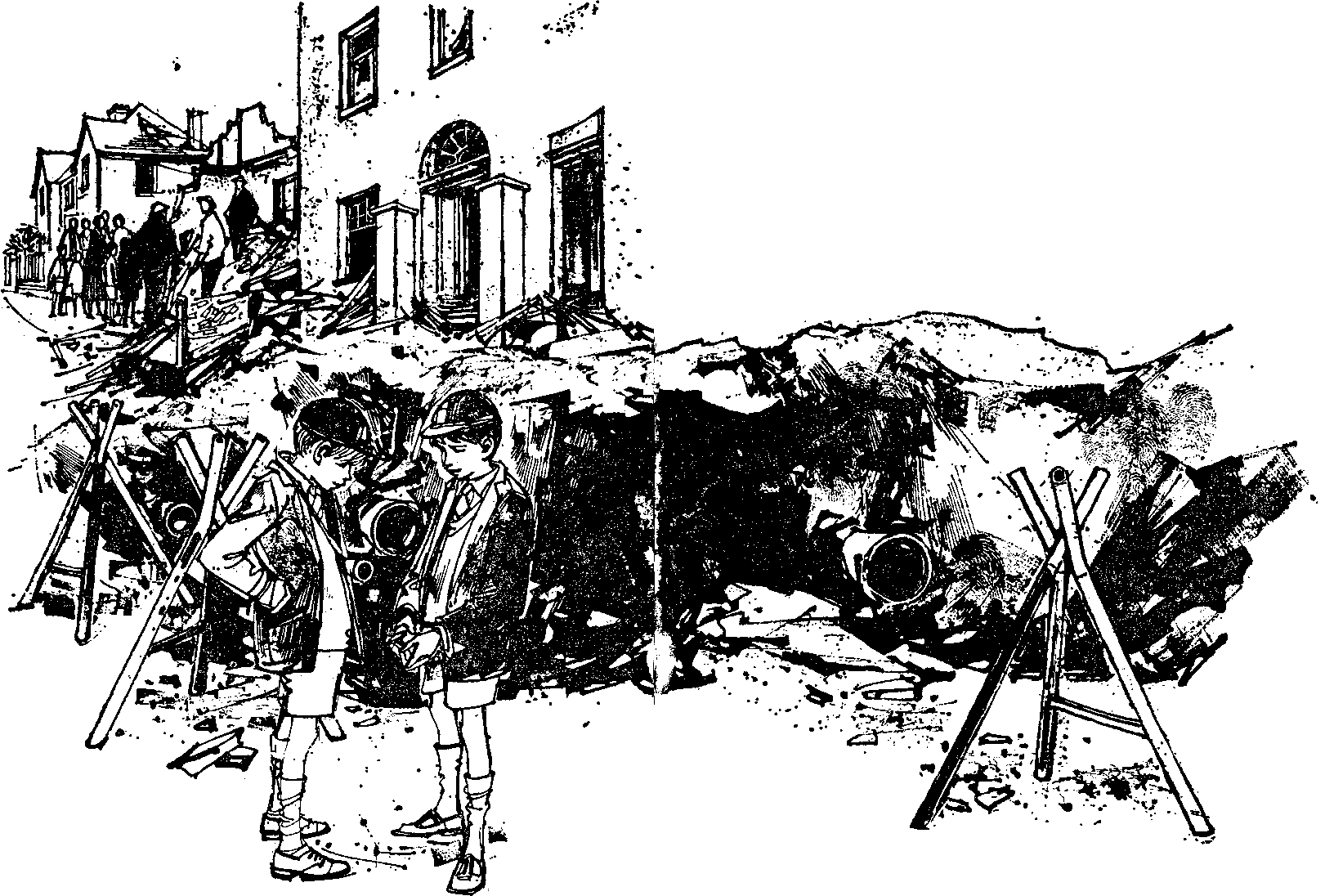

was intact. They were working on it again by the time the next morning was halfway through. The three of them had walked together to school as they always did: up Everett Avenue, across the main highway, and along the three side streets lined with gigantic metal objects like candlesticks that put up the smokescreen to protect the housing estate in a raid. As they turned the corner toward the school, they could see the crowd that told them something was wrong, and they broke into a run, with Peter in front as he always was sooner or later. Within moments they were in the thick of the crowd and gazing down at the huge gaping hole in the road outside the gates of the school.

