Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (21 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

13.88Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In that cataclysmic transition, the new rulers lured all the Umayyads into a room and clubbed them to death. Well, not quite all. One Umayyad nobleman skipped the party. This man, the last of the Umayyads, a young fellow by the name of Abdul Rahman, fled Damascus in disguise and headed across North Africa, and he didn’t stop running until he got to the furthest tip of the Muslim world: Andalusian Spain. Any further and he would have been in the primitive wilderness of Christian Europe.

Abdul Rahman impressed the locals in Spain. A few hard-core Kharijite insurgent types skulking about there at the ends of the Earth pledged their swords to the youngster. There in Spain, so far from the Muslim heartland, no one knew much about the new regime in Baghdad and certainly felt no loyalty to them. Andalusians were accustomed to thinking of the Umayyads as rulers, and here was a real-life Umayyad asking to be their ruler. In a less tumultuous time, Abdul Rahman might simply have been posted here as governor and the people would have accepted him. Therefore, they accepted h

im as their leader now, and Andalusian Spain became an independent state, separate from the rest of the khalifate. So the Muslim story was now unfolding from two centers.

im as their leader now, and Andalusian Spain became an independent state, separate from the rest of the khalifate. So the Muslim story was now unfolding from two centers.

At first, this was only a political fissure, but as the Abbasids weakened, the Andalusian Umayyads announced that they were not merely independent of Baghdad but were, in fact, still the khalifas. Everyone within a few hundred miles said, “Oh, yes, sir, you’re definitely the khalifa of Islam; we could tell from the very look of you.” So the khalifate itself, this quasi-mystical idea of a single worldwide community of faith, was broken in two.

The Umayyad claim had some resonance because their Andalusian capital of Córdoba was far and away the greatest city in Europe. At its height i

t had some half a million inhabitants and boasted hundreds of bathhouses, hospitals, schools, mosques, and other public buildings. The largest of many libraries in Córdoba reputedly contained some five hundred thousand volumes. Spain had other urban centers as well, cities of fifty thousand or more at a time when the biggest towns in Christian Europe did not exceed twenty-five thousand inhabitants. Once-mighty Rome was merely a village now, with a population smaller than Dayton, Ohio, a thin smattering of peasants and ruffians eking out a living among the ruins.

t had some half a million inhabitants and boasted hundreds of bathhouses, hospitals, schools, mosques, and other public buildings. The largest of many libraries in Córdoba reputedly contained some five hundred thousand volumes. Spain had other urban centers as well, cities of fifty thousand or more at a time when the biggest towns in Christian Europe did not exceed twenty-five thousand inhabitants. Once-mighty Rome was merely a village now, with a population smaller than Dayton, Ohio, a thin smattering of peasants and ruffians eking out a living among the ruins.

At first, therefore, the political split in Islam did not seem to imply any loss of civilizational momentum. Andalusia traded heavily with the rest of the civilized world. It sent timber, grains, metals, and other raw materials into North Africa and across the Mediterranean to the Middle World, importing from those regions handcrafted luxury goods, ceramics, furniture, rich textiles, spices and the like.

Trade with the Christian countries to the north and east, by contrast, amounted to a mere trickle—not so much because of any hostility between the regions, but because Christian Europeans had virtually nothing to sell and no money with which to buy.

Muslims formed the majority in Andalusia, but many Christians and Jews lived there as well. Umayyad Spain may have been at odds with the Baghdad khalifate, but its rulers followed much the same social policies as in all the Muslim conquests so far. Both Christian and Jewish communities had their own religious leaders and judicial systems and were free to practice their own rituals and customs. If one of them got into a dispute with a Muslim, the case was tried in a Muslim court by Islamic rules but disputes among themselves were adjudicated by their own judges according to their own rules.

Non-Muslims had to pay the poll tax but were exempt from the charity tax

.

