Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (24 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

5.01Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Every generation therefore saw a larger pool of landless noblemen for whom there was no suitable occupation except war, and with the invasions sloping off, there wasn’t even enough war to go around. The Vikings, the last major wave of invaders, no longer posed a threat because, by the eleventh century they had crammed into Europe and settled down. “They” had become “us.” Even so, the system kept producing knights and more knights.

Enter the pilgrims, stage left, complaining of the indignities visited upon them by heathens in the Holy Lands. Finally, in 1095, Pope Urban II delivered a fiery open-air speech outside a French monastery called Claremont. There, he told an assembly of French, German, and Italian nobles that Christendom was in danger. He detailed the humiliations that Christian pilgrims had suffered in the Holy Lands and called upon men of faith to help their brethren expel the Turks from Jerusalem. Urban suggested that those who headed east should wear a cross-shaped red patch as a badge of their

quest. The expedition was to be called a

croisade,

from

croix,

French for “cross,” and from this came the name historians give to this whole undertaking: the Crusades.

quest. The expedition was to be called a

croisade,

from

croix,

French for “cross,” and from this came the name historians give to this whole undertaking: the Crusades.

By focusing on Jerusalem, Urban linked the invasion of the east to pilgrimage, thus framing it as a religious act. Therefore, by the authority vested in him as pope, he decreed that anyone who went to Jerusalem to kill Muslims would receive partial remission of his sins.

One can only imagine how this must have struck those thousands of restless, rowdy, psychologically desperate European knights: “Go east, young man,” the pope was saying. “Unleash your true self as the awesome killing machine your society trained you to be, stuff your pockets with gold guilt-free, get the land you were born to own, and as a consequence of it all—get into heaven after you’re dead!”

When the first crusaders came trickling into the Muslim world, the locals had no idea who they were dealing with. Early on, they assumed the interlopers to be Balkan mercenaries working for the emperor in Constantinople. The first Muslim ruler to encounter them was a Seljuk prince, Kilij Arslan, who ruled eastern Anatolia from the city of Nicaea, about three days’ journey from Constantinople. One day in the summer of 1096, Prince Arslan received information that a crowd of odd-looking warriors had entered his territory, odd because they were so poorly outfitted: a few did loo

k like warriors, but the rest seemed like camp followers of some kind. Almost all wore a cross-shaped patch of red cloth sewn to their garments. Arslan had them followed and watched. He learned that these people called themselves the Franks; local Turks and Arabs called them al-Ifranj (“the Franj”). The interlopers openly proclaimed that they had come from a distant western land to kill Muslims and conquer Jerusalem, but first they intended to take possession of Nicaea. Arslan plotted ou

t the route they seemed to be taking, laid an ambush, and smashed them like so many ants, killing many, capturing many more, and chasing the rest back into Byzantine lands. It was so easy that he gave them no more thought.

k like warriors, but the rest seemed like camp followers of some kind. Almost all wore a cross-shaped patch of red cloth sewn to their garments. Arslan had them followed and watched. He learned that these people called themselves the Franks; local Turks and Arabs called them al-Ifranj (“the Franj”). The interlopers openly proclaimed that they had come from a distant western land to kill Muslims and conquer Jerusalem, but first they intended to take possession of Nicaea. Arslan plotted ou

t the route they seemed to be taking, laid an ambush, and smashed them like so many ants, killing many, capturing many more, and chasing the rest back into Byzantine lands. It was so easy that he gave them no more thought.

