Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1349 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

By 3:45 A.M. the first objective had been taken, and by five the second, save in front of the Leinsters, where there was a stout resistance at a German machine-gun post, which was at last overcome. It was at this period that a dangerous gap developed between the retarded wing of the right-hand brigade and the swiftly advancing flank of the left, but this opening was closed once more by seven o’clock. By 7:30 the third objective had been cleared by the 1st Munsters on the right and the 2nd Irish Rifles on the left, for the second line had now leap-frogged into the actual battle. By eight o’clock everything had fallen, and the field-guns of the 59th and 113th Brigades R.F.A. had been rushed up to the front, well-screened by the slope of the newly conquered hill. The new position was swiftly wired by the 11th Hants and Royal Engineers.

There now only remained an extreme line which was, according to the original plan, to be the objective of an entirely new advance. This was the Oostaverne Line, so called from the hamlet of that name which lay in the middle of it. Its capture meant a further advance of

The enemy had been dazed by the terrific blow, but late in the evening signs of a reaction set in, for the German is a dour fighter, who does not sit down easily under defeat. It is only by recollecting his constant high qualities that one can appreciate the true achievement of the soldiers who, in all this series of battles — Arras, Messines, and the Flanders Ridges — were pitch-forking out of terribly fortified positions the men who had so long been regarded as the military teachers and masters of Europe. Nerved by their consciousness of a truly national cause, our soldiers fought with a determined do-or-die spirit which has surely never been matched in all our military annals, while the sagacity and adaptability of the leaders was in the main worthy of the magnificence of the men. As an example of the insolent confidence of the Army, it may be noted that on this, as on other occasions, all arrangements had been made in advance for using the German dumps. “This should invariably be done,” says an imperturbable official document, “as the task of rapidly getting forward engineer stores is most difficult.”

A line of mined farms formed part of the new British line, and upon this there came a series of German bombing attacks on June 8, none of which met with success. The 68th Field Company of the Engineers had inverted the position, turning the defences from west to east, and the buildings were held by the Lincolns and Sherwoods, who shot down the bombers before they could get within range even of the far-flying egg-bomb which can outfly the Mills by thirty paces, though its effect is puny in comparison with the terrific detonation of the larger missile. From this time onwards, the line became permanent. In this long day of fighting, the captures amounted to 8 officers and 700 men with 4 field-guns and 4 howitzers. The losses were moderate for such results, being 1100 men for the Irish and 500 for the 33rd Brigade. Those of the Ulster Division were also about 1000.

Upon the left of the Irishmen the advance had been carried out by Shute’s Nineteenth Division. Of this hard fighting division, the same which had carried La Boiselle upon the Somme, the 56th Lancashire Brigade and the 58th, mainly Welsh, were in the line. The advance was a difficult one, conducted through a region of shattered woods, but the infantry cleared all obstacles and kept pace with the advance of the Irish upon the right, finally sending forward the reserve Midland Brigade as already stated to secure and to hold the Oostaverne Line. The ground to be traversed by this division, starting as it did from near Wulverghem, was both longer and more exposed than that of any other, and was particularly open to machine-gun fire. Without the masterful artillery the attack would have been an impossibility. None the less, the infantry was magnificently cool and efficient, widening the front occasionally to take in fortified posts, which were just outside its own proper area. The 9th Cheshires particularly distinguished itself, gaining part of its second objective before schedule time and having to undergo a British barrage in consequence. This fine battalion ended its day’s work by blowing to shreds by its rifle-fire a formidable counter-attack. The Welsh battalions of the same 58th Brigade, the 9th Welsh Fusiliers, 9th Welsh, and 5th South Wales Borderers fought their way up through Grand Bois to the Oostaverne Line with great clash and gallantry. The village of that name was itself taken by the Nineteenth Division, who consolidated their line so rapidly and well that the German counter-attack in the evening failed to make any impression. Particular credit is due to the 57th Brigade, who carried on the attack after their own proper task was completed.

