Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (3 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

My investigative synapses really started to fire when I learned that the single surviving member of the Dyatlov group, Yuri Yudin, was still alive. Yudin had been the tenth member of the hiking group, until he decided to turn back early from the expedition. Though he couldn’t have known it at the time, it was a decision that would save his life. It must also, I imagined, have left him with a chronic case of survivor’s guilt. I calculated that Yudin would now be in his early to mid-seventies. And though he rarely talked to the press, I wondered: Could he be persuaded to come out of his seclusion?

Although my initial efforts to find Yudin got me nowhere, I was able to make contact with Yuri Kuntsevich, the head of the Dyatlov Foundation in Yekaterinburg, Russia. Kuntsevich explained that the foundation’s mission was both to preserve the memories of the hikers and to uncover the truth of the 1959 tragedy. According to Kuntsevich, not all the files from the Dyatlov case had been made public, and the foundation was hoping to persuade Russian officials to reopen the criminal investigation. Speaking through a translator, he was perfectly cordial and offered that he might have information to help my understanding of the incident. However,

my specific queries about the case—including how to reach Yuri Yudin—resulted in only vague or cryptic responses. At last he put the onus on me: “If you seek the truth in this case, you must come to Russia.”

Kuntsevich had no real idea who I was—I had introduced myself as a filmmaker and we’d spoken for forty-five minutes—yet he had extended an unambiguous invitation. Or was it a summons? I was not Russian. I didn’t speak the language. I had seen snow less than a dozen times in my life. Who was I to go roaming through Russia in the middle of winter to unravel one of the country’s most baffling mysteries?

As I approached Dyatlov Pass more than two years later, pausing every so often to blow warm air into my gloves, I found myself asking the same question: Why am I here?

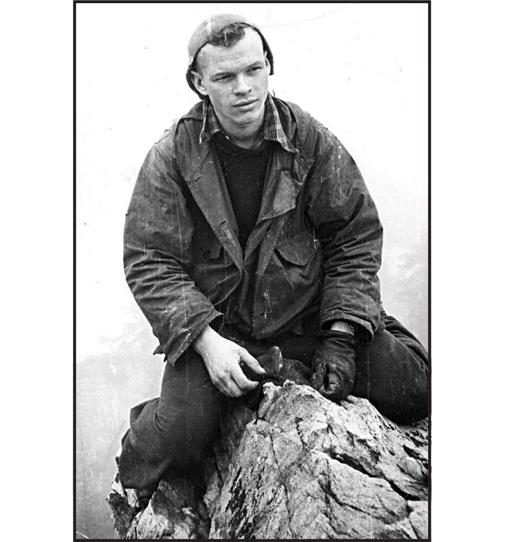

Igor Dyatlov, ca. 1957–1958

2

JANUARY 23, 1959

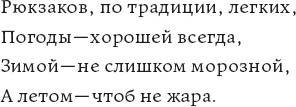

Let your backpacks be light,

weather always fine,

winter not too cold,

and summer without heat

.

—Georgy Krivonishchenko, excerpt from New Year’s poem, 1959

IF ONE HAD BEEN ABLE TO GLIMPSE INSIDE DORMITORY

531 on January 23, 1959, one would have seen the very picture of fellowship, youth, and happiness. The room itself was nothing to look at. Like most dorms at Sverdlovsk’s Ural Polytechnic Institute, the furnishings were serviceable at best; and, for half the year, the building rumbled under the toil of a coal-stoked boiler. One might have assumed in observing the room—with its blistered wallpaper, lumpy mattresses and lingering odors from the communal kitchen—that the students residing here must take pleasure in things outside material comforts. They must certainly

live for books, art, friends and nature, interests that could carry them beyond this dingy cupboard. And one would be right. On that fourth Friday in January, a month before the school term was to begin, nine friends in their early twenties were engaged in last-minute preparations for a trip that would take them far beyond the confines of dormitory life.

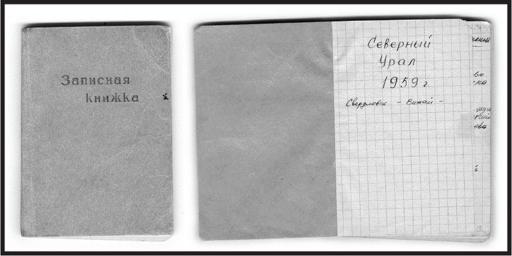

The front cover and first page of the Dyatlov group’s diary.

The room that evening was charged with excitement, each member of the group busy with a designated task and each talking over the others in an eagerness to be heard. Their group diary captured snatches of their conversation:

We’ve forgotten salt!

Igor! Where are you?

