Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (18 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

6.52Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Let me emphasize that the ulama were not (and are not) appointed by anyone. Islam has no pope and no official clerical apparatus. How, then, did someone get to be a member of the ulama? By gaining the respect of people who were already established ulama. It was a gradual p

rocess. There was no license, no certificate, no “shingle” to hang up to prove that one was an alim. The ulama were (and are) a self-selecting, self-regulating class, bound entirely by the river of established doctrine. No single alim could modify this current or change its course. It was too old, too powerful, too established, and besides, no one could become a member of the ulama until he had absorbed the doctrine so thoroughly that it had become a part of him. By the time a person acquired the status to question the doctrine, he would have no inclination to do so. Incorrigible dissenter

s who simply would not stop questioning the doctrine probably wouldn’t make it through the process. They would be weeded out early. The process by which the ulama self-generates makes it an inherently conservative class.

THE PHILOSOPHERSrocess. There was no license, no certificate, no “shingle” to hang up to prove that one was an alim. The ulama were (and are) a self-selecting, self-regulating class, bound entirely by the river of established doctrine. No single alim could modify this current or change its course. It was too old, too powerful, too established, and besides, no one could become a member of the ulama until he had absorbed the doctrine so thoroughly that it had become a part of him. By the time a person acquired the status to question the doctrine, he would have no inclination to do so. Incorrigible dissenter

s who simply would not stop questioning the doctrine probably wouldn’t make it through the process. They would be weeded out early. The process by which the ulama self-generates makes it an inherently conservative class.

The ulama, however, were not the only intellectuals of Islam. While they constructed the edifice of doctrine, another host of thoughtful Muslims were hard at work on another vast project: interpreting all previous philosophies and discoveries in light of the Muslim revelations and integrating them into a single coherent system that made sense of nature, the cosmos, and man’s place in all of it. This project generated another group of thinkers known to the Islamic world as the philosophers.

The expansion of Islam had brought Arabs into contact with the ideas and achievements of many other peoples including the Hindus of India, the central Asian Buddhists, the Persians, and the Greeks. Rome was virtually dead by this time, and Constantinople (for all its wealth) had degenerated into a wasteland of intellectual mediocrity, so the most original thinkers still writing in Greek were clustered in Alexandria, which fell into Arab hands early on. Alexandria possessed a great library and numerous academies, making it an intellectual capital of the Greco-Roman world.

Here, the Muslims discovered the works of Plotinus, a philosopher who had said that everything in the universe was connected like the parts of a single organism, and all of it added up to a single mystical One, from which everything had emanated and to which everything would return.

In this concept of the One, Muslims found a thrilling echo of Prophet Mohammed’s apocalyptic insistence on the oneness of Allah. Better yet,

when they looked into Plotinus, they found that he had constructed his system with rigorous logic from a small number of axiomatic principles, which aroused the hope that the revelations of Islam might be prova

ble with logic.

when they looked into Plotinus, they found that he had constructed his system with rigorous logic from a small number of axiomatic principles, which aroused the hope that the revelations of Islam might be prova

ble with logic.

Further exploration revealed that Plotinus and his peers were merely the latest exponents of a line of thought going back a thousand years to a much greater Athenian philosopher named Plato. And from Plato, the

Muslims went on to discover the whole treasury of Greek thought, from the pre-Socratics to Aristotle and beyond.

Muslims went on to discover the whole treasury of Greek thought, from the pre-Socratics to Aristotle and beyond.

The Abbasid aristocracy took great interest in all of these ideas. Anyone who could translate a book from

Greek, Sanskrit, Chinese, or Persian into Arabic could get high-paying work. Professional translators flocked to Baghdad. They filled whole libraries in the capital and in other major cities with classic texts

translated from other languages. Muslims were the first intellectuals ever in a position to make direct comparisons between, say, Greek and Indian mathematics, or Greek and Indian medicine, or Persian and Chinese cosmologies, or t

he metaphysics of various cultures. They set to work exploring how these ancient ideas fit in with each other and with the Islamic revelations, how spirituality related to reason, and how heaven and earth could

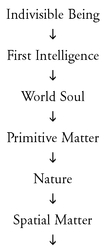

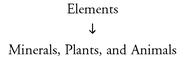

be drawn into a single schema that explained the entire universe. One such schema, for example, described the universe as emanating from pure Being in a series of waves that descended to the material facts of immediate daily life—

like so:

Greek, Sanskrit, Chinese, or Persian into Arabic could get high-paying work. Professional translators flocked to Baghdad. They filled whole libraries in the capital and in other major cities with classic texts

translated from other languages. Muslims were the first intellectuals ever in a position to make direct comparisons between, say, Greek and Indian mathematics, or Greek and Indian medicine, or Persian and Chinese cosmologies, or t

he metaphysics of various cultures. They set to work exploring how these ancient ideas fit in with each other and with the Islamic revelations, how spirituality related to reason, and how heaven and earth could

