Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (14 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

6.97Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Whatever his shortcomings as a saint, Mu’awiya possessed tremendous political skill. The very qualities that helped him defeat the tormented Ali made him a successful monarch, and his reign institutionalized practices and procedures that would hold an Islamic empire together for centuries.

This is all very ironic because, let us not forget, when Mohammed’s prophetic career began, the Umayyads were a leading clan among the rich elite of Mecca. When Mohammed as Messenger denounced the malefactors of great wealth who ignored the poor and exploited the widows and orphans, the Umayyads were some of the main people he was talking about. When Mohammed still lived in Mecca, the Umayyads outdid each other in harassing his followers. They helped plot the assassination of Mohammed before the Hijra and led some of the forces that tried to extinguish the Umma in its cradle

after the Muslims moved to Medina.

after the Muslims moved to Medina.

But once Islam began to look like a juggernaut, the Umayyads converted, joined the Umma, and climbed to the top of the new society; and here they were again, back among the new elite. Before Islam, they were merely among the elite of a city. Now, they were the top elite of a global empire. I’m sure many among them were scratching their heads, trying to remember what they ever found to dislike in this new faith!

As rulers, the Umayyads possessed some powerful instruments of policy inherited from their predecessors, especially Omar and Othman. Omar had done them a great favor by sanctifying offensive warfare as jihad so long as it was conducted against infidels in the cause of Islam. This definition of jihad enabled the new Muslim rulers to maintain a perpetual state of war on their frontiers, a policy with pronounced benefits.

For one thing, perpetual war drained violence to the edges of the empire and helped keep the interior at peace, reinforcing the theory of a world divided between the realm of peace (Islam) and the realm of war (everything else), which developed in the days of the first khalifas.

Perpetual war on the frontiers helped to reify this concept of war and peace, first of all, by making the narrative

seem

true—the frontier was generally a violent place, while the interior was generally a place of peace and security—and second, by helping to make it actually

be

true. By unifying the Arab tribes against a surrounding Other, this concept of jihad reduced the incessant internecine warfare that marked Arab tribal life before Islam and thus really did help to make the Islamic world a realm of (relative) peace!

seem

true—the frontier was generally a violent place, while the interior was generally a place of peace and security—and second, by helping to make it actually

be

true. By unifying the Arab tribes against a surrounding Other, this concept of jihad reduced the incessant internecine warfare that marked Arab tribal life before Islam and thus really did help to make the Islamic world a realm of (relative) peace!

You can see this dynamic more clearly when you consider who fought the early wars of expansion. It wasn’t so much a case of emperors dispatching armies of professional soldiers to do their bidding according to some master plan. The campaigns were fought by tribal armies who went off to battle more or less when they felt like it, as volunteers for the faith, responding more to the wishes than the orders of the khalifa. If they hadn’t been fighting at the borders to expand the territory under Muslim rule, they might well have been fighting at home to wrest booty from their neighbors.

Perpetual war also worked to confirm Islam’s claim to divine sanction, so long as it kept leading to victory. From the start, astonishing military and political success had functioned as Islam’s core confirming miracle.

Jesus may have healed the blind and raised the dead. Moses may have turned a staff into a snake and led an exodus for which the Red Sea parted. Visible miracles of this ilk proved the divinity or divine sponsorship of those prophets.

Jesus may have healed the blind and raised the dead. Moses may have turned a staff into a snake and led an exodus for which the Red Sea parted. Visible miracles of this ilk proved the divinity or divine sponsorship of those prophets.

Mohammed, however, never really dealt in supernatural miracles such as those. He never solicited followers with displays of power that contradicted the laws of nature. His one supernatural feat, really, was ascending to heaven on a white horse from the city of Jerusalem, and this was not a miracle performed for the multitudes. It happened to him unseen by any public, and he reported it later to his companions. People could believe him or not, as they wished; it didn’t impact his mission, because he wasn’t offering his ascent to heaven as proof that his message was true.

No, Mohammed’s miracle (aside from the Qur’an itself and the persuasive impact it had on so many who heard it) was that Muslims won battles even when outnumbered three to one. This miracle continued to unfold under the first khalifas as Muslim-ruled territory kept expanding at a breathtaking pace, and what could explain success like that except divine intervention?

The miracle continued under the Umayyads. The victories didn’t come as fast, nor as dramatically, but then, the opportunity for truly dramatic victories diminished over time simply because Muslims rarely found themselves as outnumbered as they were at first. The bottom line was that the victories kept coming and the territory kept expanding—it never shrank. So long as this was true, perpetual war continued to confirm the truth of Islam, which fed the fervor that enabled the victories, which confirmed the truth that fed the fervor, which enabled the victories that confirmed the truth . . . and s

o on, round and round.

o on, round and round.

