Drinking Water (30 page)

Recognizing the various facets of drinking water also frames the Cochabamba story in a different light. There were many issues underpinning the unrest in Cochabamba, but the fundamental problem surely did not lie in treating access to water as a market transaction instead of by right. Water was not free before the uprising in Cochabamba, and it is not free now. By granting an exclusive water concession to Aguas del Tunari and requiring that water withdrawals be licensed by the state, the government was perceived as effectively enclosing the “water commons.” Contemporary accounts suggested that people feared the government was outlawing the traditional collection of water from rain barrels, streams, and wells. This likely played a far greater role in people taking to the streets than rising water bills. Such failure to consider the popular conceptions of resource access proved fatal. By treating drinking water as a purely economic resource and focusing on pricing, Aguas del Tunari ignored water’s significant nature as a social resource. The mass demonstrations did call for a return to previous water rates but, more fundamentally, a return to previous entitlements.

When a water system seeks to pay for itself, whether government-run or private, it must decide how to value the provision of water in a culturally acceptable manner. As the Cochabamba case illustrates, where cultures view the right to water as an inherent right, full cost recovery is likely to fail. There still is room for market mechanisms, but they may need to be more creative, mindful of the experiences in India and South Africa.

W

HILE THE PRIVATIZATION DEBATE HAS DOMINATED MUCH OF THE

discussion over drinking water provisions in developing countries, it is by no means the only concern. In fact, it is largely irrelevant for many rural areas. In these places, once one moves outside the big cities, large-scale infrastructure is infeasible and privatization

by large companies with access to capital makes no sense. So what is to be done? In recent years, promising strategies have been developed to reinvent how to ensure safe water in the home and how to pay for it. Neither of these is a silver bullet. The problem is far too large and complicated for that, but they do offer some hope to what can seem an insoluble challenge.

The major pathway of waterborne diseases through drinking water in rural areas follows a well-worn route: inadequate sanitation leads to contaminated water sources. The traditional approach to address this problem has involved infrastructure projects such as digging wells, putting in piped water, and building latrines. The focus, in other words, has been on improving water sources and sanitation. And these are obviously important. They can also be relatively expensive for very poor areas. There’s a reason beyond ignorance that they are not already in place. And even where wells and latrines are in place, there still may be a high incidence of waterborne diseases.

In recent years, researchers have realized that their model of providing clean drinking water to poor households is incomplete in an important respect. Digging a deep well and building latrines away from the water source are all well and good. But if the water is carried home and stored in a dirty container—if it becomes contaminated during transport or storage—then all the previous protections were wasted efforts. Providing clean water to a village is not enough. It must be kept clean until it is drunk by individuals. As a result, there has been a great deal of work studying behavior at the water’s point of use (known as POU).

“POU interventions” is the fancy name for behaviors and technologies in the household to ensure safe drinking water just before consumption. They fall into three broad categories. The first is physically removing pathogens, usually through sedimentation (letting the water settle) or filtration. Filters run the gamut from simply passing water through a cloth rag or sand to more sophisticated membranes, ceramic filters, or even reverse osmosis technologies. The second approach is to disinfect by heat or exposure to ultraviolet radiation. The third approach relies on chemically treating the water with small amounts of iodine or chlorine.

Household chlorination, for example, has proven an effective POU strategy with widespread adoption. It is often dispensed by filling a chlorine container’s bottle cap and pouring it into a standard-sized bucket filled with water. Simply stir, wait, and drink. A popular chlorine-based product in Africa, WaterGuard, is available for sale at a reasonable price. Diarrhea can be reduced by 22 to 84 percent and the cost is low, from 0.01 to 0.05 cents per use. The main downside is the chlorine taste in the water and its inability to kill some common parasites.

Solar disinfection is easy to use in sunny climates. Clear water is placed in plastic bottles and left in the sun for six hours, two days if cloudy. The sun’s ultraviolet radiation kills common germs such as giardia and cryptosporidia. The technique has been disseminated in more than twenty developing countries and currently has more than one million users. While free (apart from the clear bottle) and easy to use, the range of effectiveness is broad, reducing diarrhea by anywhere from 9 to 86 percent.

Another promising POU approach has been developed by the consumer products giant Procter & Gamble. Called Pur, the powdered product is provided in a small sachet. The instructions are straightforward—add the packet to ten liters of water, stir, let the particles settle, strain, wait, and drink. The cost is one penny per liter of water. Procter & Gamble, in partnership with the Children’s Safe Drinking Water program, has distributed over 130 million sachets on a not-for-profit basis since 2004. The main ingredients are ferric sulfate, a compound that binds to particles in the water, and the disinfectant calcium hypochlorite. Procter & Gamble claims that studies conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Johns Hopkins University found diarrhea incidences reduced by half. The major downsides are the multiple steps required to treat the water and the need for mixing equipment, which can be a challenging obstacle in communities where water collection itself can consume hours each day.

These are only a few of the wide range of POU interventions currently under development, but suffice it to say that this is a vibrant field of activity. These experiences and others suggest that

POU treatments can produce major health benefits at a low cost. Indeed, the research on POU raises a fundamental challenge to drinking water strategies more broadly. As an article in the medical journal

BMJ

concluded:

Water quality interventions were effective in reducing diarrhea even in the absence of improved water supplies and sanitation. Effectiveness did not seem to be enhanced by combining the intervention with other common strategies for preventing diarrhea (instruction on basic hygiene, improved water storage, or improved water supplies and sanitation facilities). Although the evidence does not rule out additional benefit from combined interventions, it does raise questions about whether the additional cost of such integrated approaches as currently implemented is warranted on the basis of health gains alone.

