Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (22 page)

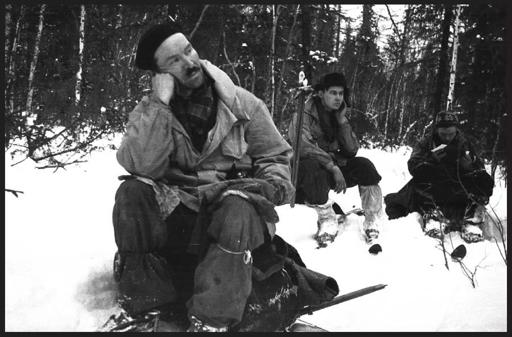

The Dyatlov hikers stop for a rest. Left to right: Alexander “Sasha” Zolotaryov, Yuri Doroshenko and Igor Dyatlov, eating “salo,” January 30, 1959.

Second day of skiing. From our night camp by the Lozva River we took the route to the night camp at Auspiya River, along a Mansi path. Weather is fine, –13°. Weak wind. There is often an ice crust on the Lozva. That’s all

.

On the third day, their trek became markedly more difficult. The temperature dropped, a southwest wind began to blow, and snow fell. What’s more, the group lost the Mansi tracks. With the benefit of an already trodden path now gone, and with the snowpack almost four feet deep in places, their progress slowed considerably. Meanwhile the forest seemed to be retreating around them. The trees thinned, and the remaining birches and pines shrank to a dwarfish size and began to appear out of the ground at crooked, windblown angles. Despite the drop in temperature, the ice on the river was still too thin to rely on:

It’s impossible to go over the river, it’s not frozen. Water and ice crust are under the snow right on the ski track, so we go near the shore again

.

Though they had lost the Mansi’s path, the hikers continued to find symbols among the dwindling trees. As the group’s diary records, they talked increasingly of the native people.

Mansi, Mansi, Mansi. This word becomes more frequent in our talks. Mansi are people of the North. . . . It’s a very interesting and peculiar nation living in northern Urals, close to Tyumen region

.

Zina was particularly fascinated by the tribal symbols and stopped to copy some of them in her diary.

The Dyatlov hikers travel up the Lozva River. Front to back: Nikolay “Kolya” Thibault-Brignoles, Alexander “Sasha” Zolotaryov, and Lyudmila “Lyuda” Dubinina (left), January 30, 1959.

Maybe the title of our trip should be “In the land of mysterious signs.” If we knew their meaning, we could follow the path without worrying that it might take us in the wrong direction

.

After a late afternoon meal of leftovers from breakfast—brisket, dried bread, sugar, garlic, coffee—they continued on for another few hours before stopping for the night. But with the landscape increasingly exposed, the group had to double back over 200 yards to find a suitable spot surrounded by tall, dry trees. It had been a difficult day, perhaps the most difficult yet, and for some among the group, tempers were short. An argument erupted between Lyuda and Kolya concerning one of their chores. Zina bore witness to the episode:

So they argued for a long time about who should stitch the tent. At last [Kolya] gave up and took a needle. Lyuda remained sitting. And we were fixing holes (so many holes that everyone had plenty to do. . . . The guys are awfully indignant

.

Later that night, the mood brightened as the group gathered around an outdoor fire to celebrate Doroshenko’s twenty-first birthday. They presented him with a gift that had been stowed away for the occasion: a tangerine. Tangerines had been available in the Soviet Union since the 1930s when they began to be shipped north from the Abkhazia citrus plantations near the Black Sea. They were a special fruit available only for a brief season, and because of their aura of novelty, they were often given as gifts around New Year’s Day. But instead of enjoying his present, Doroshenko insisted on dividing the tangerine equally among his friends. Only Lyuda missed out on the treat, as she was still stinging from the earlier argument and had sequestered herself in the tent. Zina wrote: “Lyuda had gone inside the tent and didn’t appear till the end of dinner.” But Zina ended her diary entry on an optimistic, if cautious, note: “So, one more day passed by safely.”

The next day, January 31, would be the final day documented in the group’s journals. The hikers often wrote their diary entries in the mornings, which meant that they were writing about events of the previous day. Of the last day in January, Igor noted that the group set out at 10:00

AM

, and that the weather had immediately worsened with an aggressive wind blowing in from the west. The sky was clear, yet it was inexplicably snowing—but, as Igor noted, the precipitation was most likely an illusion caused by the wind sweeping snow from the treetops.

