Democracy of Sound (24 page)

Read Democracy of Sound Online

Authors: Alex Sayf Cummings

Tags: #Music, #Recording & Reproduction, #History, #Social History

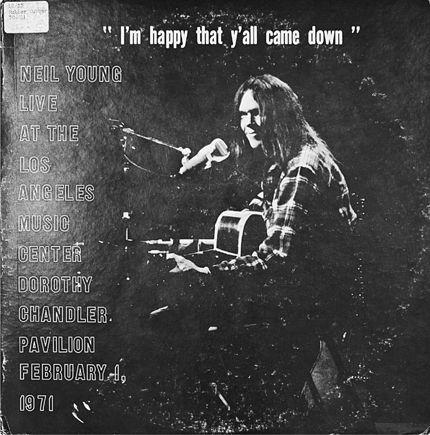

In California, Tom worked in sales and recording, capturing performances by artists such as Elton John, James Taylor, and Neil Young.

84

Rubber Dubber made sure to snap up tickets for the best seats in the house as soon as they were

available. Chuck Kane would carry a high quality reel-to-reel tape recorder to the concert in his backpack, while Tom had to maneuver with a long microphone stuck in his pants. Although it looked awkward, no one ever bothered him about it. “One person would limp in with a shotgun mic down one leg,” Tom said. “That was never noticed because of all the returning Vietnam vets with injuries.” Although the sound quality was not excellent, the recordings captured the feel of the live performance. The Rubber Dubber gang saw this product as having more value than the pirated tape of an album that was already a hit. “We did not put ourselves in the same category as them,” Tom said. “We were selling something that was totally new and captured from the ‘air.’” At the time, he believed that they were giving the fans something they wanted and paying the artists for their work; although he began to suspect that what they were doing was illegal, everybody seemed to win.

Like many things with Rubber Dubber, the truth differed from the image. According to Heylin, Dubber’s leader was the scion of a Dallas crime family who wandered away from the family business.

85

The evidence suggests that he did not stray very far. Terry Conklin, a Laguna Beach drug dealer, had ponied up funds to get the organization going, and some participants pulled in additional cash from credit card scams. Of course, as Tom said, the group’s leaders could afford to be “very generous, as they never paid for anything.” When Ed Ward asked Rubber Dubber’s leader, “How do you expect to make money?” he responded that they had no need for profits. The group divided up its proceeds equally, and looked after the rent, health insurance, and Social Security of its employees.

86

However, the reality was not so communist; the sales staff, for example, worked on commission. Tom insists that the workers never got a share of the profits, nor did the artists ever receive a dime. “It didn’t take long to see through those guys,” he says. “They were only in it for personal gain.”

87

By late 1971 time was already running out. A bill providing federal copyright protection for sound recordings passed Congress in August, and Rubber Dubber rushed to sell off as much of its stock as possible.

88

After its Crosby, Stills and Nash bootleg hit the shelves, David Crosby hired detectives to monitor the group, although the investigation turned into a farce. Several gumshoes followed a trail all the way to a school for the deaf in Texas, which Rubber Dubber had led them to believe was a bootleg factory. Meanwhile, in Kansas, another team of detectives banged on the door of a man they were sure was the group’s leader at four in the morning. “After he’d listened to them trying to serve the subpoena on him, he ripped it into shreds and threw them in jail for disturbing the peace,” Ward wrote. “He was the county sheriff.”

89

A more serious encounter soon followed. US Marshalls descended on the Dubber headquarters, deep in the warehouse district of East Los Angeles. Kane had to keep the lawmen occupied in the office while Tom and the other employees removed all the contraband from

the warehouse and drove away. “It fell apart after the raid and never really recovered,” Tom said. “By that time, the idealists like me had already moved on.”

90

Many of the bootleggers got out of the business after the new copyright law went into effect in February 1972. For example, Rubber Dubber’s leader quit after a few close brushes with the law, although he landed in jail on a murder charge years later. Tom Brown went to Oregon to seek spiritual enlightenment shortly after the US Marshals showed up. Jan Bohusch turned on his former partner and testified about their activities at a public hearing in New York in 1974. Some, like Bohusch’s partner, kept on copying, in part because the 1971 law only banned the reproduction of recordings copyrighted after the statute went into effect. Some used the same tactics as Boris Rose and the Bronx baker, who put out each record on a different label to cover their tracks. For example, one bootleg group in the mid-1970s issued each of its records under names like Hen, Led, and Steel Records.

91

After the law changed and the fervor of the late 1960s faded, rock bootlegging reverted to much the same form as the jazz and classical piracy before it, continuing to provide live performances and other rarities to a devoted fan base. No longer making splashy statements about changing the system, these bootleggers were, in Denisoff and McCaghy’s terms, essentially collectors’ pirates. A countercultural tendency did persist, perceptible in the role of bootlegs in spreading the word about punk rock and hip-hop. Throughout the 1970s, record companies, musicians, and politicians struggled to squelch the growth of unauthorized reproduction through increasingly punitive copyright reform and new kinds of law enforcement; during the same period, piracy endured and evolved in response to legal suppression at the state, federal, and ultimately, international levels.

|| 5 ||

The Criminalization of Piracy

Even as war, riots, and rock and roll shook the United States in the 1960s, Congress continued to fiddle with copyright reform. When

Great White Wonder

appeared in 1969, lawmakers were considering yet another proposal to give the record industry what it had wanted for sixty years: a separate copyright for sound recordings. The numerous legislative false starts of the era forced labels to look elsewhere for help in dealing with the surge of music piracy, first with renewed litigation on the grounds of unfair competition, and then by lobbying state governments to pass their own antipiracy laws. Lawsuits proved costly and ineffective, as pirates found it easy to dodge injunctions and other penalties, often by leaving one state and setting up shop across the border. And state laws raised constitutional questions about whether the states were creating an unlimited quasi-copyright, thus intruding on the federal government’s turf.