In plain English, the authors suggest that POU may be more effective and less expensive than the more traditional strategies for assuring drinking water quality. A major review of POU field studies reached the same conclusion. Providing clean water, improving sanitation, and hand-washing with soap may not significantly reduce waterborne disease any more than the POU intervention

on its own

.

The policy implications of these findings are significant. Assume for a moment that you are the head of development for a funding agency. You have been tasked to reduce the incidence of waterborne disease in a desperately poor group of villages in East Africa with contaminated surface water sources and little or no sanitation. Human and animal waste flow into the local ponds and streams. Protecting the water source and improving sanitation are obviously important priorities for poor communities, but what to do if funds are limited? Your budget is tight, and your bosses want quick results. Where should you invest your resources?

In the past, the traditional approach would have focused on digging wells and building latrines, and these definitely can improve quality of life. But they also require construction, labor, and time. The research described above suggests that focusing on POU interventions

can provide more immediate benefits, to more people, at lower cost. Over the long term, one can reasonably debate about the relative merits of investing in infrastructure versus short-term POU actions (and experts in the field do indeed debate about this), but the low uptake costs of POU make it very attractive to the donor community, where real results can be seen soon after adoption in poor communities suffering from intestinal diseases caused by dirty drinking water, particularly when the likelihood of funds for large-scale centralized treatment and distribution infrastructure is remote.

Adoption, though, is the key word. Developing effective POU interventions is one thing; ensuring they are used, and used appropriately, is quite another. Changing people’s behavior is no easy matter, particularly when trying to persuade them to adopt new ways to handle something as basic and commonplace as water. Are they affordable? Are they easy to use and reliable? Are they scalable? There are too many examples of treatments that work in pilot projects with hands-on education and follow-up. The test is what happens when the support has been withdrawn. Will people return to their traditional practices? Barriers to adoption include timeworn habits, local norms, the smell and taste of treated water, and the lack of disposable income.

One of the more interesting debates concerns this last challenge of poverty. Is it more effective to provide POU treatments for free or to sell at a low price? One might assume that providing chlorine bottles for free, for example, would increase use since poverty will not prevent their purchase. Some research, though, suggests that those who purchase the kits are

more

likely to use them than those to whom the kits were simply given. When we get something for free, we tend to value it at the cost we paid—zero. Paying for the POU kits, by contrast, requires sacrifice and can create a sense of obligation to use them.

We know that the very poor are willing to pay for water, so it would seem reasonable to assume they would be willing to pay for POU treatments, as well, but this is not always the case. Paying for water is not the same as paying for chemicals or materials to treat

the water. As one researcher observed, “Some people are willing to pay for water quantity and for convenience, but in low-income countries many households will not pay for quality.”

There are some success stories that give reason for optimism, though. To take one example, the nongovernmental group PSI launched a product in Zambia called Clorin, basically a bottle of the disinfectant sodium hypochlorite. PSI developed a brand identity for Clorin, advertised on radio and TV spots, and distributed bottles for sale through traditional retail networks, health centers, and door-to-door vendors. A survey found impressive penetration—42 percent of households reported using Clorin. Thanks to aid from the U.S. Agency for International Development, the $0.34 cost of the bottle is subsidized and sold to the public for $0.12. In a country that ranks at the bottom of the United Nations Human Development Index, 164 out of 177, this level of use is no small achievement. It bears keeping in mind, however, that the typical adoption rate for chlorination POUs is much lower, closer to 5 to 10 percent. PSI’s initiative in Zambia is the greatest success story to date and offers important guidance for program design in other places.

Experts in development can argue about the relative merits of POU versus wells versus piped systems, but regardless of their approach, they all agree there is not enough money available to satisfy the demand for clean water in developing countries. Just as research on POU is challenging how we think about providing clean water, so, too, is the savvy creativity of one man challenging how we think about raising money to pay for clean water.

S

COTT

H

ARRISON STANDS ALONE AT THE BACK OF THE ROOM AS THE

students start to enter. With average height, close-cut hair, and a cropped beard, he’s well-dressed—a clean white textured shirt, designer blue jeans, leather shoes. The posters at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment say he’ll be talking about something called Charity: Water. Spotting the oldest person in the room, Harrison walks up to me and shakes my hand. “You’re a professor? Great. Tell me about the crowd.” As I describe the students’ back-grounds, he gives me his full attention and keeps saying, “Cool, cool.” A few minutes later, he walks to the front of the classroom, sits cross-legged on a desk, and in even tones starts talking.

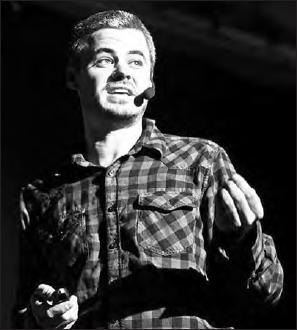

Scott Harrison, the founder of Charity: Water, speaking at an event in 2010

The room gets quiet as he shows photo after photo on the screen of Africans with enormous, grotesque tumors on their faces, most sticking out of their mouths. Harrison says he cried the first time he saw someone like this. The photos were taken by him in Liberia, when he was working aboard a hospital ship. He pauses, then starts to tell how he got there.