It was on this second-to-last day of their trip that the nine hikers began to deviate from the river and make their way up the slope in the direction of Otorten Mountain. The group had been

lucky in rediscovering the Mansi tracks—ski tracks this time—but the uphill path was still slow going and the hikers needed a more efficient method of cutting through the snow. They invented one on the spot, one that Igor called “path-treading,” in which the lead hiker takes off his backpack and beats a path for five minutes before returning to his pack to rest. When he has retrieved his pack, he catches up with the others who have since flattened the path. At the end of the path, they repeat the process with a new leader. Still, even with this method, Igor noted that it was difficult to advance.

The track is hardly visible, we lose it often or walk blindly, so we cover only 1.5 to 2 km in an hour

.

Of the wind blowing in their faces, he wrote:

The wind is warm and piercing, blows fast like air when a plane takes off

.

The hikers were understandably exhausted, and at 4:00

PM

they began to look for a place to set up camp. They went south to the Auspiya valley where the wind was weak and the snow less deep. The downside to the valley was that firewood was scarce, with mostly damp firs at hand. With what firewood they could gather, they chose not to dig a fire pit and simply laid the fire on top of some logs. They ate dinner inside the tent, inspiring Igor to write, in what would be the group’s final diary entry:

It’s hard to imagine such a cozy place anywhere at the ridge, under the piercing howls of the wind, and hundreds of km from any settlements

.

FEBRUARY 1

THE FRIENDS TOOK APPROXIMATELY TEN PHOTOGRAPHS

on their final day of life, and judging from the first few snapshots taken at the campsite that morning, spirits were high. A casual shot of Kolya and Doroshenko reveals them laughing in front of the tent, surrounded by piles of backpacks. Then there are two images of Rustik, wearing a jacket that looks to have been shredded violently. Upon closer inspection, however, it appears that the material was burned, perhaps when left too close to the stove. If Rustik was worried about losing a much-needed layer of warmth, he doesn’t show it in these photographs, and instead adopts a pose of inflated pride. After all, of the nine hikers, Rustik would have been most able to afford a replacement jacket when he got home.

The morning’s mood was evidently contagious, and one member of the group drafted the front page of a mock newspaper called

The Evening Otorten

, dated February 1, Issue 1. Among its contents was an editorial posing the question, “Is it possible to keep nine hikers warm with one stove and one blanket?” plus an announcement for a daily seminar titled “Love and Hiking” to be held in the tent by lecturers “Dr.” Kolya and “Candidate of Science” Lyuda. The sports page announced that “Comrades Doroshenko and Zina Kolmogorova set a new world record in competition for stove assembly,” while the science pages claimed that the “snow man,” or yeti, dwelled in the northern Urals around Otorten Mountain.

With the morning’s entertainment out of the way, a serious task lay ahead: constructing a

labaz

, or temporary storage shelter. The hikers’ packs needed to be as light as possible for their journey up the mountain, and items that weren’t crucial for the next two days had to be stowed for their return trip. After the shelter’s construction, the hikers stocked it with food reserves, extra skis and boots, a spare first aid kit, and—most painfully—Georgy’s mandolin. Between selecting items for the shelter and stowing firewood for the night of their return, a significant portion of the morning was gone; and, after the shelter was secure, they were eager to push ahead.

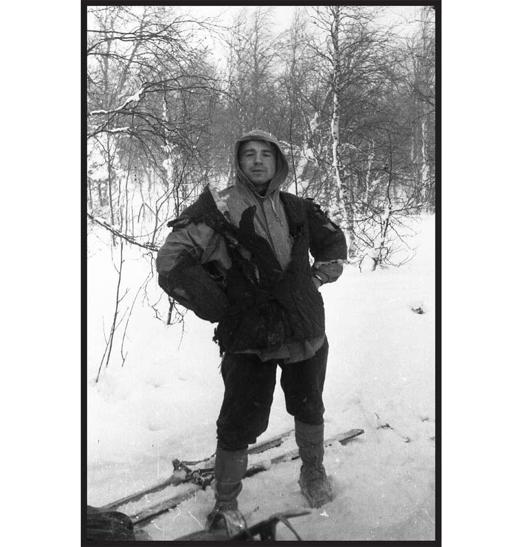

Rustem “Rustik” Slobodin shows off his burned jacket. Perhaps he left it to dry too close to the fire the previous night, January 31, 1959.

Alexander Kolevatov (left) and Nikolay “Kolya” Thibault-Brignoles share a laugh at the campsite on the morning of January 31, 1959.