Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (16 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

4.38Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

That was probably the happiest year of Abu Muslim’s life, the year his life’s work came to fruition at last! Perhaps he really thought that toppling the Umayyads would restore the quest for the lost community. Disillusionment soon set in, however. For one thing, the puppet did not, it

turned out, consider himself a puppet. Over the years, Abbas had built a real base within the movement that had chosen him as its figurehead, and now that Abu Muslim had done the donkey work, he said thank you very much and took the throne.

turned out, consider himself a puppet. Over the years, Abbas had built a real base within the movement that had chosen him as its figurehead, and now that Abu Muslim had done the donkey work, he said thank you very much and took the throne.

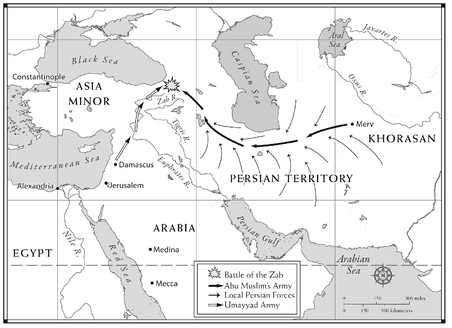

ABU MUSLIM AND THE ABBASID REVOLUTION

The new khalifa remembered that Mu’awiya had consolidated his power by slipping a velvet glove over his iron fist and winning over former foes with courtesy and charm. Accordingly, the new ruler invited leading members of the Umayyad clan to break bread with him, just to show that there were no hard feelings.

Well, I shouldn’t say “break bread.” That makes it sound like he was going to serve his guests a simple meal of barley bread and soup, such as the Prophet might have shared with Omar. That sort of thing was now out of fashion. No, the Umayyad survivors found themselves lolling on cushions while servants pranced in with lovely trays piled high with gourmet delicacies. The laughter rang out, the conversation turned spirited, and a sense of camaraderie swelled. Just as everyone was getting ready to tie into the meal, however, the waiters threw off their robes to reveal armor underneath. T

hey weren’t waiters, it turned out, but executioners. The Umayyads jumped to

their feet, but too late: the doors had all been locked. The soldiers proceeded to club the Umayyads to death. From that time on, Abbas went by a new title, al-Saffah, which means “the slaughterer.” Apparently, he took some pride in what he had done.

hey weren’t waiters, it turned out, but executioners. The Umayyads jumped to

their feet, but too late: the doors had all been locked. The soldiers proceeded to club the Umayyads to death. From that time on, Abbas went by a new title, al-Saffah, which means “the slaughterer.” Apparently, he took some pride in what he had done.

Little good it did him, however, for he soon died of smallpox and his brother al-Mansur took over. Mansur had to tussle with rivals a bit, but Abu Muslim stepped in and secured the throne for him, then returned to Khorasan. Abu Muslim made no bid for the khalifate on his own behalf, even though he had the military power to take what he wanted. He seemed to accept the legitimacy of Abbasid rule. Perhaps he really was a principled idealist.

And yet there was something Mansur just didn’t like about this man, Abu Muslim. Well, perhaps it was one particular thing: Abu Muslim was popular. All right, two things: he was popular, and he had soldiers of his own. A ruler can never trust a popular man with soldiers of his own. One day, Mansur invited Abu Muslim to come visit him and share a hearty meal. What happened next illustrates the maxim that when an Abbasid ruler invites you to dinner, you should arrange to be busy that night. The men got together at a pleasant riverside campsite and Mansur spent the first day lavi

shly thanking Abu Muslim for all his selfless services; the next night he had his bodyguards cut Abu Muslim’s throat and dump his body in the river.

shly thanking Abu Muslim for all his selfless services; the next night he had his bodyguards cut Abu Muslim’s throat and dump his body in the river.

Thus began the second dynasty of the Muslim khalifate.

Abbasid propagandists got busy creating a narrative about the meaning of this transition. They called it a revolutionary new direction for the Umma. Everything would be different now, they said. In fact, everything remained pretty much the same, only more so, both for better and for worse.

The Umayyads had steeped themselves in pomp and luxury, but the Abbasids made them seem by comparison like rugged yeomen living the simple life. Under the Umayyads, the Muslim realm had grown quite prosperous. Well, under the Abbasids, the economy virtually exploded with vigor. And like the Umayyads, the Abbasids were secular rulers who used spies, police power, and professional armies to maintain their grip.