Perpetual war had some tangible benefits too. It brought in revenue. As Muslims told it, some Allah-defying potentate would tax his subjects until his coffers were overflowing; then the Muslims would appear, knock him off his throne, liberate his subjects from his greed, and take his treasures. This made the liberated people happy and the Muslims rich: everybody ended up ahead except the defeated princes.

One-fifth of the plunder was sent back to the capital, and at first all of it was distributed among the Umma, with the neediest taken care of first. But with each khalifa, an increasing percentage went into the public treasury; when the Umayyads took over, they started funneling virtually all revenue into the public treasury and using it to cover the cost

s of government, which included lavish building projects, ambitious public works, and extravagant charitable endowments. Revenue from the perpetual border wars thus enabled the Umayyad government to operate as a positive force in society, lavishing benefits on citizens without raising taxes.

s of government, which included lavish building projects, ambitious public works, and extravagant charitable endowments. Revenue from the perpetual border wars thus enabled the Umayyad government to operate as a positive force in society, lavishing benefits on citizens without raising taxes.

Then there were precedents bequeathed to the Umayyads by Khalifa Othman, who allowed Muslims to spend their money any way they wanted, so long as they followed Islamic strictures. Based on Othman’s rulings, the Umayyads allowed Muslims to purchase land in conquered territory with money borrowed from the treasury. Of course one had to be very well connected to get such loans, even more so than in Othman’s time, and since Islam outlawed usury, these loans were interest-free, which is nice financing if you can get it.

Omar had ordered that Muslim Arab warriors moving into new territories stay in garrisons apart from local populations, in part to avoid trampling on the rights and sensibilities of the locals, in part to keep Muslims from being seduced by pagan pleasures, and in part to keep the minority Muslims from being absorbed into the majority locals. In Umayyad times, these garrisons evolved into fortified Arab cities housing a new landed aristocracy, who owned and profited from vast estates in the surrounding countryside.

Islamic society bore no resemblance to feudal Europe, however, where manors were largely self-sufficient economic units, producing for immediate consumption. The Umayyad Empire hummed with handicrafts, and it was sewn together by intricate trade networks. Wealth milked out of the vast estates didn’t just sit there but proliferated into trade goods that flowed to distant lands and brought other trade goods flowing back. Garrison cities softened into busy commercial entrepôts. The Islamic world was dotted with vigorous cities. It was an urbane world.

Mu’awiya himself, reviled by the devout as a poor show next to such spiritual giants as the Rightly Guided Khalifas, proved himself no slouch as an economic manager and politician. Ruthless but charming, he gained the cooperation of fractious Arab chieftains, mostly with persuasion, using his military and police powers largely to put down revolts and impose law and order, which benefited him but also smoothed the way for civilized life.

Consider the mixture of stick and carrot in this warning to the people of Basra, issued by Mu’awiya’s adopted brother Ziyad, whom he ha

d appointed governor of Basra: “You allow kinship to prevail and put religion second; you excuse and hide your transgressors and tear down the orders which Islam has sanctified for your protection. Take care not to creep about in the night. I will kill every man found on the streets after dark. Take care not to appeal to your kin; I will cut off the tongue of every man who raises that call. . . . I rule with the omnipotence of God and maintain you with God’s wealth. I demand obedience from you and you can demand uprightness from me . . . I will not fail in three things: I will at all times

be there for every man to speak to me. I will always pay your pensions punctually and I will not send you into the field for too long a time or too far away. Do not be carried away by your hatred and anger against me; it would go ill with you. I see many heads rolling. Let each man see that his own head stays upon his shoulders!”

3

d appointed governor of Basra: “You allow kinship to prevail and put religion second; you excuse and hide your transgressors and tear down the orders which Islam has sanctified for your protection. Take care not to creep about in the night. I will kill every man found on the streets after dark. Take care not to appeal to your kin; I will cut off the tongue of every man who raises that call. . . . I rule with the omnipotence of God and maintain you with God’s wealth. I demand obedience from you and you can demand uprightness from me . . . I will not fail in three things: I will at all times

be there for every man to speak to me. I will always pay your pensions punctually and I will not send you into the field for too long a time or too far away. Do not be carried away by your hatred and anger against me; it would go ill with you. I see many heads rolling. Let each man see that his own head stays upon his shoulders!”