We have now roughly sketched the advance of the Ninth Corps, and will turn to Morland’s Tenth Corps upon its left. The flank Division of this was the Forty-first under the heroic leader of the old 22nd Brigade at Ypres. This unit, which was entirely English, and drawn mostly from the south country, had, as the reader may remember, distinguished itself at the Somme by the capture of Flers. It attacked with the 122nd and 124th Brigades in the line. They had several formidable obstacles in their immediate front, including the famous Dammstrasse, a long causeway which was either trench or embankment according to the lie of the ground. An estaminet upon this road was a lively centre of contention, and beyond this was Ravine Wood with its lurking guns and criss-cross of wire.- All these successive obstacles went down before the steady flow of the determined infantry, who halted at their farthest line in such excellent condition that they might well have carried the attack-forward had it not been prearranged that the Twenty-fourth, the reserve division, should pass through their ranks, as will presently be described.

To the left of the Forty-first was the Forty-seventh London Territorial Division containing the victors of Loos and of High Wood. The effect of the mines had been particularly deadly on this front, and one near Hill 60 is stated by the Germans to have taken up with it a whole Company of Wurtembergers. The position attacked by the Londoners was on each side of the Ypres-Comines Canal, and included some formidable obstacles, such as a considerable wood and a ruined country-house named “The White Château.” Again and again the troops were held up, but every time they managed to overcome the obstacle. Around the ruined grandeur of the great villa, with all its luxuries and amenities looking strangely out of place amid the grim trimmings of rusty wire and battered cement, the Londoners came to hand-grips with the Prussians and Wurtembergers who faced them. In all 600 prisoners were sent to the rear.

To the left of the Forty-seventh London division, and forming the extreme flank of the attack, was the Twenty-third Division (Babington) of Contalmaison fame, a unit which was entirely composed of tough North of England material. It was in touch with the regular Eighth Division upon the left, this being the flank division of the Fifth Army. The latter took no part in the present advance, and the Twenty-third had the task of forming a defensive flank in the Hooge direction, while at the same time it attacked and conquered the low ridges from which the Germans had so long observed our lines, and from which they had launched their terrible attack upon the Canadians a year before. No long advance was expected from this division, since the object of the whole day’s operations was to flatten out an enemy salient, not to make one upon our own side. Sufficient ground was occupied, however, to cover the advance farther south, and without this advance it would have been impossible for the supporting division to carry on, without exposing its flank, the work which had been done by the two divisions upon the right. At 3:10 in the afternoon, the Twenty-fourth Division under General Bols, an officer whose dramatic experience in the La Bassé fighting of 1914 has been recounted in a previous volume, advanced through the ranks of the Forty-first and Forty-seventh Divisions at a point due east of St. Eloi, its attack being synchronised with that upon the Oostaverne line farther south. The operation was splendidly successful, for the 73rd Brigade upon the left and the 17th upon the right, at the cost of about 400 casualties, carried that section of the Dammstrasse and the whole of the historic, blood-sodden ground upon either side of it, so rounding off the complete victory of the Second Army. So close to the barrage was the advance of the infantry, that the men of the 1st Royal Fusiliers and 3rd Rifle Brigade, who led the 17th Brigade, declared that they had the dust of it in their faces all the way.

It only remains to be added that on the extreme left of the line the Germans attempted a counter-attack while the main battle was going on. It was gallantly urged by a few hundred men, but it was destined to complete failure before the rifles of the 89th Brigade of the Thirtieth Division (Williams). Few of these Germans ever returned.

It was a one day’s battle, a single hammer-blow upon the German line, with no ulterior operations save such as held the ground gained, but the battle has been acclaimed by all critics as a model and masterpiece of modern tactics, which show the highest power of planning and of execution upon the part of Sir Herbert Plumer and his able Chief-of-Staff. The main trophy of course was the invaluable Ridge, but in the gaining it some 7200 prisoners fell into British hands, including 145 officers, which gives about the same proportion to the length of front attacked as the Battle of Arras. The Germans had learned wisdom, however, as to the disposition of their guns in the face of “the unwarlike Islanders,” so that few were found within reach. Sixty-seven pieces, however, some of them of large calibre, remained in possession of the victors, as well as 294 machine-guns and 94 trench mortars. The British losses were about 16,000. The military lesson of the battle has been thus summed up in the words of an officer who took a distinguished part in it: “ The sight of the battle-field with its utter and universal desolation stretching interminably on all sides, its trenches battered out of recognition, its wilderness of shell-holes, debris, tangled wire, broken rifles, and abandoned equipment, confirms the opinion that no troops, whatever their morale or training, can stand the fire of such overwhelming and concentrated masses of artillery. With a definite and limited objective and with sufficient artillery, complete success may be reasonably guaranteed.” It is the big gun then, and not, as the Germans claimed, the machine-gun which is the Mistress of the Battle-field. The axiom laid down above is well proved, but it works for either side, as will be shown presently where upon a limited area the weight of metal was with the Germans and the defence with the British.

