Democracy of Sound (20 page)

Read Democracy of Sound Online

Authors: Alex Sayf Cummings

Tags: #Music, #Recording & Reproduction, #History, #Social History

Johnston valued his relationship with Dylan, Cohen, and Cash and was unlikely to endanger it by leaking music they chose not to publish. However, other producers could not have been so conscientious if the flood of unreleased music by major stars is any indication. Sound engineers and other staff could be tempted to take acetates and tapes out of the studio, whether to “liberate” the music, make some extra money, or stick it to their employer. A 1952 essay by Hot Record Society alum Charles Edward Smith suggests that this practice had a long history: “The collector must rely upon the never quite infallible ear of the critic, to tell him whether this is the first master, the second master, or the acetate test that the office boy filched from the wastepaper basket.”

9

Even without the assistance of a sound engineer, getting music out of the concert hall was easier than before. As early as 1901, Lionel Mapleson was lugging his wax cylinder recorder all over the Metropolitan Opera House, searching for a place where he could keep the cumbersome machine out of view. Not everything had changed by the 1960s; a cartoon in

Stereo Review

shows a woman in a fur coat trying to enter an opera house with a microphone sticking out of her extravagant hat. However, those with the money or ingenuity could do a much better job of concealing their equipment. They snuck into concerts, especially as tape recorders became more compact, flexible and effective. The most advanced organizations would send an agent into a concert with a microphone that transmitted to a van, where tape was rolling a quarter of a mile away. Small-scale success allowed ambitious bootleggers to invest in better equipment. One could start with a simple tape recorder costing $40 and work up to a $100,000 stereo system. “Music-trade publications and underground newspapers carry ads for the machines,”

Time

observed in 1971, “and many an Aquarian-Ager has been able to convert his basement into a tape factory.”

10

Michael “Dub” Taylor used his profits from a Bob Dylan bootleg to move up from pilfering studio outtakes to producing high-quality concert recordings; he was spotted in 1971 at a Faces concert with a $3,000 microphone hidden in a suitcase.

11

Law enforcement began worrying about the penetration of bootleggers into concerts before there were even laws to enforce. Congress would extend copyright to sound recordings in 1971, and North Carolina did not pass its own

antipiracy law until 1975, yet high school students in Charlotte reported police monitoring at a Jimi Hendrix concert in 1969. An officer asked one attendee if his movie camera was a tape recorder—apparently, a concert video was acceptable, but a sound-only recording was not. The policeman then asked his friend about a suspicious case:

Cop: What’s in that case under your chair?

Friend: A poloroid [

sic

] camera.

Cop: Do you have a tape recorder?

Friend: No.

Cop: Open up the case.

Friend: Do you have a search warrant?

Cop: Open it up.

Friend: I don’t believe I have to without a search warrant.

Cop: (grabbing him by the arm) Step outside.

Friend: (by this time a uniformed pig appeared) Am I not entitled to a search warrant by the Constitution?

Cops: Step outside son.

12

That summer, the first major rock bootleg began to circulate in Los Angeles: a passel of tunes by Bob Dylan, recorded in hotel rooms, radio and record studios, and, most famously, the basement of Dylan’s home in Woodstock, New York. The bulk of these basement tapes consisted of covers and new folk songs performed with members of the Band during the period between the singer’s motorcycle accident in 1966 and his return with

John Wesley Harding

in late 1967.

13

Word leaked of an unreleased set of Dylan songs, written and performed in the fashion of his early 1960s work, while many fans had greeted his just-released country album,

Nashville Skyline

, with dismay. Reviewers in the

Berkeley Barb

and other left-leaning independent magazines expressed disgust at Dylan’s innocuous musings on “country pie” while the Vietnam War dragged on and student rebellion raged. Even as the Top 40 format imposed uniformity on many radio stations and DJs, the emergence of “free form” radio on the West Coast allowed hosts to air new, unreleased, and soon-to-be released music at will, culled from review tapes sent out by labels to critics or recordings ferreted out of local recording studios.

14

The album of Dylan’s “basement tapes,”

Rolling Stone

reported in 1969, “was collected, pressed and currently is being marketed by two young Los Angeles residents both of whom have long hair, a moderate case of the shakes (prompted by paranoia) and an amusing story to tell.” The young men went by the names of Patrick and Vladimir, until both interviewer and interviewee found the latter too difficult to spell and opted instead for Merlin. By hook or crook, the two had obtained tapes of unreleased Dylan songs, including recordings made in hotel rooms, a few off-the-cuff “rap sessions,” and a live TV performance with Johnny Cash. Lacking their own vehicle, they had to borrow cars to deliver the records to the Psychedelic Supermarket and other local retailers. Although they struggled to keep their names and addresses secret, many people had already approached them with other “secret tapes” for future release. “He’s got all these songs nobody’s ever heard,” Patrick said of Dylan. “We thought we’d take it on ourselves to make this music available.” Jerry Hopkins ended the interview with this question: “Do you know what will happen if you get away with it? Why, if John Mayall or anybody opens at the Whisky tonight, there’ll be a live recording of it on the stands by the middle of next week.”

15

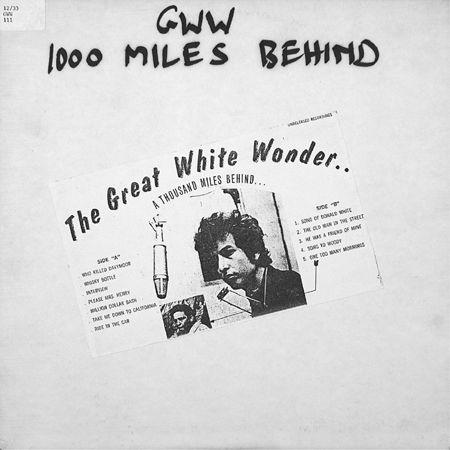

Figure 4.1

An unknown label released this bootleg record, one of many different compilations of Bob Dylan’s “basement tapes” to circulate under the title the

Great White Wonder

, beginning in 1969. It has the same blank aesthetic as many of the

Great White Wonder

records, with a paper label listing the album title and the song tracks glued to the front of the sleeve.