He didn’t know that this “army” was merely the ragtag vanguard of a movement that would plague Muslims of the Mediterranean coast for another two centuries. While Urban had been speaking to the aristocracy up at the monastery, a vagabond named Peter the Hermit had been preaching the same message out on the streets. Urban had addressed nobles and knights, but presumably any Christian who went crusading could get the remission of sins the pope was offering, so Peter the Hermit was able to recruit from all classes—peasants, artisans, tradespeople, even women and children. His “army” left befo

re the formal army could get organized, in part because

his

“army” didn’t feel much need to get organized. They were off to do God’s work; surely God would take care of the arrangements. It was these tens of thousands of cobblers, butchers, peasants and the like that Kilij Arslan succeeded in crushing.

re the formal army could get organized, in part because

his

“army” didn’t feel much need to get organized. They were off to do God’s work; surely God would take care of the arrangements. It was these tens of thousands of cobblers, butchers, peasants and the like that Kilij Arslan succeeded in crushing.

The next year, when Kilij Arslan heard that more Franj were coming, he dismissed the threat with a shrug. But the Crusaders in this next wave were real knights and archers led by combat-hardened military commanders from a land where the combat never stopped. Arslan’s engagement with them came down to a battle of lightly clad mobile horseman firing arrows at the armored tanks that were the medieval knights of western Europe. The Turks picked off the Franj foot soldiers, but the knights formed defensive blocks that arrows could not penetrate and kept moving slowly, ponderously,

and inexorably forward. They took Arslan’s city and sent him running to one of his relatives for refuge. The knights then split up, some heading inland toward Edessa, the rest heading down the Mediterranean coast toward Antioch.

and inexorably forward. They took Arslan’s city and sent him running to one of his relatives for refuge. The knights then split up, some heading inland toward Edessa, the rest heading down the Mediterranean coast toward Antioch.

The king of Antioch sent a desperate appeal to the king of Damascus, a man named Daquq. The king of Damascus wanted to help, but he was nervous about his brother Ridwan, the king of Aleppo, who would swoop in and grab Damascus if Daquq were to leave it. The ruler of Mosul agreed to help, but he got distracted fighting someone else along the way, and when he did arrive—late—he got into a fight with Daquq who had also finally arrived—late—and these two Muslim forces ended up going home without helping Antioch at all. From the Muslim side, this was the story of the early Crusades: a t

ragicomedy of internecine rivalry played o

ut in city after city. When Antioch fell, the knights took vengeance for the city’s resistance with some indiscriminate killing, and then kept heading south, towards a city called Ma’ara.

ragicomedy of internecine rivalry played o

ut in city after city. When Antioch fell, the knights took vengeance for the city’s resistance with some indiscriminate killing, and then kept heading south, towards a city called Ma’ara.

Knowing what had happened at Nicaea and Antioch, the Ma’arans were terrified. They too sent urgent messages to nearby cousins, begging for help, but their cousins were only too glad to see the wolves from the west batter Ma’ara, each one hoping to absorb the city for himself once the Franj had blown by. So Ma’ara had to face the Franj alone.

The Christian knights set siege to the city and reduced it to desperation—but in the process reduced themselves to desperation as well, because they ate every scrap of food in the vicinity and then commenced to starve. Obviously, no one was going to feed these invaders, and that was the problem with setting a long siege in a strange land.

At last Franj leaders sent a message into the city assuring the people of Ma’ra that none of them would be harmed if they simply opened their gates and surrendered. The city notables decided to comply. But once the Crusaders made it into Ma’ara, they did more than slaughter. They went on a frightening rampage that included boiling adult Muslims up for soup and skewering Muslim children on spits, grilling them over open fires, and eating them.

I know this sounds like horrible propaganda that the defeated Muslims might have concocted to slander the Crusaders, but reports of Crusader cannibalism in this instance come from Frankish as well as Arab sources. Frankish eyewitness Radulph of Caen, for example, reported on the boiling and grilling. Albert of Aix, also present at the conquest of Ma’ara, wrote, “Not only did our troops not shrink from eating dead Turks and Saracens; they also ate dogs!”

2

What strikes me about this statement is the implication that eating dogs was worse than eating Turks, which makes me think th

at this Franj, at least, considered Turks a different species from himself.

2

What strikes me about this statement is the implication that eating dogs was worse than eating Turks, which makes me think th

at this Franj, at least, considered Turks a different species from himself.