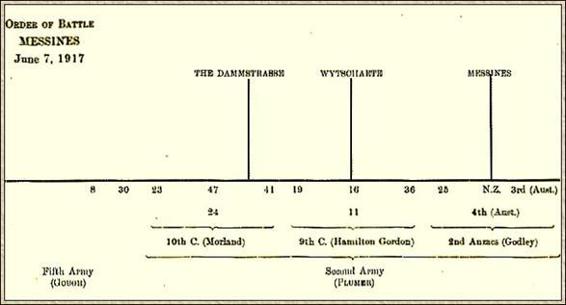

Order of Battle, Messines, June 7, 1917

So fell Messines Ridge. Only when the British stood upon its low summit and looked back upon the fields to westward did they realise how completely every trench and post had been under German observation during these years. No wonder that so much of the best blood of Britain has moistened that fatal plain between Ypres in the north and Ploegstrate in the south. “My God!” said an officer as he looked down, “it is a wonder that they let us live there at all.” “It is great to look eastwards,” said another, “and see the land falling away, to know that we have this last height and have wrested it from them in three hours.” It was a nightmare which was lifted from the Army upon June 7, 1917.

V. OPERATIONS FROM JUNE 10 TO JULY 31

Fighting round Lens — Good work of Canadians and Forty-sixth Division — Action on the Yser Canal — Great fight and eventual annihilation of 2nd K.R.R. and 1st Northamptons — An awful ordeal — Exit Russia

THE Battle of Messines was so complete and clean-cut within its pre-ordained limitations that it left few readjustments to be effected afterwards. Of these, the most important were upon the left flank of the Anzac Corps, where, as already narrated, some Germans had held out for some days in the gap left between the two forward brigades of the Fourth Australians. These were eventually cleared out, and upon the night of June 10 the 32nd Brigade of the Eleventh Division extended the front of the Ninth Corps to the south, and occupied all this sector, which had become more defensible since, by the energy and self-sacrifice of the 6th South Wales Borderers, a good road had been driven right up to it by which stores and guns could proceed.

It was determined to move the line forward at this point, and for this purpose the Twenty-fifth Division was again put in to attack, with the 8th Borders on the left and the 2nd South Lanes on the right, both of the 75th Brigade. The objective was a line of farmhouses and strong posts immediately to the east. The men were assembled for the attack in small driblets, which skirmished forward and coalesced into a line of stormers almost unseen by the enemy, crouching behind hedges and in the hollows of the ground. At 7:30 in the evening, before the Germans realised that there had been an assembly, the advance began, while the New Zealanders, who had executed the same manoeuvre with equal success, kept pace upon the right. The result was a complete success within the limited area attacked. The whole line of posts, cut off from help by the barrage, fell into the hands of the British in less than half-an-hour. The enemy was found lying in shell-holes and improvised trenches, which were quickly cleared and consolidated for defence. After this second success, the Twenty-fifth Division was drawn out, having sustained a total loss of about 3000 during the operations. Their prisoners came to over 1000, the greater number being Bavarians.

For a time there was no considerable action along the British line, but there were large movements of troops which brought about an entirely new arrangement of the forces, as became evident when the operations were renewed. Up to the date of the Battle of Messines the Belgians had held the ground near the coast, and the five British Armies had lain over their hundred-mile front in the order from the north of Two, One, Three, Five, and Four. Under the new arrangement, which involved a huge reorganisation, it was the British Fourth Army (Rawlinson) which came next to the coast, with the Belgians upon: their immediate right, and an interpolated French army upon the right of them. Then came Gough’s Fifth Army in the Ypres area, Plumer’s Second Army extending to the south of Armentières, Horne’s First Army to the south end of the Vimy Ridge, and Byng’s Third Army covering the Cambrai front, with dismounted cavalry upon their right up to the junction with the French near St. Quentin. Such was the general arrangement of the forces for the remainder of the year.

