Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (5 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

In the mid- to late-’50s, for the first time in decades, young Russians felt a renewed sense of promise—sports, the arts, technology and accessible education were all part of this new optimism. It was a hopeful period that wouldn’t recur in Russian history until the fall of the Soviet Union some three decades later. By Soviet standards, the Thaw was an exhilarating time to be young, physically fit and intellectually curious. The ten members of the Dyatlov group were all of these.

IT IS IN THIS YEAR OF CULTURAL FLOWERING, 1959, ON

a day in February, that Igor Dyatlov’s younger sister, Rufina, is leaving campus. At twenty-one years old, she is a pretty version of her brother, with a penetrating gaze and the well-defined bone structure found often in Slavic faces. The siblings are close and share a passion for science and technology. Rufina is, in fact, following Igor’s example by majoring in radio engineering at UPI.

Mid-February is the time of year when campus fills up with students recently returned from home or—in the case of the sports club—hiking expeditions. By now most of the hiking groups have returned in time for the new term, their young minds and lungs invigorated by the recent weeks spent in crisp mountain air. But Rufina’s brother is not among the returned. In fact, Rufina has just come from a frustrating meeting at the administrative building. It is February 16, three days after Igor was due home, and no one seems particularly worried.

Perhaps the university’s lack of concern is due to the hiking commission’s having thoroughly checked the soundness of Igor’s proposed route. Or maybe it’s because delays are routine in the

world of mountaineering, particularly in winter. With no way for the hikers to communicate with their hometown—aside from the occasional telegram sent from an outpost—should they run up against delays, there is little for their families to do but wait.

Rufina is not looking forward to informing her family that her errand at the university has failed. Perhaps she will keep the news from her twelve-year-old sister, Tatiana, who is still so young and very attached to her older brother. Tatiana needn’t know that the school administrators were unsympathetic to Rufina’s pleas, and that they had given her only noncommittal responses and baseless assurances. A group of student hikers is missing, Rufina thinks, and no one outside the hikers’ families seems to care. Not that she didn’t detect a degree of unease among the members of the UPI sports club, but most everyone seems to agree that Igor, their hiking star, and his companions are simply late. Delays happen. All it takes is one hiker to sprain an ankle and the progress of the entire group slows to a hobble.

But Rufina knows her brother and is familiar with his strengths as an outdoorsman. Igor, in the fashion of their older brother, Slava, is a

tourist

—though not in the Western sense of the word. A

tourist

in the Russian sense is much closer to

adventurer

: a hiker or skier who journeys into the wilderness to explore new territory and push past personal limits of endurance. And Igor, in the eyes of his fellow hikers, is a

tourist

of the highest magnitude. But where his classmates at the hiking club see this as reason to expect his return, Rufina only finds more cause for worry. If a man as capable and careful as her brother hasn’t returned by now, she reasons, it could only mean that something is very wrong.

Rufina thinks back to Igor’s previous trips, searching for some kind of precedent for his absence. She thinks of his love of nature and photography, and how his strong visual talents informed his entire approach to nature. His deep love of the outdoors was evident in the way he wrote about his hiking trips in his journals.

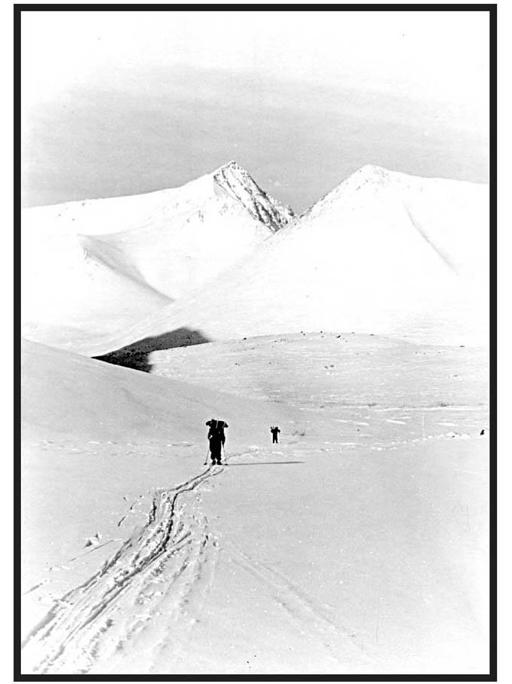

Photo taken by Igor Dyatlov, 1958.

July 8. We are in a beautiful meadow, walking along blossoming willow-weed, chamomile, and bluebell. The grass is high, so we walk in single file. The flat, expansive meadow is surrounded by hills, and far away we can see the bluish foothills of the Ural Mountains. The air is warm, the smell of grass is intoxicating, and the birds are chirping

—

what a dream!