Amazingly enough, even after this debacle, the Muslims could not unite. Examples abound. The ruler of Homs sent the Franj a gift of horses and offered them advice about what they might sack next (not Homs). The Sunni rulers of Tripoli invited the Franj to make common cause with them against the Shi’i. (Instead, the Franj conquered Tripoli.)

When the Crusaders first arrived, the Egyptian vizier al-Afdal sent a letter to the Byzantine emperor, congratulating him on the “reinforceme

nts” and wishing the Crusaders every success! Egypt had long been locked in a struggle with both the Seljuks and the Abbasids, and al-Afdal really thought the newcomers would merely help his cause. It didn’t seem to dawn on him until too late that he himself might be in the line of pillage. After the Franj conquered Antioch, the Fatimid vizier wrote to them to ask if there was anything he could do to help. When the Franj moved against Tripoli, Afdal took advantage of the distraction to assert control of Jerusalem in the name of the Fatimid khalifa. He posted his own governor there and assu

red the Franj they were now welcome to visit Jerusalem anytime as honored pilgrims: they would have his protection. But the Franj wrote back to say they were not interested in protection but in Jerusalem, and they were coming “with lances raised.”

3

nts” and wishing the Crusaders every success! Egypt had long been locked in a struggle with both the Seljuks and the Abbasids, and al-Afdal really thought the newcomers would merely help his cause. It didn’t seem to dawn on him until too late that he himself might be in the line of pillage. After the Franj conquered Antioch, the Fatimid vizier wrote to them to ask if there was anything he could do to help. When the Franj moved against Tripoli, Afdal took advantage of the distraction to assert control of Jerusalem in the name of the Fatimid khalifa. He posted his own governor there and assu

red the Franj they were now welcome to visit Jerusalem anytime as honored pilgrims: they would have his protection. But the Franj wrote back to say they were not interested in protection but in Jerusalem, and they were coming “with lances raised.”

3

The Franj marched through largely empty country, for their reputation had preceded them. Rural folks had fled at their approach, and small towns had emptied into larger cities with higher walls for protection. Jerusalem had some of the highest walls around, but after a forty-day siege, the Crusaders tried the same gambit they had run successfully at Ma’ara—open the gates, no one will be harmed, they told the citizens—and it worked here too.

Upon securing this city, the Franj indulged in an orgy of bloodletting so drastic it made all the previous carnage seem mild. One crusader, writing about the triumph, described piling up heads, hands, and feet in the streets. (He called it a “wonderful sight.”) He spoke of crusaders riding through heathen blood up to their knees and bridle reins.

4

Edward Gibbon, the British historian who chronicled the fall of the Roman Empire, said the Crusaders killed seventy thousand people here over the course of two days. Of the city’s Muslims, virtually none survived.

4

Edward Gibbon, the British historian who chronicled the fall of the Roman Empire, said the Crusaders killed seventy thousand people here over the course of two days. Of the city’s Muslims, virtually none survived.

The city’s Jewish denizens took refuge in their gigantic central synagogue, but while they were in there praying for deliverance, the Crusaders blockaded all the doors and windows and set fire to the building, burning up pretty much the entire Jewish community of Jerusalem in one fell swoop.

The city’s native Christians did not fare so well either. None of them belonged to the Church of Rome but to various Eastern churches such as the Greek, Armenian, Coptic, or Nestorian. The crusading Franj looked upon them as schismatics bordering on heresy, and since heretics were almost worse than heathens, they confiscated the property of these eastern Christians and sent them into exile.