Save for unimportant readjustments, there were no changes for some time along the Messines front, and little activity save at the extreme north of that section on the Ypres-Comines Canal. Here the British gradually extended the ground which had been captured by the Forty-seventh Division, taking some considerable spoil-heaps which had been turned into machine-gun emplacements by the Germans. This supplementary operation was brought off upon June 14 and was answered upon June 15 by a German counter-attack which was completely repulsed. Some brisk fighting had broken out, however, farther down the line in the Lens sector which Holland’s First Corps, consisting of the Sixth, Twenty-fourth, and Forty-sixth Divisions, had faced during the Battle of Arras. This sector was rather to the north of the battle, and the German line had not been broken as in the south. These divisions had nibbled their way forward, however, working up each side of the Souchez River until they began to threaten Lens itself. The Germans, recognising the imminent menace, had already blown up a number of their depots and practically destroyed everything upon the surface, but the real prize of victory lay in the coal seams underground. Huge columns of black smoke which rose over the shattered chimneys and winding gears showed that even this, so far as possible, had been ruined by the enemy.

On June 8, the Forty-sixth Division carried out a raid upon so vast a scale that both the results and the losses were greater than in many more serious operations. The whole of the 138th Brigade was concerned in the venture, but the brunt was borne by the 4th Lincolns and 5th Leicesters. On this occasion, use was made upon a large scale of dummy figures, a new device of the British. Some 400 of these, rising and falling by means of wires, seemed to be making a most heroic attack upon an adjacent portion of the German line, and attracted a strong barrage. In the meanwhile, the front trenches were rushed with considerable losses upon both sides. When at last the assailants returned, they brought with them twenty prisoners and a number of machine-guns, and had killed or wounded some hundreds of the enemy, while their own losses came to more than

On June 19, the 138th Brigade, moving in conjunction with the Canadians, took and consolidated some of the trenches opposite them. Unhappily, their position did not seem to be clearly appreciated, as some of our own gas projectors fell in their new trench, almost exterminating a company of the 5th Leicesters. The sad tragedy is only alleviated by so convincing if painful a proof of the powerful nature of these weapons, and their probable effect upon the Germans.

The combined pressure of the Forty-sixth Division and of the Fourth Canadians began now to close in upon Lens. Upon June 25 the 6th South Staffords, with the brave men of the Dominion operating to the south of them, pushed the Germans off Hill 65. Upon June 28 there was a further advance of the 137th and 138th Brigades, which was much facilitated by the fact that the Canadians upon the day before had got up to the village of Leuvette upon the south. A number of casualties were caused by the German snipers after the advance, and among the killed was M. Serge Basset, the eminent French journalist, who had followed the troops up Hill 65.

A successful advance was made by the Forty-sixth Division and by the Canadians upon the evening of June 28, which carried them into the village of Avion and ended in the capture of some hundred prisoners. This operation was undertaken in conjunction with the Fifth Division near Oppy, upon the right of the Canadians. Their advance was also attended with complete success, the 95th and 15th Brigades clearing by a sudden rush more than a mile of German line and killing or taking the occupants. To the north of them both the 4th Canadians and the 46th Midlanders carried the success up the line. The advance was an extraordinary spectacle to the many who looked down upon it from the Vimy heights, for a violent thunderstorm roared with the guns, and a lashing downpour of rain beat into the faces of the Germans. They were tired troops, men of the Eleventh Reserve division, who had already been overlong in the line, and they could be seen rushing wildly to the rear before the stormers were clear of their own trenches. An unfired and brand-new machine-gun was found which had been abandoned by its demoralised crew. The flooded fields impeded the advance of the Canadians, but the resistance of the enemy had little to do with the limits of the movement.