They were excluded from military service and the highest political positions, but all other occupations and offices were open to them. Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived in fairly amicable harmony in this empire with the caveat that Muslims wielded ultimate political power and probably radiated an attitude of superiority, stemming from certainty that their culture and society represented the highest stage of civilization, much as Americans and western Europeans now tend to do vis-à-vis people of third world countries.

.

They were excluded from military service and the highest political positions, but all other occupations and offices were open to them. Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived in fairly amicable harmony in this empire with the caveat that Muslims wielded ultimate political power and probably radiated an attitude of superiority, stemming from certainty that their culture and society represented the highest stage of civilization, much as Americans and western Europeans now tend to do vis-à-vis people of third world countries.

The story of King Sancho illustrates how the various communities got along. In the late tenth century CE, Sancho inherited the throne of Leon, a Christian kingdom north of Spain. Sancho’s subjects soon began referring to him as Sancho the Fat, the sort of nickname a king never likes to hear his subjects using with impunity. Poor Sancho might more accurately have been called Sancho the Medically Obese, but his nobles could not take the large view. They regarded Sancho’s size as proof of an internal weakness that made him unfit to rule, so they deposed him.

Sancho then heard about a Jewish physician named Hisdai ibn Shaprut who reputedly knew how to cure obesity. Hisdai was employed by the Muslim ruler in Córdoba, so Sancho headed south with his mother and retinue to seek treatments. The Muslim ruler Abdul Rahman the Third welcomed Sancho as an honored guest and had him stay at the royal palace until Hisdai had shrunk him down, whereupon Sancho returned to Leon, reclaimed his throne, and signed a treaty of friendship with Abdul Rahman.

1

1

A Christian king received treatments from a Jewish physician at the court of a Muslim ruler: there you have the story of Muslim Spain in a nutshell. When Europeans talk about the Golden Age of Islam, they are often thinking of the Spanish khalifate, because this was the part of the Muslim world that Europeans knew the most about.

But Córdoba was not the only city to rival Baghdad. In the tenth century, another city emerged to challenge the supremacy of the Abbasid khalifate.

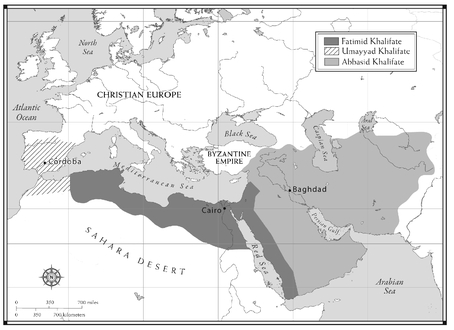

When the Abbasids decided to rule as Sunnis, they revived the Shi’ite impulse to rebellion. In 347 AH (969 CE) Shi’i warriors from Tunisia managed to seize control of Egypt and declared themselves the true khalifas of Islam because (they said) they were descended from the Prophet’s daughter Fatima, for which reason they called themselves the Fatimids. These rulers built themselves a brand new capital they called Qahira, the Arabic word for “victory.” In the West, it is spelled Cairo.

The Egyptian khalifate had the resources of North Africa and the granaries of the Nile valley to draw upon. It was well situated to compete in the Mediterranean Sea trade, and it dominated the routes along the Red Sea to Yemen, which gave it access to markets bordering the Indian Ocean. By the year 1000 CE, it probably outshone both Baghdad and Córdoba.

In Cairo, the Fatimids built the world’s first university, Al Azhar, which is still going strong. Everything I’ve said about the other two khalifates—big

cities, busy bazaars, liberal policies, lots of cultural and intellectual activity—was true of this khalifate as well. Rich as it was, however, Egypt represented yet another fragmentation of what was, in theory, a single universal community. In short, as the millennium approached, the Islamic world was divided into three parts.

cities, busy bazaars, liberal policies, lots of cultural and intellectual activity—was true of this khalifate as well. Rich as it was, however, Egypt represented yet another fragmentation of what was, in theory, a single universal community. In short, as the millennium approached, the Islamic world was divided into three parts.