Most of the journal entries from Igor’s trips read this way: tranquil, with a deep appreciation for the plant and animal life of the Urals. There might have been trips during which her brother was caught by surprise by some unforeseen danger, but there had been nothing he wasn’t capable of handling. There was that trip a couple summers ago when Igor and his friends encountered a herd of wild horses, an incident documented in the group’s journal:

Suddenly from behind comes a powerful roar, of some unknown origin but approaching very quickly. We look back and freeze in terror: heading toward us is a herd of wild horses

—

many, many of them, a whole bunch! The first thought is run! But where to?! Igor commands firmly: “Stop! Nobody move!” We gather in a tight group, some covering their eyes, others with eyes wide open in horror, watching in complete silence the herd of about thirty horses racing towards us at full speed! About fifteen meters before they smash into us, the herd suddenly splits into two and, without slowing down, streams around us, like the river around a rock, and continues on its way

.

But summer in the Ural Mountains presents an entirely different set of dangers from those of winter. Rufina knows that winter hiking is far more perilous than hiking in any other season, and that the sooner the university begins to look for her brother, the better her family’s chances of bringing him home safe.

IGOR DYATLOV’S FAMILY IS NOT ALONE IN THEIR UNEASE

. On February 13, the day of the Dyatlov group’s appointed return, and in the days following, family members of the hikers begin to express their worry. The parents of Rustik Slobodin are the first to express outward concern. Rustik’s father, Professor Vladimir Slobodin, who teaches at a local agricultural university, phones the UPI Sports Club, at which point he is informed that Lev Gordo, the middle-aged director of the club, is himself on a trip and won’t be returning for several days. Until Gordo returns, the professor is told, little can be done.

As two more days pass, the university’s telephones ring with repeated calls from nervous relatives. They are told variations of the same thing: The Dyatlov group is delayed, the president of

the club is absent, nothing can be done at the moment, please be patient. But for the parents of the hikers, assurances from the sports club mean little in the conspicuous absence of their children, and they stay close to the phone. On February 17, bowing to pressure, university officials send an inquiring telegram to Vizhay, the village from which the Dyatlov group would be traveling. Meanwhile, the families make a request to the university for search planes. The request is refused.

The following day, club director Lev Gordo returns from his dacha to discover the tempest that has been brewing in his absence. But today, the university is in a position to give the families information, though not the information they are hoping for. A reply telegram has come from Vizhay: “The Dyatlov group did not return.”

This turns out to be the necessary incitement for the university to take action, and a Colonel Georgy Ortyukov, a lecturer of reserve-officer training at UPI, takes charge of assembling a formal search party for the missing hikers. Lev Gordo, meanwhile, together with UPI student Yuri Blinov—whose group had shadowed Dyatlov’s on the first leg of their trip—is assigned to travel the following day to Ivdel, the gateway to the northern Urals.

But the search party’s efforts are stymied before they’ve begun: The Dyatlov group’s approved route is nowhere to be found at the local hiking commission. Either the route has been lost or was never filed. Though their general destination north is known, there is no way to know precisely which route they took within those mountains. Without a definitive map of the hikers’ course, the search party might as well be stepping into the Russian wilderness half blind.

On Friday, February 20, the search for the missing hikers officially begins. Gordo and Blinov fly out from Sverdlovsk by military helicopter and arrive later that day in Ivdel. From there, they take a Yak-12 surveillance plane north toward Vizhay, up the Lozva River, over an abandoned mine, and past Sector 41—a cluster of log cabins populated by woodcutters. The plane then veers west to

the Severnaya Toshemka River, where the pair scan the Ural ridge and western Ural slopes. But before they can get far, clouds and strong winds force them to turn back to the airfield for the night.

On the same day Gordo and Blinov are scanning the northern Urals by air, UPI student Yuri Yudin has returned to Sverdlovsk for the new school term. Because he was assumed to be among Igor Dyatlov’s group, his peers are surprised to see his face, and he is put in the position of explaining his peculiar non-absence. During the trip, Yudin’s chronic back pain had reached incapacitating levels, forcing him to turn back early. But instead of returning directly to Sverdlovsk, Yudin had taken a detour to spend the rest of winter break in his home village of Emelyashevka, about 150 miles northeast of Sverdlovsk. There, he took his time and enjoyed the company of his family, unaware of what was happening back at school.

Now, upon his return to campus, Yudin is surprised to learn that his friends have not returned. He knows Igor and the rest were running three days behind, a fact Yudin now realizes he forgot to relay by telegram to the university. Now the original three days of delay has become six. But Yudin is not yet convinced this is cause for alarm, and on his first day back at school, he buries himself in his geology studies and puts his friends out of his mind. Perhaps he believes he is partly to blame for all the fuss. If he had only communicated the Dyatlov party’s delay in the first place, he might have saved the university all this worry. It will be several days before Yudin begins to register his own alarm.

The next day Gordo and Blinov are in the air again, the weather has greatly improved since the previous day. They fly to the Vizhay riverhead and over the Anchucha tributary, which is the territory of the region’s indigenous people: the Mansi. Along with a neighboring tribe, the Khanty, the Mansi occupy sections of the Urals and northwestern Siberia. Their numbers are small, around 6,400, and they live in villages whose economies revolve around hunting, fishing and the herding of reindeer.