Upon June 30 the 6th North Staffords and 7th Sherwood Foresters made a fresh advance and gained their objectives, though with some loss, especially in the case of the latter battalion. This operation was preparatory to a considerable attack upon July 1. This was carried out upon a three-brigade front, the order being 139th, 137th, 138th from the north. The 139th were in close touch with the Sixth Division, who had lent two battalions of the 71st Brigade to strengthen the assailants. The objective was from the Souchez River in the south, through Aconite and Aloof Trenches, to the junction point of the Sixth Division, north-west of Lens. The day’s fighting was a long and varied one, some ground and prisoners being gained, though the full objective was not attained. The dice are still badly loaded against the attack save when the guns throw their full weight into the game. The Lincoln and Leicester Brigade in the south had the suburb of Cité du Moulin as their objective, and the 4th Lincolns next to the Canadians got well up; but the 5th Lincolns on their left were held up by wire and machine-guns. Through the gallantry of Sergeant Leadbeater one party penetrated into the suburb and made a lodgment in outlying houses, although their flank was entirely in the air. As the day wore on, the line of the 138th Brigade was driven in several times by the heavy and accurate shell-fire, but was each time reoccupied by the enduring troops, who were relieved in the morning by the 4th and 5th Leicesters, who spread their posts over a considerable area. One of these small posts, commanded by Lieutenant Bowell, was forgotten, and held on without relief, food, or water until July 5, when finding himself in danger of being surrounded this young officer effected a clever withdrawal — a performance for which he received the D.S.O.

Whilst the 138th Brigade had established itself in the fringes of Cité du Moulin, the Stafford men upon their left (137th Brigade) had captured Aconite Trench and also got among the houses. A number of the enemy were taken in the cellars, or shot down as they escaped from them, the Lewis guns doing admirable work. About one o’clock, however, a strong attack drove the Stafford men back as far as Ague Trench. The support companies at once advanced, led by Major Graham of the 5th North St affords, who was either killed or taken during the attack, which made no progress in face of the strong masses of German infantry. The result of this failure was that the remnants of two companies of the 5th North Staffords, who had been left behind in Aconite Trench, were cut off and surrounded, all who were not killed being taken. In spite of this untoward result, the fighting on the part of the battalions engaged had been most spirited, and the conflict, after the fall of most of the officers and sergeants, had been carried on with great ardour and intelligence by the junior non-commissioned officers.

On the left, the Sherwood Forest Brigade (strengthened by the 2nd Regular battalion of their own regiment) advanced upon the Lens-Lievin road and the network of trenches in front of them. It was all ideal ground for defence, with houses, slag-heaps, railway embankments, and everything which the Germans could desire or the British abhor. The brigade had advanced upon a three-battalion front, but as the zero hour was before dawn, and the ground was unknown to the Regular battalion upon the right, the result was loss of direction and confusion. Separated parties engaged Germans in isolated houses, and some very desperate fighting ensued. In the course of one of these minor sieges, Captain Chidlow-Roberts is said to have shot fifteen of the defenders, but occasionally it was the attackers who were overpowered by the number and valour of the enemy. The Germans tried to drive back the British line by a series of counter-attacks from the Lens-Bethune road, but these were brought to a halt during the morning, though later in the afternoon parties of German bombers broke through the scattered line, which presented numerous gaps. The losses of the Sherwood Forester Brigade were considerable, and included 5 officers and 186 men, whose fate was never cleared up. Most of these were casualties, but some remained in the hands of the enemy. The total casualties of the division in this action came to 50 officers and about 1000 men.

This hard-fought action concluded the services of the North Midland Division in this portion of the front. It had been in the line for ten weeks, and under constant fire for the greater part of that time. The strength of the battalions had been so reduced by constant losses, that none of them could muster more than 300 men. Upon July 2 the Forty-sixth Division handed over their line to the Second Canadians and retired for a well-earned rest. Save for two very fruitful raids in the Hulluch district in the late autumn, this Division was not engaged again in 1917.

The Germans had strengthened the defence of Lens by flooding the flats to the south of the town, submerging the Cité St. Augustin, so that the Fourth Canadians on the right of the Forty-sixth Division could not push northwards, but they had advanced with steady perseverance along the south bank of the Souchez, and got forward, first to La Coulotte and then as far as the village of Avion, which was occupied by them upon June 28 — a date which marked a general move forward on a front of