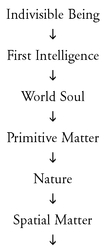

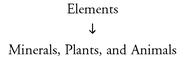

be drawn into a single schema that explained the entire universe. One such schema, for example, described the universe as emanating from pure Being in a series of waves that descended to the material facts of immediate daily life—

like so:

Plato had described the material world as an illusory shadow cast by a “real” world that consisted of unchangeable and eternal “forms”: thus, every real chair is but an imperfect copy of some single “ideal” chair that exists only in the realm of universals. Following from Plato, the Muslim philosophers proposed that each human being was a mixture of the real and the illusory. Before birth, they explained, the soul dwelt in a realm of Platonic universals. In life, it got intertwined with body, which was made up of matter. At death, the two separated, the body returning to the wo

rld of all matter while the soul returned to Allah, its original home.

rld of all matter while the soul returned to Allah, its original home.

For all their devotion to Plato, the Muslim philosophers had tremendous admiration for Aristotle, as well: for his logic, his techniques of classification, and his powerful grasp of particularities. Following from Aristotle, the Muslim philosophers categorized and classified with obsessive logic. Just to give you a taste of this attitude: the philosopher al-Kindi described the material universe in terms of five governing principles: matter, form, motion, time, and space. He analyzed each of these into subcategories, div

iding motion, for instance, into six types: generation, corruption, increase, decrease, change in quality, and change in position. He went on and on like this, intent on parsing all of reality into discrete, understandable parts.

iding motion, for instance, into six types: generation, corruption, increase, decrease, change in quality, and change in position. He went on and on like this, intent on parsing all of reality into discrete, understandable parts.

The great Muslim philosophers associated spirituality with rationality: our essence, they said, was made up of abstractions and principles, which only reason could access. They taught that the purpose of knowledge was to purify the soul by conducting it from sensory data to abstract principles, from particular facts to universal truths. The philosopher al-Farabi was typical in recommending that students begin with the study of nature, move on to the study of logic, and proceed at last to the most abstract of all the disciplines, mathematics.

The Greeks invented geometry, Indian mathematicians came up with the brilliant idea of treating zero as a number, the Babylonians discovered the idea of place value, and the Muslims systematized all of these ideas, adding a few of their own, to invent algebra and indeed to lay the foundations of modern mathematics.

On the other hand, their interests directed the philosophers into practical concerns. By compiling, cataloging, and cross-referencing medical discoveries from many lands, thinkers like Ibn Sina (Avicenna to the Europeans) achieved a near-modern understanding of illness and medical treatments as well as of anatomy—the circulation of blood was known to them, as was the function of the heart and of most other major organs. The Muslim world soon boasted the best hospitals the world had ever seen or was to see for centuries to come: Baghdad alone had some hundred of these facilities.

These Abbasid-era Muslim philosophers also laid the foundations of chemistry as a discipline and wrote treatises on geology, optics, botany, and virtually all the fields of study now known as science. They didn’t call it by a separate name. As in the West, where science was long called natural philosophy, they saw no need to sort some of their speculations into a separate category and call it by a new name, but early on they recognized quantification as an instrument for studying nature, which is one of the cornerstones of science as a stand-alone endeavor. They also relied o

n observation for data upon which to base theories, a second cornerstone of science. They never articulated the scientific method per se—the idea of incrementally building knowledge by formulating hypotheses and then setting up experiments to prove or disprove them. Had they bridged that gap, science as we know it might well have sprouted in the Muslim world in Abbasid times, seven centuries before its birth in western Europe.

n observation for data upon which to base theories, a second cornerstone of science. They never articulated the scientific method per se—the idea of incrementally building knowledge by formulating hypotheses and then setting up experiments to prove or disprove them. Had they bridged that gap, science as we know it might well have sprouted in the Muslim world in Abbasid times, seven centuries before its birth in western Europe.

It didn’t happen, however, for two reasons, one of which involves the interaction between science and theology. In its early stages, science is inherently difficulty to disentangle from theology. Each seems to have implications for the other, at least to its practitioners. When Galileo promoted the theory that the earth goes around the sun, religious authorities put him on trial for heresy. Even today, even in the West, some Christian conservatives counterpose the biblical narrative of creation to the theory of evolution, as if these two are competing explanations of the same

riddle. Science challenges religion because it insists on the reliability and sufficiency of its method for seeking truth: experimentation and reason without recourse to revelation. In the West, for most people, the two fields have reached a compromise by agreeing to distinguish their fields of inquiry: the princ

iples of nature belong to science, the realm of moral and ethical value belongs to religion and philosophy.

riddle. Science challenges religion because it insists on the reliability and sufficiency of its method for seeking truth: experimentation and reason without recourse to revelation. In the West, for most people, the two fields have reached a compromise by agreeing to distinguish their fields of inquiry: the princ

iples of nature belong to science, the realm of moral and ethical value belongs to religion and philosophy.