Where’s Doroshenko, why doesn’t he take 20 packages?

Will we play mandolin on the train?

Where are the scales?

Damn, it does not fit in!

Who has the knife?

One of the young men stuffed food into a backpack, trying to find the most space-efficient configuration for multiple bags of oats and cans of meat. Nearby, his friend catalogued medicines. Another searched desperately for mislaid footwear.

Where are my leather boots?

The group’s twenty-three-year-old leader, Igor Dyatlov, was overseeing these final preparations with somber concentration. Igor was lean and strong, with a head of closely cropped hair. His mouth was almost feminine, and his eyes wide set. He wasn’t classically handsome, yet there was something arresting about his face, something expressive that spoke of a rich interior life and strong self-possession. He was famous at the school’s hiking club for his technical know-how and the easy command he took over any situation. “Igor had indisputable authority,” remembered his friend and hiking mentor Volodya Poloyanov years later. “Everyone wanted to go on a trip under his leadership, but one had to earn the honor to get in Igor’s group.”

Igor had been born into a family of engineers and at an early age had shown a finely tuned, scientific mind. He was studying radio engineering at UPI, and despite the official Soviet ban on shortwave radio transmissions during the Cold War, his bedroom at home was outfitted with radio panels, homemade receivers, and a shortwave radio. “Thanks to Igor, we had a handmade radio receiver on our hiking trips,” Poloyanov said. “His technical knowledge was encyclopedic.” Another hiking friend, Moisey Akselrod, recalled of a 1958 trip to the Sayan Mountains in southern Siberia, “Dyatlov’s major contribution was his amazing ultrashortwave transmitters that were used for communications between rafts.”

Despite Igor’s affection for wireless devices, he would not be packing a radio for this particular trip. Shortwave radios of the time

were cumbersome, and hauling them into the Russian wilderness in winter would have been out of the question. Besides, Igor had his hands full ensuring his group packed the essentials. If they were to forget something, there would be no stopping for extra supplies in the middle of the Ural Mountains, and no one wanted to be responsible for neglecting to pack something potentially lifesaving. This was a pivotal trip for Igor and his friends. They were all Grade II hikers, but if this particular excursion went as planned, the group would be awarded Grade III certification upon their return. It was the highest hiking certification in the country at the time, one that required candidates to cover at least 186 miles (300 kilometers) of ground, with a third of those miles in challenging terrain. The minimum duration of the trip was to be sixteen days, with no fewer than eight of those spent in uninhabited regions, and at least six nights spent in a tent. If the hikers met these conditions, their new certification would allow them to teach others their craft as Masters of Sport. It was a distinction that Igor and his group badly wanted.

Nearby, scribbling in her diary, sat one of the two women in the room—Zinaida Kolmogorova. Like Igor, she was a student of radio engineering, though the subject didn’t come as naturally to her as it did him. To her friends, “Zina” was regarded as lively and bright, always ready with an amusing remark or engaging story. But at that moment the pretty tomboy was silent. Having been appointed the diarist for that evening, she felt obliged to record the last moments of preparation for the collective records. Her finely sculpted face and large, brown eyes were tilted toward the page, intent on capturing the mood of departure. How to describe the room?

The room is in artistic disorder

. . . . Zina was the type of girl who drew admiration wherever she went. In fact, several of her companions had secret crushes on her.

Lyudmila Dubinina, or “Lyuda,” was the other woman in the room and at twenty years old, the youngest of the group. She was a student of construction-industry economics and was a serious person, a quality evident in her assigned duty that evening: counting the money and rolling it tightly into a waterproof can. Lyuda was strong, and capable of enduring intense pain and discomfort. On a previous hiking trip, she had been shot in the leg after a companion mishandled a hunting rifle. Though she had to be carried out of Siberia’s Eastern Sayan Mountains over 50 miles of rugged terrain, she kept her companions in good spirits the entire journey.

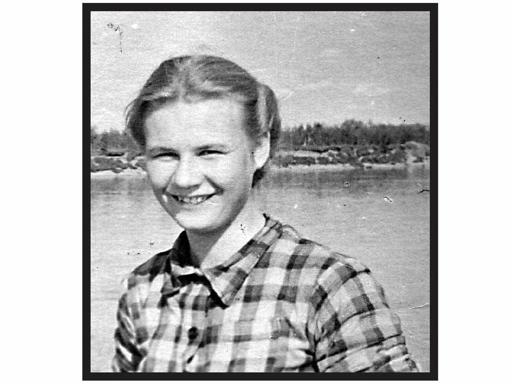

Lyudmila “Lyuda” Dubinina taken during a summer hiking tour, n.d.