Derek stood staring, mesmerized. He had seen bomb craters before, but they had always been in fields. A hole in a field, even a huge hole, was not the same as a hole in a road; this was more violent, somehow, with yards and

yards of road and pavement simply gone, vanished, and the road surface and stones and gravel and clay and broken pipes left naked in layers, as if by a vast jagged slice taken from a gigantic cake. When he looked around again, he saw that there was another crater close by, where the garden of the house next door to the school had been, and that there was not much house left, either, but only a heap of rubble and one lonely wall.

“The old lady was in there.” Peter was back at his side, wide-eyed from gathering reports. “The bomb fell right on the house, and she got killed. There was a whole stack of bombs, bong, bong, bong. They say he must have been just getting rid of them, Jerry that is, to get away from the fighters quicker. Nobody else got killed. They say he wasn't aiming at anything. I dunno though; I bet he was aiming at the school. I bet he was trying to hit us.”

“But it was the middle of the night,” Derek said.

“Well maybe he thought it was a boarding school.” Peter was not to be put off. “Then he could have got hundreds of us with one bomb.”

“And all he got was old Mrs. Jenkins.” Derek tried to think about old Mrs. Jenkins, who had been a familiar figure beaming out at all of them every morning and every afternoon, even though a few incorrigibles picked all her reachable roses and wrote rude words on her fence; and he found that he could not remember a line of her face, but only her cracked voice calling over the frosted path, one winter's day, “Good morning, boys.”

“I was looking for shrapnel,” Peter said. “But it's all gone. And you can't get down into the crater because they've got that rope around it. What a swizz.”

“I found a bit in the garden this morning,” Derek said.

“Did you really? Let's have a look.”

Derek reached carefully into his pocket and unwrapped the small jagged piece of metal from his handkerchief. He had found it quite by accident when kicking a pebble along the front garden path, and felt as though he had come across the Koh-i-noor diamond. Each of the boys had a handful of pieces of shrapnel recovered from bomb craters or exploded shells, but they were hard to come by; too many other people had generally gotten there first.

“That's a smashing bit,” Peter said generously. “Must be from a shell. That raid went on for ages.”

“Um,” Derek said. Usually they went over their memories of night raids in lurid and exaggerated detail, but he found himself curiously reluctant this time. He said offhandedly, “They were machine-gunning the road.”

“Yes,” Peter said. “I know.” And he, too, left it at that.

“Peter Hutchins,” said a familiar, clear voice. “Derek Brand.”

They turned and saw Mrs. Wilson stepping out of a knot of teachers close to the school gate. “Morning, ma'am,” they said.

“That

crater,

ma'am,” Peter said. “Did you know old Mrs. Jenkins got killed? Did they hit the school as well?”

Â

Â

“It was very sudden, and we must be glad poor Mrs. Jenkins didn't know what was happening,” Mrs. Wilson said gently. “And no, the school wasn't hit, but it was damaged by the blast, and we shan't be having lessons until Wednesday. Are your mothers at home?”

“Mine is,” Derek said.

“My mum's at work,” Peter said.

“Well, you'd better both go back to Derek's house. I'm sure Mrs. Brand won't mind looking after you, too, Peter.”

“She'd be very pleased, ma'am,” Derek said.

Mrs. Wilson's mouth twitched, and she patted him on the shoulder. They liked Mrs. Wilson. She was quite old, even older than their mothers, and she yelled at you and sometimes threw chalk if you made a noise in class, but she was all right, Mrs. Wilson was. They liked her. Neither of them could have explained why.