In ninth and tenth century Iraq (as in classical Greece), science as such did not exist to be disentangled from religion. The philosophers were giving birth to it without quite realizing it. They thought of religion as their field of inquiry and theology as their intellectual specialty; they were on a quest to understand the ultimate nature of reality. That (they said) was what both religion and philosophy were about at the highest level. Anything they discovered about botany or optics or disease was a by-product of this core quest, not its central object. As such, philosophers who

were making discoveries about botany, optics, or medicine did not hesitate to pronounce on questions we moderns would consider theological and quite outside the purview of, say, a chemist or a veterinarian—questions such as this one:

were making discoveries about botany, optics, or medicine did not hesitate to pronounce on questions we moderns would consider theological and quite outside the purview of, say, a chemist or a veterinarian—questions such as this one:

If a man commits a grave sin, is he a non-Muslim, or is he (just) a bad Muslim?

The question might seem like a semantic game, except that in the Muslim world, as a point of law, the religious scholars divided the world between the community and the nonbelievers. One set of rules applied among believers, another set for interactions between believers and nonbelievers. It was important, therefore, to know if any particular person was

in

the community or outside it.

in

the community or outside it.

Some philosophers who took up this question said Muslims who were grave sinners might belong to a third zone, situated between belief and unbelief. The more rigid, mainstream scholars didn’t like the idea of a third zone, because it suggested that the moral universe wasn’t black-and-white but might have shades of gray.

Out of this third-zone concept developed a whole school of theologians called the Mu’tazilites, Arabic for “secessionist,” so called because they had seceded from the mainstream of religious thought, at least according to the orthodox ulama. Over time, these theologians formulated a coherent set of religious precepts that appealed to the philosophers. They said the core of Islam was the belief in

tawhid

: the unity, singleness, and universality of Allah. From this, they argued that the

Qur’an could not be eternal and uncreated (as the ulama proclaimed) because if it were, the Qur’an would constitute a second divine entity alongside Allah, and that would be blasphemy. They argued, therefore, that the Qur’an was among Allah’s creations, just like human beings, stars, and oceans. It was a great book, but it was a book. And if it was just a book, the Qur’an could be interpreted and even (gasp) amended.

tawhid

: the unity, singleness, and universality of Allah. From this, they argued that the

Qur’an could not be eternal and uncreated (as the ulama proclaimed) because if it were, the Qur’an would constitute a second divine entity alongside Allah, and that would be blasphemy. They argued, therefore, that the Qur’an was among Allah’s creations, just like human beings, stars, and oceans. It was a great book, but it was a book. And if it was just a book, the Qur’an could be interpreted and even (gasp) amended.

Tawhid, they went on to say, prohibited thinking of Allah as having hands, feet, eyes, etc., even though the Qur’an spoke in these terms: all such anthropomorphic references in the Qur’an had to be taken as metaphorical language.

God, they went on to say, did not have attributes, such as justice, mercy, or power: ascribing attributes to God made Him analyzable into parts, which violated tawhid

—

unity. God was a single indivisible whole too grand for the human mind to perceive or imagine. What human beings called the attributes of God only named the windows through which humans saw God. The attributes we ascribe to Allah, the Mu’tazilites said, were actually only descriptions of ourselves.

—

unity. God was a single indivisible whole too grand for the human mind to perceive or imagine. What human beings called the attributes of God only named the windows through which humans saw God. The attributes we ascribe to Allah, the Mu’tazilites said, were actually only descriptions of ourselves.

From their conception of Allah, the Mu’tazilites derived the idea that good and evil, right and wrong, were aspects of the unchanging reality of God, reflecting deep principles that humans could discover in the same way that human beings could discover the principles of nature. In short, this or that behavior wasn’t good because scripture said so. Scripture mandated this or that behavior because it was good, and if it was already good before scripture said so, then it was good for some reason inherent to itself, some reason that reason could discover. Reason, therefore, was itself a valid inst

rument for discovering ethical, moral, and political truth

independently of revelation

, according to the Mu’tazilites.

rument for discovering ethical, moral, and political truth

independently of revelation

, according to the Mu’tazilites.

Other books

Tower of Trials: Book One of Guardian Spirit by Jodi Ralston

Darkness the Color of Snow by Thomas Cobb

Meeting at Infinity by John Brunner

The Man Who Built the World by Chris Ward

Thrill Me by Susan Mallery

Clawback by J.A. Jance

Keeping the Moon by Sarah Dessen

Catch a Falling Star by Jessica Starre

The Virtuous Assassin by Anne, Charlotte