Since the Abbasids had risen to power on a surge of Shi’ite discontent, you might suppose that in this regard at least they would have differ

ed from the Umayyads, but in this supposition you would be dead wrong. The Abbasids quickly embraced the orthodox approach to Islam, probably because the orthodox religious establishment, all those scholars, had secured so much social power in Islam that embracing their doctrines was the politic thing to do. Indeed, it was only in Abbasid times (as we shall see in the next chapter) that the mainstream approach to Islam acquired the label Sunnism, since only now did it congeal into a distinct sect with a name of its own.

ed from the Umayyads, but in this supposition you would be dead wrong. The Abbasids quickly embraced the orthodox approach to Islam, probably because the orthodox religious establishment, all those scholars, had secured so much social power in Islam that embracing their doctrines was the politic thing to do. Indeed, it was only in Abbasid times (as we shall see in the next chapter) that the mainstream approach to Islam acquired the label Sunnism, since only now did it congeal into a distinct sect with a name of its own.

In the first days of the Abbasid takeover, many naïve Shi’i thought that Saffah and his family were going to put the recognized Shi’ite imam on the throne, thereby inaugurating the millennial peace predicted in Hashimite propaganda. Instead, the hunt for Alids intensified. In fact, when the third khalifa of this dynasty died, according to one of his maids, his successor found a secret room in his palace, which led to an underground vault where he had collected the corpses of all the Alids he had captured and killed. (They weren’t necessarily Fatima’s descendants, since Ali had other wives a

fter Fatima died).

fter Fatima died).

Yet the Abbasids also maximized everything that was good about Umayyad rule. The Umayyads had presided over a flowering of prosperity, art, thought, culture, and civilization. All this splendor and dynamism accelerated to a crescendo during the Abbasid dynasty, making the first two centuries or so of their rule the one that Western history (and many contemporary Muslims) remember as the Golden Age of Islam.

One of Mansur’s first moves, for example, was to build himself a brand new capital, a city called Baghdad, completed in 143 AH (765 CE). The city he built has survived into the present day, though it has been destroyed and rebuilt several times over the centuries, and is in the process of being destroyed again.

Mansur toured his territories for several years before he found the perfect site for his city: a place between the Tigris and Euphrates where the rivers came so close together that a city could be stretched from the banks of one to the banks of the other. Smack dab in the middle of this space, Mansur planted a perfectly circular ring of wall, one mile in circumference, 98 feet high, and 145 feet thick at the base. The “city” within this huge doughnut was really just a single enormous palace complex, the new nerve center for the world’s biggest empire.

1

1

It took five years to build the Round City. Some one hundred thousand designers, craftspeople, and laborers worked on it. These workers lived all around the city they were building, so their homes formed another, less orderly ring of city around the splendid core. And of course shopkeepers and service workers flocked in to make a living selling goods and services to the people working on the Round City, which added yet another urban penumbra around the disorderly ring that surrounded that perfect circular core.

Within twenty years, Baghdad was the biggest city in the world and possibly the biggest city that had ever been: it was the first city whose population topped a million.

2

Baghdad spread beyond the rivers, so that the Tigris and Euphrates actually flowed through Baghdad, rather than beside it. The waters were diverted through a network of canals that let boats serve as the city’s buses, making it a bit like Venice, except that bridges and lanes let people navigate the city on foot or on horseback too.

2

Baghdad spread beyond the rivers, so that the Tigris and Euphrates actually flowed through Baghdad, rather than beside it. The waters were diverted through a network of canals that let boats serve as the city’s buses, making it a bit like Venice, except that bridges and lanes let people navigate the city on foot or on horseback too.

Baghdad might well have been the world’s busiest city as well as its biggest. Two great rivers opening onto the Indian Ocean gave it tremendous port facilities, plus it was easily accessible to land traffic from every side, so ships and caravans flowed in and out every day, bringing goods and traders from every part of the known world—China, India, Africa, Spain. . . .

Commerce was regulated by the state. Every nationality had its own neighborhood, and so did every kind of business. On one street you might find cloth merchants, on another soap dealers, on another the flower market, on yet another the fruit shops. The Street of Stationers featured over a hundred shops selling paper, a new invention recently acquired from China (whom the Abbasids met and defeated in 751 CE, in the area that is now Kazakhstan). Goldsmiths, tinsmiths, and blacksmiths; armorers and stables; money changers, straw merchants, bridge builders, and cobblers, all could be f

ound hawking their wares in their designated quarters of mighty Baghdad. There was even a neighborhood for open-air stalls and shops selling miscellaneous goods. Ya’qubi, an Arab geographer of the time, claimed that this city had six thousand streets and alleys, thirty thousand mosques, and ten thousand bathhouses.

ound hawking their wares in their designated quarters of mighty Baghdad. There was even a neighborhood for open-air stalls and shops selling miscellaneous goods. Ya’qubi, an Arab geographer of the time, claimed that this city had six thousand streets and alleys, thirty thousand mosques, and ten thousand bathhouses.