Mrs. Wilson said, “Is Geoffrey Young with you?”

Peter looked at the crowd. “He's in there somewhere.”

“His mum's at home,” Derek said.

“All right. I'll see him if you don't. But you have a look for him now, and all three of you go along home. There's nothing to see here now. And remember school starts again as usual the day after tomorrow. You don't get any more extra holiday than that, even if Jerry tried to get you one.”

They laughed, said “Thank you, ma'am; good-bye, ma'am,” found Geoffrey, and ran home. They talked about the stick of bombs all the way. To have a bomb just miss the school, now that was something. “Just suppose it had been in the daytime,” they said to one another with relish. “Just suppose we'd all been there.” And at no point did Derek link the possibility with the events and emotions and memories of the night before. They were hardly even memories now, or would not be until the

dark came down again and the air-raid warning came howling out.

Â

T

HE CAMP

was developing quickly. They carved out a hole in one side and fitted one of Peter's packing cases in to act as a cupboard; they opened the second box out to lie flat, or flattish, for a roof, banged all the protruding nails flat with a stone, dug out a deep slit in the orange clay, and fitted it in. This took a long time, not least because only two of them were ever working at once. They took turns keeping watch on the other side of the fence, safe in the back field, just in case someoneâanyoneâmight pass and see what they were doing and tell them they shouldn't be doing it.

When the roof, or part roof, was on, they stood back and surveyed the camp. It was a V-shaped room now, with two bare earth walls formed by the side and end of the Ditch. Peter and Derek packed a thin layer of earth carefully over the roof, stuffing handfuls of grass into any slits where it dribbled through, and made complicated and not very effective attempts to plant tufts of growing grass on top of it. “Camouflage,” Peter said. “Like those pictures of soldiers with branches stuck onto their tin hats.”

“Like the way they paint everything brown and greenâaircraft hangers and the factory chimneys on the estate.”

“What about the edge of the roof?” demanded Geoffrey, arriving with a critical eye from his tour on watch.

“You can't cover that. The earth just drops off.”

“Well it sticks out like anything. It's all white. You can see it miles away.”

“We can dirty it.” Peter rubbed a damp handful of clay along the bright edge. “And we can dig up some little bushes or something and plant them in front here, and they'll grow up and hide the whole thing. And we'll have a wall sticking out half the way across, so the entrance'll be between that and the other side of the Ditch.”

“With gaps on the top of it to fire over,” Derek said. “Like a castle.”

“Battlements,” said Geoffrey.

“Battlements,” Peter said thoughtfully. But nobody said anything about a battle.

They all went home to dinner. Peter's mother was at home after all; they had called in at his house on the way, to collect their packing cases, and found her. The factory where she worked had been bombed in the raid the night before. They had asked whether anyone had been killed, and she had told them abruptly to go away and play.

Geoffrey came knocking at the back door in the afternoon. “Can Derry come out, Mrs. Brand?”

Derek came out. It was a gray day, but no raid had arrived yet; the air and the breeze were still dry. “Where's Pete?” he said.

“I don't know. He wasn't there. Nobody was. I suppose his mum took him shopping.” Geoffrey brought out the idea with distaste and some scorn. To each of them a shopping trip was a shameful occupation, but he was the only one who could afford to say so. The one advantage of having two elder sisters was their endless willingness to trot off, even with no clothing coupons in their pockets, to inspect shop windows in the town to which the buses went.

“Swizz,” Derek said. In silence, they made for the camp. He never felt quite at his ease when he was alone with Geoffrey; somehow it was difficult to know what to talk about. Pete and he could be alone for hours and neither really consciously notice that the other was there; their talking was a thinking aloud. But Geoffrey was peculiar. You were always aware, in some way, that you didn't know what was going on inside his head, and sometimes he would suddenly come out with some remark that made it clear he thought there was something sinister or discreditable going on inside yours. And it was always at a time when you were just thinking about the weather or the shape of a tree or nothing at all.