Source:

Courtesy of Music Library and Sound Recordings Archive, Bowling Green State University.

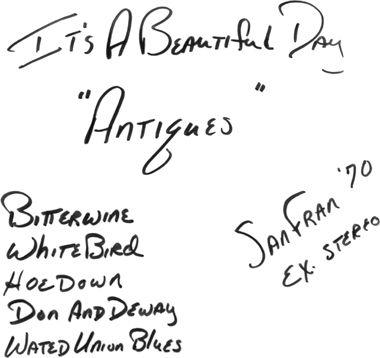

Figure 4.2

The cover of this 1970 bootleg of the San Francisco band It’s a Beautiful Day features only text handwritten with a black marker—prefiguring the way listeners labeled “burnt” CDs later in the twentieth century.

Source:

Courtesy of Music Library and Sound Recordings Archive, Bowling Green State University.

These earliest rock bootlegs were minimalist by default, with plain white covers that gave little or no indication of what was contained inside. When a woman from Brooklyn saw the Dylan album and expressed interest in hyping it back in New York, she told the boys it needed a name. Based on its presentation, she suggested

Great White Wonder

. Subsequently, Patrick and Merlin stamped each release with the letters “GWW.” According to

Rolling Stone

, “Some [stores] objected to the simple packaging—a white double sleeve with ‘Great White Wonder’ rubber stamped in the upper righthand corner—they said, while others indicated they were afraid of how Columbia might react.”

16

Many other versions of these recordings followed, as entrepreneurs imitated the style of the original and either tried to improve the sound quality of the material or offered a slightly different assortment of live recordings and demos.

The blank design of the early

Wonder

s recalled what became known as the Beatles’

White Album

, released the year before. Designed by pop artist Richard Hamilton, the 1968 record originally featured a plain white cover, the lack of adornment mirroring its simple title:

The Beatles

. In other words, it was just the

band, with no fanfare or addenda. (It was also the first album they released on their own label, Apple Corps.) While a blank album cover might be expected to stand out on the record shelves—Hamilton wanted its militant abstraction to resemble “the most esoteric art publications”—Apple still added the stamp “The Beatles” on the cover to ensure that fans knew what the record was.

17

Great White Wonder

stood in contrast with standard music industry product much as the

White Album

did, as a plain container filled with an unalloyed volume of the artist’s work. Packaging design is an aspect of marketing, a central piece of the campaign to tantalize the public into purchasing any musical product, and thus represents a portion of the investment in production and promotion that record companies accused pirates of appropriating. The earliest bootlegs, however, exploited this investment only indirectly; pirates may have benefited from the attention already generated by the promotional machine, but they did not copy the graphic design of the product. In the case of

Wonder

, they were not even copying an actual major-label release. Alan Bayley of GRT Corp., which manufactured tape versions of albums for major labels, urged the music industry to adopt an industry-wide trademark to distinguish legitimate recordings, but

Business Week

observed that in most cases the difference was already evident: “Authentic tapes are nicely packaged with full-color illustrations whereas bootleg tapes generally have a plain printed label listing the performers and songs and no maker’s name or address.”

18

Aesthetics aside, the plainness served more practical purposes. The two young men who first published

Great White Wonder

lacked the resources to create a more elaborate production, even with the funds they scared up from a local businessman known only as “the Greek.” Further, Patrick’s desire to get the basement tapes into the hands of frustrated fans required forgoing much attention to detail in terms of presentation. Plain white packaging might have prevented police or other authorities from recognizing a record as the work of an artist on a major label, at least until the design became well known enough for the public to associate it with bootleg music.

If nothing else, leaving the sleeve blank could keep anyone from tracing the record to a particular bootlegger—unless, of course, he had the album manufactured at Columbia Records’ own pressing plant in Los Angeles. A young man named Michael O made this mistake, issuing his own edition of

Great White Wonder

after being displeased with the original release. His was also packaged in a white sleeve, distinguished only by one low-budget touch—a drawing of a flower by his girlfriend on each of the 200 releases, which led to its being dubbed

Flower

by retailers. Michael found his mother at home one afternoon, fuming because a Columbia rep had come by and insisted that the boy buy back whatever records he had sold and turn them over to Columbia. Another entrepreneur in the area took a stab at perfecting the basement tapes, releasing a ten-track record

in another blank sleeve. Like

Flower

, it also got its name from retailers, who saw the letters TT inscribed on the disc label and called it

Troubled Troubadour

.

19

As the summer and fall of 1969 wore on, multiple versions of the basement tapes circulated. Retailers expressed astonishment that young people would buy up any bootleg available, with no sure knowledge of what it contained or whether it duplicated another record they owned. Recorded music came unmoored from any kind of fixed identity; fans could no longer assume that a recording was one of a definite sequence of releases by a particular artist in a label’s catalog, recorded and packaged for sale at a definite moment in time, nor could they be sure whether the sounds had appeared elsewhere in slightly different form. Sound became free-floating and promiscuous, like the motley mix of recordings by any artist that one might find on a spindle of “burnt” CDs or a computer hard drive in the twenty-first century. The music’s provenance, its release date, even the identity of the performer was far less certain than those of a glossy, well-designed LP released by a legitimate label. The tireless effort of record companies to build the stardom and image of their performers crumbled in the face of widespread duplication.