THE THREE KHALIFATES

Each khalifate asserted itself to be the one and only true khalifate—“one and only” being built into the very meaning of the word

khalifate.

But since the khalifas were really merely secular emperors by this time, the three khalifates more or less coexisted, just like three vast secular states.

khalifate.

But since the khalifas were really merely secular emperors by this time, the three khalifates more or less coexisted, just like three vast secular states.

The Abbasids had the most territory (at first), and theirs was the richest capital, but the very size of their holdings made them, in some ways, the weakest of the three khalifates. Just as Rome grew too big to administer from any single place by any single ruler, so, too, did the Abbasid khalifate. A vast bureaucracy that developed to carry out the khalifa’s orders encrusted into permanence. The khalifa disappeared into the stratosphere above this machinery of state until he became invisible to his subjects.

Just like the Roman emperors, the Abbasid khalifas surrounded themselves with a corps of bodyguards, which became the tail tha

t wagged the dog. In Rome, this group was called the Praetorian Guard, and it was (ironically) well staffed with Germans recruited from the territories of the barbarians north of the frontiers, those same barbarians with whom Rome had been at war for centuries and whose excursions posed a constant threat to civilized order.

t wagged the dog. In Rome, this group was called the Praetorian Guard, and it was (ironically) well staffed with Germans recruited from the territories of the barbarians north of the frontiers, those same barbarians with whom Rome had been at war for centuries and whose excursions posed a constant threat to civilized order.

The same pattern emerged in the Abbasid khalifate. Here, the imperial guards were called mamluks, which means “slaves,” although these were not ordinary slaves but elite slave soldiers. Like Rome, the Abbasid khalifate was plagued by nomadic barbarians north of its borders. In the west, the barbarians of the north were Germans; here they were Turks. (There were no Turks in what is now called Turkey; they migrated to this area much later. The ancestral home of the Turkish tribes was the central Asian steppes north of Iran and Afghanistan.) As the Romans had done with the Germ

ans, the Abbasids imported some of these Turks—purchasing them from the slave markets along the frontier—and used them as bodyguards. The khalifas did this because they didn’t trust the Arabs and Persians whom they ruled and among whom they lived, folks with too many local roots, too many relatives, and interests of their own to push. The khalifas wanted guards with no links to anyone but the khalifas themselves, no home but their court, no loyalties except to their owners. Therefore, the slaves they brought in were children. They had these kids raised as Muslims in special schools where they were taught mar

tial skills. When they grew up they entered an elite corps that formed something like an extension of the khalifa’s own identity. In fact, since the public never saw the khalifa anymore, these Turkish bodyguards became, for most folks, the face of the khalifate.

ans, the Abbasids imported some of these Turks—purchasing them from the slave markets along the frontier—and used them as bodyguards. The khalifas did this because they didn’t trust the Arabs and Persians whom they ruled and among whom they lived, folks with too many local roots, too many relatives, and interests of their own to push. The khalifas wanted guards with no links to anyone but the khalifas themselves, no home but their court, no loyalties except to their owners. Therefore, the slaves they brought in were children. They had these kids raised as Muslims in special schools where they were taught mar

tial skills. When they grew up they entered an elite corps that formed something like an extension of the khalifa’s own identity. In fact, since the public never saw the khalifa anymore, these Turkish bodyguards became, for most folks, the face of the khalifate.

Of course they were arrogant, violent, and rapacious—they were raised to be. Even while keeping the khalifa safe, they alienated him from his people, their depredations making him ever more unpopular and therefore unsafe and therefore ever more in need of bodyguards. Eventually, the khalifa had to build the separate soldier’s city of Samarra just to house his troublesome mamluks, and he himself moved there to live among them.