3

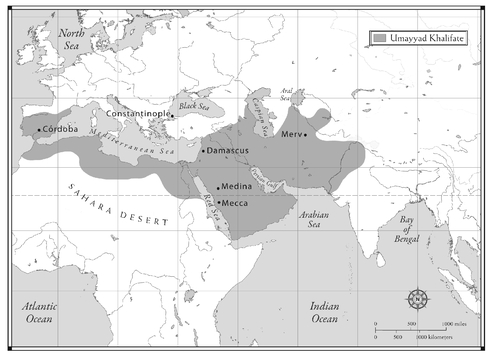

THE UMAYYAD EMPIRE

Worldly tough guys though they were, the Umayyads nurtured the religious institutions of Islam. They supported scholars and religious thinkers, built mosques, and enforced laws that allowed the Islamic way of life to flourish.

Under the Umayyads, it wasn’t just Arab-inspired commercial energy that permeated the Muslim world but also Islam-inspired social ideals. Nouveau riche lords made abundant donations to philanthropic religious foundations called

waqfs.

Social pressure drove them to it, but so did religious incentives: everyone wants the esteem of his or h

er society, and a rich man could garner such esteem by patronizing a waqf.

waqfs.

Social pressure drove them to it, but so did religious incentives: everyone wants the esteem of his or h

er society, and a rich man could garner such esteem by patronizing a waqf.

In theory, a waqf could not be shut down by its founder. Once born, it owned itself and had a sovereign status. Think of it as a Muslim version of a nonprofit corporation set up for charitable purposes. Under Muslim law, the waqfs could not be taxed. They collected money from donors and distributed it to the poor, built and ran mosques, operated schools, hospitals, and orphanages, and generally provided the burgeoning upper classes with a means for expressing their religious and charitable urges and to feel good about themselves even while lolling in wealth.

Of course, someone had to administer a waqf. Someone had to conduct its business, set its policies, and manage its finances, and it couldn’t be just anyone. To possess religious credibility, a waqf had to be staffed by people known for piety and religious learning. The more famously religious its staff, the more prestigious the waqf and the more respect accrued to its founders and donors.

Since the waqfs ended up controlling real estate, buildings, and endowment funds, their management offered an avenue of social mobility in Muslim society (even though many waqfs became a device by which rich families protected their wealth from taxation). If you acquired a reputation for religious scholarship, you might hope to gain a position with a waqf

,

which gave you status if not riches, and you didn’t have to hail from a famous family to become a famous religious scholar. You just had to have brains and a willingness to practice piety and study hard.

,

which gave you status if not riches, and you didn’t have to hail from a famous family to become a famous religious scholar. You just had to have brains and a willingness to practice piety and study hard.

On the other hand, you did have to know Arabic, because it was the sacred language: to Muslims, the Qur’an itself, in Arabic, written or spoken, is the presence of God in the world: translations of the Qur’an are not the Qur’an. Besides, all the pertinent scholarly books were written in Arabic. And you did, of course, have to be Muslim. What’s more, the Umayyads soon declared Arabic the official language of government, replacing Persian in the east and Greek in the west and various local languages everywhere else. So Umayyad times saw an Arabization and Islamification of the Muslim realm.

When I say Islamification, I mean that growing numbers of people in territories ruled by the khalifa abandoned their previous faiths—Zoroastrian, Christian, pagan, or whatever—and converted to Islam. Some no doubt converted to evade the poll tax on non-Muslims, but this probably wasn’t the whole story, because after conversion people were liable for the charity tax incumbent on Muslims but not on non-Muslims.

Some may have converted in pursuit of career opportunities, but this, too, can be overstated, because conversion really only opened up the religion-related careers. The unconverted could still own land, operate workshops, sell goods, and pursue business opportunities. They could work for the government too, if they had skills to offer. The Muslim elite did not hesitate to take from each according to his abilities. If you knew medicine, you could be a doctor; if you knew building, you could be an architect. In the Islamic empire, you could become rich and famous even if you were a C

hristian or a Jew, the “Abrahamic” religions, or eventually Zoroastrian, even though this was more distant from Islam.

hristian or a Jew, the “Abrahamic” religions, or eventually Zoroastrian, even though this was more distant from Islam.

But most people, I think, in the world Muslims came to rule, converted to Islam because it looked like the Truth. Certainly, no other force or movement in the Middle World at this time had the muscular self-confidence and the aura of inexorable success of Islam. Who would

not

want to join the Umma if they could?

not

want to join the Umma if they could?

Other books

The Girls She Left Behind by Sarah Graves

Gabriel's Promise (A Romantic Comedy) by Silver, Jordan

Lie to Me (A Touched Trilogy) by Angela Fristoe

Caught on Camera by Meg Maguire

A Slow Boil by Karen Winters

Unbound: The Pentagon Group, Book 2 by Rosemary Rey

Far After Gold by Jen Black

The Birthmark by Beth Montgomery

400 Boys and 50 More by Marc Laidlaw

Hollywood Animal by Joe Eszterhas