California’s 1968 statute, one of the first and one of the strictest, was challenged at the state and federal level, leaving the debate open until the Supreme Court’s 1973

Goldstein v. California

decision.

1

By then, Congress had already responded to the bootleg boom by extending copyright to sound recordings. When that reform failed to quash piracy, lawmakers strengthened fines and enforcement and ultimately passed a measure in 1976 that changed the terms of copyright for decades to come.

Stirrings of Reform, 1955–1964

Why did Congress decide to take up the issue of copyright again in 1955? Dante Bollettino and other bootleggers had made headlines in the early 1950s by copying rare and out-of-print jazz recordings. Record companies used these incidents to remind lawmakers of the shortcomings of the last major copyright revision, passed in 1909. Indeed, the 1920s and 1930s saw lawmakers attempt to bring US law in line with the Berne Convention, an international agreement signed in

1886, but each effort failed because of discord among publishers, record companies, broadcasters, and other interests. Congress abandoned the revision project in 1940 to handle the more pressing concerns of war.

2

With the return of peace, politicians turned their attention to copyright once more and attempted to assess the role of the media and culture industries in the booming economy. Economic growth meant that consumers had money to spend on nonessential goods, whether a bootleg of New York’s Metropolitan Opera or an old Jelly Roll Morton recording. Pirates could take advantage of consumers’ greater disposable income and the youth market by satisfying a demand unmet by the major record companies. Television and radio provided more material for bootleggers to copy and sell, and advances in recording technology made it easier to do so.

The first signs of friction over unauthorized reproduction emerged soon after World War II. The entertainment capital of Los Angeles passed the first criminal law forbidding piracy in 1948, and California would be one of the first states (second only to New York) to approve a similar statute in 1968.

3

Music labels formed the Recording Industry Association of America in 1952 to protect their interests, which consisted largely of maintaining the compulsory license system (which permitted them to record songs by paying a low fixed royalty) and stopping the illicit reproduction of records. Never known for its celerity, Congress began to reconsider the issue in 1955, funding a series of studies on copyright and related industries; a stopgap measure to provide copyright for sound recordings would arrive sixteen years later, and the long-awaited comprehensive revision came only in 1976.

Congress passed the first Copyright Act in 1790, and major revisions ensued about every forty years—in 1831, 1870, and 1909. Judging by this pattern, an overhaul was due by the 1950s. Reporting to Congress, economist William Blaisdell calculated that various industries had generated $6.1 billion from the use and sale of their copyrighted products, out of a national income of $299.7 billion. The aggregate of radio stations, newspapers, record stores, and related businesses earned more than banks, mines, or utilities, and slightly less than the auto industry, even in the 1950s heyday of General Motors.

4

Blaisdell’s study showed Congress that various media represented a sizable share of the nation’s economic output, but the qualitative changes were at least as significant as the quantitative ones. Radio and television broadcasting did not even exist when the 1909 act was passed, and the film and recording industries were then only beginning to take shape.

5

In 1961 the Register of Copyrights, Abraham Kaminstein, made a series of recommendations that addressed looming controversies in music and publishing, among other industries. He proposed ending the compulsory license for musical compositions, which would allow songwriters to license their work

selectively, like any other copyrighted item. Publishers were eager to see the existing system terminated, since they hoped to negotiate higher prices for the use of their songs than the flat rate fixed by Congress. Record companies, on the other hand, wanted to be able to record any song without negotiating deals with individual composers or publishers.

6

Kaminstein also hinted at the brewing conflict over “new techniques for reproducing printed matter,” such as the Xerox machine, an increasingly vital tool in labs, libraries, and offices throughout the country. A long and bitter conflict over “fair use” would play out during the 1960s and 1970s, pitting academic publishers against the National Institutes of Health, whose libraries regularly photocopied articles from science journals in large numbers for researchers throughout the country.

7

Before the mêlée broke out, the Register recommended that a library be restricted to making a single photocopy of an item in its collection, with specific guidelines to be worked out later. As for music piracy, Kaminstein was cautious: “This report … favors the principle of protecting sound recordings against unauthorized duplication, but makes no specific proposals pending further study.”

8

Indeed, over fifty years of experience failed to yield a solid answer about what to do with recordings. There still was no consensus about whether a mechanical reproduction of music was a “writing” apart from the song on which it was based, or, if it was, then who the writer was. The Constitution allows an author to benefit financially from his writings, but the first Congress included only books, maps, and charts in this category, to which legislators added (written) music in 1831 and photographs in 1865.

9

As the Supreme Court noted in its controversial 1908

White-Smith

decision, Americans had only attributed copyright to works that were visually perceptible. One could understand letters, musical notes, and images, whether printed, painted, or photographed with the naked eye. To Justice William Day, the grooves on a phonograph disc and the holes in a piano roll were not the same thing. They were more like the gears in a clock than the words in a book. Machines could be patented on the basis of what they did, not what they meant, and patents had to reach a higher standard of novelty than the standard of originality for copyrighting an expression.

10

Congress could have decided to take the unprecedented step of recognizing a mechanical application of expression under copyright, but, as we saw in

chapter 1

, lawmakers chose not to recognize the recorded performance as a copyrightable expression, separate from the song itself.