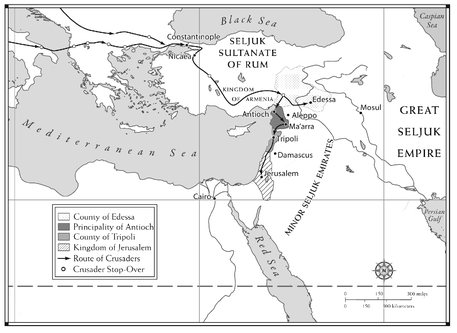

THE THEATER OF THE CRUSADES

The taking of Jerusalem marked the high-water mark of the Franj invasion. The victorious crusaders proclaimed Jerusalem a kingdom. It ranked the highest of the four small crusader states that took root in this area, the others being the principality of Antioch and the counties of Edessa and Tripoli.

Once these four crusader states had been established, a sort of deadlock developed, which ground on dismally for decades. The two sides continued to clash sporadically during these decades, and the Franj won some battles, but they also lost some battles. They pounded the Muslims, but also got pounded, and they quarreled with one another, just as the Muslims were doing among themselves. Sometimes they forged temporary alliances with some Muslim prince to gain an advantage against a rival Franj.

Strange alignments formed and died. In one battle Christian king Tancred of Antioch fought Muslim amir Jawali of Mosul. One third of Tancred’s force that day consisted of Turkish warriors on loan from the Muslim ruler of Aleppo, who was allied with the Assassins, who had links with the Crusaders. On the other side, about one third of Jawali’s

troops were Franj knights on loan from King Baldwin of Edessa, who had a rivalry going with Tancred.

5

And this was typical.

troops were Franj knights on loan from King Baldwin of Edessa, who had a rivalry going with Tancred.

5

And this was typical.

On the Muslim side, the absence of unity was breathtaking. It stemmed partly from the fact that the Muslims saw no ideological dimension to the violence, at first. They felt themselves under attack not as Muslims but as individuals, as cities, as mini states. They experienced the Franj as a horrible but meaningless catastrophe, like an earthquake or a swarm of snakes.

It’s true that after the carnage at Jerusalem, a few preachers tried to arouse Muslim resistance by defining the invasion as a religious war. Several prominent jurists began delivering sermons in which they used the word

jihad

for the first time in ages

,

but their harangues fell flat with Muslim audiences. The word

jihad

merely seemed quaint, for it had fallen out of use centuries earlier, in part because of the rapid expansion of Islam, which had left the vast majority of Muslims living so far from any frontier that they had no enemy to fight in the name of jihad. That early sense of Isl

am against the world had long ago given way to a sense of Islam

as

the world. Most wars that anyone could remember hearing of had been fought for petty prizes such as territory, resources, or power. The few that could be cast as noble struggles about ideals were never about Islam versus something else, but only about whose Islam was the real Islam.

jihad

for the first time in ages

,

but their harangues fell flat with Muslim audiences. The word

jihad

merely seemed quaint, for it had fallen out of use centuries earlier, in part because of the rapid expansion of Islam, which had left the vast majority of Muslims living so far from any frontier that they had no enemy to fight in the name of jihad. That early sense of Isl

am against the world had long ago given way to a sense of Islam

as

the world. Most wars that anyone could remember hearing of had been fought for petty prizes such as territory, resources, or power. The few that could be cast as noble struggles about ideals were never about Islam versus something else, but only about whose Islam was the real Islam.

Given the turmoil of the Muslim world, perhaps some disunity was inevitable: when the Franj dropped into this snake pit, fractious Muslims simply incorporated them into their ongoing dramas. Not all the disunity was spontaneous, however. The Assassins were busy behind the scenes, sowing turmoil, and quite successfully.

Other books

My Special Forces Boyfriend Trilogy by Tiffany Madison

Driven by Susan Kaye Quinn

We'll Meet Again by Mary Higgins Clark

The Loom by Sandra van Arend

High Plains Promise (Love on the High Plains Book 2) by Beaudelaire, Simone

Perfectly Ridiculous by Kristin Billerbeck

Error in Diagnosis by Mason Lucas M. D.

All the King's Men by Robert Marshall

Cutler 3 - Twilight's Child by V.C. Andrews

Breaking The Drought by Lisa Ireland