This was the city of turrets and tiles glamorized in the

Arabian Nights,

a collection of folk stories transformed into literature during the later days of the Abbasid dynasty. Stories such as the one about Aladdin and

his magic lamp hark back to the reign of the fourth and most famous Abbasid khalifa, Haroun al-Rashid, portrayed as the apogee of splendor and justice. Legends about Haroun al-Rashid characterize him as a benevolent monarch so interested in the welfare of his people that he often went among them disguised as an ordinary man, so that he might learn first-hand of their troubles and take measures to help them. In reality, I’m guessing, it was the khalifa’s spies who went among the people disguised as ordinary beggars, not so much looking for troubles to right as malconten

ts to neutralize.

Arabian Nights,

a collection of folk stories transformed into literature during the later days of the Abbasid dynasty. Stories such as the one about Aladdin and

his magic lamp hark back to the reign of the fourth and most famous Abbasid khalifa, Haroun al-Rashid, portrayed as the apogee of splendor and justice. Legends about Haroun al-Rashid characterize him as a benevolent monarch so interested in the welfare of his people that he often went among them disguised as an ordinary man, so that he might learn first-hand of their troubles and take measures to help them. In reality, I’m guessing, it was the khalifa’s spies who went among the people disguised as ordinary beggars, not so much looking for troubles to right as malconten

ts to neutralize.

Even more than in Umayyad times, the khalifa became a near mythic figure, whom even the wealthiest and most important people had little chance of ever seeing, much less petitioning. The Abbasid khalifas ruled through intermediaries, and they insulated themselves from everyday reality with elaborate court rituals borrowed from Byzantine and Sassanid traditions. So, yes, Islam conquered all the territories ruled by the Sassanids and much that had once been ruled by the Byzantines, but in the end the ghosts of those supplanted empires infiltrated and altered Islam.

7

Scholars, Philosophers, and Sufis

10-505 AH

632-1111 CE

632-1111 CE

S

O FAR I HAVE been recounting political events at the highest levels as Muslim civilization evolved into the civilization of the middle world. Big stories were unfolding, however, below that highest level, and none was bigger than the development of Muslim doctrine, and the social class it generated, along with the opposing and alternative ideas it engendered.

O FAR I HAVE been recounting political events at the highest levels as Muslim civilization evolved into the civilization of the middle world. Big stories were unfolding, however, below that highest level, and none was bigger than the development of Muslim doctrine, and the social class it generated, along with the opposing and alternative ideas it engendered.

Looking back, it’s easy to suppose that Mohammed left his followers exact instructions for how to live and worship, complete in every detail. How complete they were, however, is difficult to gauge. What’s pretty certain is that, in his lifetime, Mohammed established the primacy of five broad duties, now called the five pillars of Islam:

shahadah

, to attest that there is only one God and Mohammed is his

messenger;

salaat

(or

namaz

)

,

to perform a certain prayer ritual five times every

day;

zakat,

to give a certain percentage of one’s wealth to the poor each year;

sawm

(or

roza),

to fast from dawn to dusk during the month of Ramadan

each year; and

hajj,

to make a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in a lifetime, if possible.

, to attest that there is only one God and Mohammed is his

messenger;

salaat

(or

namaz

)

,

to perform a certain prayer ritual five times every

day;

zakat,

to give a certain percentage of one’s wealth to the poor each year;

sawm

(or

roza),

to fast from dawn to dusk during the month of Ramadan

each year; and

hajj,

to make a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in a lifetime, if possible.

Notice both the simplicity and “externalness” of this program. Only one of the five pillars is a belief, a creed, and even that is given in terms of an action: “to attest.” The other four pillars are very specific things to do. Again, Islam is not merely a creed or a set of beliefs: it is a program every bit as concrete as a diet or an exercise regiment. Islam is something one

does.

does.

The five pillars were already part of life in the Muslim community by the time of Mohammed’s death, but so were other rituals and practices, and any of them may have been parsed somewhat differently back then. The fact is, when Mohammed was alive, there was no need to fix the details inflexibly because the living Messenger was right there to answer questions. Not only could people learn from him every day, but through him they might receive fresh instructions at any time.

Indeed, Mohammed did receive revelations continually, not just about general values and ideals but about practical measures to take in response to particular, immediate problems. If an army was approaching the city, God would let Mohammed know if the community should get ready to fight, and if so, how. If Muslims captured prisoners and after the battle was over wondered what to do with them: Kill them? Keep them as slaves? Treat them as members of the family? Set them free? God would tell Mohammed, and he would tell everyone else.

Other books

The Billionaires Mistress by Marie Kelly

A Word Child by Iris Murdoch

Brand New Friend by Mike Gayle

Two Heirs (The Marmoros Trilogy Book 1) by Peter Kenson

Huntress by Taft, J L

Then & Now by Lowe, Kimberly

Novum: Revelation: (Book 4) by Joseph Rhea

The Buenos Aires Marriage Deal by Maggie Cox

The Book of the Sword (Darkest Age) by A. J. Lake

Rebecca Hagan Lee by A Wanted Man