Meanwhile, a Persian family, the Buyids, insinuated themselves into the court as the khalifa’s advisers, clerks, helpers. Soon, they took control of the bureaucracy and thus of the empire’s day-to-day affairs. Boldly, they passed the office of vizier (chief administrator) down from father to son as a h

ereditary title. (A similar thing happened in the Germanic kingdoms of Europe where a similar officer, the “mayor of the palace” developed into the real ruler of the land.) The Buyids, like the khalifas, began importing the children of Turkish barbarians to Baghdad as slaves and raising them in dormitories over which they had absolute control, to serve as

their

personal bodyguards. Once the Buyids had their system in place, no one could oppose them, for their Turkish bodyguards had come to town at such a young age they had no memory of their families, their fathers, their mothers, their

siblings: they knew only the camaraderie of the military schools and camps in which they grew up, and they felt soldierly allegiance only to one another and to the men who had controlled their lives in the camps. The Buyids, then, became a new kind of dynasty in Islam. They kept the khalifa in place but issued orders in his name and enjoyed a high life behind the throne. Thus, Persians came to rule the capital of the Arab khalifate.

ereditary title. (A similar thing happened in the Germanic kingdoms of Europe where a similar officer, the “mayor of the palace” developed into the real ruler of the land.) The Buyids, like the khalifas, began importing the children of Turkish barbarians to Baghdad as slaves and raising them in dormitories over which they had absolute control, to serve as

their

personal bodyguards. Once the Buyids had their system in place, no one could oppose them, for their Turkish bodyguards had come to town at such a young age they had no memory of their families, their fathers, their mothers, their

siblings: they knew only the camaraderie of the military schools and camps in which they grew up, and they felt soldierly allegiance only to one another and to the men who had controlled their lives in the camps. The Buyids, then, became a new kind of dynasty in Islam. They kept the khalifa in place but issued orders in his name and enjoyed a high life behind the throne. Thus, Persians came to rule the capital of the Arab khalifate.

These Persian viziers couldn’t rule the rest of the empire, however, nor did they even care to. They were perfectly content to leave distant locales to the domination of whatever lord happened to have the most strength there. Major governors thus turned into minor kings, and Persian mini dynasties proliferated across the former Sassanid realm.

You might think that training slaves to be killers, giving them weapons, and then stationing them outside your bedroom door would be such a bad idea that no one would ever do it, but in fact almost everyone did it in these parts: every little breakaway Persian kingdom had its own corps of Turkish mamluks guarding and eventually controlling its little Persian king.

As if that were not enough, the empire as a whole was constantly fighting to keep whole tribes of Turkish nomads from crossing the frontier and wreaking havoc in the civilized world, just as the Romans had struggled to keep the Germans at bay. At last the Turks grew too strong to suppress, both inside and outside the khalifate. In some of those little outlying kingdoms, mamluks killed their masters and founded their own dynasties.

Meanwhile, with the empire decaying and the social fabric fraying, barbarians began to penetrate the northern borders, much as the Germans had done in Europe when they crossed the Rhine River into Roman territory. Rude Turks came trickling south in ever growing numbers: tough warriors, newly converted to Islam and brutal in their simplistic fanaticism. Accustomed to plunder as a way of life, they ruined cities and la

id waste to crops. The highways grew unsafe, small-time banditry became rife, trade declined, poverty spread. Turkish mamluks fought bitterly with Turkish nomads—it was Turks in power everywhere. This is part of why anxiety permeated the empire in Ghazali’s day.

id waste to crops. The highways grew unsafe, small-time banditry became rife, trade declined, poverty spread. Turkish mamluks fought bitterly with Turkish nomads—it was Turks in power everywhere. This is part of why anxiety permeated the empire in Ghazali’s day.

Other books

Adjournment (The Fate Series) by Emersyn Vallis

Six Bad Things by Charlie Huston

Captive Ride by Ella Goode

Survival Colony 9 by Joshua David Bellin

For Fallon by Soraya Naomi

Flameseeker (Book 3) by R.M. Prioleau

Time Bomb by Jonathan Kellerman

Looking Back From L.A. by M. B. Feeney

You Better Not Cry: Stories for Christmas by Augusten Burroughs