Early Dynastic Egypt (65 page)

In the absence of sufficient direct evidence for urbanism, scholars have often turned to the cemetery record (O’Connor 1972:80; Mortensen 1991). The location of a cemetery provides a reasonable, though by no means infallible, guide to the location of its accompanying settlement. Likewise, the size of a cemetery gives an indication of the size of settlement it served; the distribution of cemeteries has been used to reconstruct settlement patterns in various regions and at various periods (for example, Patch 1991; Seidlmayer 1996b: fig. 2). The conspectus of sites presented below draws upon both types of evidence for early urbanism: actual settlement material, most of it excavated in recent years, and Early Dynastic cemeteries for which the accompanying settlement has not yet been located or excavated.

Elephantine

Excavations on the island of Elephantine have revealed a continuous picture of urban development from Predynastic times. In the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods, the southern part of the island was divided into two, at least during the annual inundation. The settlement was located in the centre of the eastern island. The earliest habitation is now dated to the end of Naqada II, although a few isolated finds of earlier material out of context may indicate that the settlement had already begun at the beginning of Naqada II (Seidlmayer 1996b: 111). The arrangement of post-holes suggests an open settlement of

reed huts (cf. Leclant and Clerc 1994:430). The original extent of the Predynastic settlement is hard to gauge, since only limited areas have been excavated. The settlement may have been restricted to the northern part of the island, with a cemetery occupying the southern part; but it is also possible that the early village may have been much larger (Ziermann 1993:14–15; Seidlmayer 1996b: 111). The habitation area certainly extended eastwards towards the river bank, where it overlooked the main navigation route through the First Cataract area. The first mudbrick buildings were constructed on Elephantine at the very end of the Predynastic period (‘Dynasty 0’). Also at this time, industrial activity is attested: an oven with pieces of slag and traces of copper indicates that metalworking took place within the Predynastic settlement (Leclant and Clerc 1994:430).

The unification of Egypt at the end of the Predynastic period, accompanied by the imposition of a national government apparatus on the whole country, marked a decisive turning-point in the history of Elephantine. At the beginning of the First Dynasty, probably as the direct result of royal policy, a fortress was built on the island. Its strategic location was clearly designed to facilitate control of river traffic on the main river branch and the monitoring of activity in the area of cultivable land on the east bank of the Nile, the site of modern Aswan (Ziermann 1993:32, fig. 12; Seidlmayer 1996b: 112). Moreover, the prominence of the building would have emphasised to the local inhabitants and to passing traffic the omnipotence of the central, royal government. The fortress seems to have been built as part of a change in Egyptian policy towards Nubia, a policy which now became hostile and exploitative. Certainly, the construction did not benefit the local community nor did it take account of local sensibilities. Neither the existing settlement nor its shrine was included within the fortifications; the fortress was erected in the optimum location, with scant regard for the pre-existing buildings (Seidlmayer 1996b:112). When the fortification was strengthened and extended during the first half of the First Dynasty, the new wall ran so close to the forecourt of the local shrine that the shrine’s entrance had to be moved. As the result of a subsequent strengthening of the wall, the shrine forecourt had to be further reduced in size. The adverse impact of the fortification programme on the religious life of the local community paints a none-too- beneficent picture of the early state. The construction of the fortress on Elephantine illustrates the political dominance of the royal court after the unification of Egypt.

At the beginning of the Second Dynasty the settlement and shrine, which had previously been unenclosed, were fortified by means of a double wall connecting with the bastion of the fortress. This new town wall and the outer section of the fortifications were strengthened several times over the succeeding decades. Eventually, towards the end of the Second Dynasty, the expansion of the town led to the abandonment of the inner fortifications. This allowed the shrine to expand once again, regaining its former extent. Early in the Third Dynasty the walls of the old fortress, now surrounded by habitations, were levelled to form a continuous settlement area. None the less, a sealing of the governor of Elephantine from the reign of Sekhemkhet gives the town the determinative of a fortress, indicating that Elephantine was still viewed as a fortified settlement, at least by the central government who had built the fortifications in the first place (Pätznick, in Kaiser

et al.

1995:181; Seidlmayer 1996b: 113).

Until the middle of the Third Dynasty, settlement activity was confined to the eastern island. This was to change with the construction of a large complex of buildings on the northern granite ridge of the western island some time during or after the reign of

Netjerikhet (Seidlmayer 1996a, 1996b:120–4). The complex was enlarged and reinforced during a series of building phases. Late in the Third Dynasty, the courtyard area between the northern and southern granite ridges was filled and levelled, to support a new building. This development connected the original building complex on the northern ridge to the small step pyramid constructed on the southern ridge in the reign of Huni. The size and construction of the entire complex distinguish it from other contemporary buildings on Elephantine, and mark it out as an official, state-sponsored project (Seidlmayer 1996b: 120). This is confirmed by the associated finds, especially seal- impressions. Most significant is a sealing from a papyrus roll giving the title of the ‘royal seal-bearer of the

pr-nswt

’ from the reign of Sanakht. Even if this official was not himself based at Elephantine, the consultation of a court document on the island indicates that the Third Dynasty complex was associated with the royal domain. Other sealings indicate that food distribution operations were carried out on the site, confirmed by the vast quantities of bread-moulds and beer-jars recovered. The excavator concludes that the building was an administrative centre connected with the royal estate and notes that it was located ‘in a convenient place near the river and in the vicinity of the cultivable alluvial land accumulating to the north’ (Seidlmayer 1996b:121). It is quite likely that the complex on the eastern island at Elephantine was connected with a fundamental restructuring of the administration under the last king(s) of the Third Dynasty, a development which paved the way for the unprecedented harnessing of resources evident in the pyramid-building of the Fourth Dynasty. Elephantine is thus a key site for the rise of the Egyptian state and it bears witness to the changes which marked the transition from the Early Dynastic period to the Old Kingdom.

Elkab

The significance of Elkab from the period of state formation onwards is demonstrated both archaeologically and iconographically: by the numerous graves of the late Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods; and by the adoption, at the very beginning of the Early Dynastic period, of the local deity (Nekhbet) as the tutelary goddess of Upper Egypt and, later, as an element of the royal titulary (Vandersleyen 1971:35).

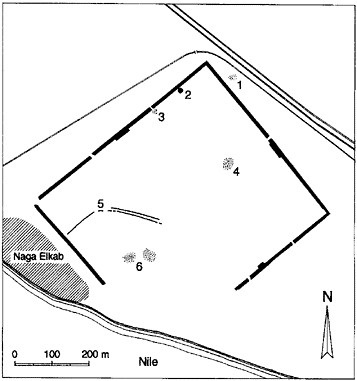

Excavations at the turn of the century (Quibell 1898b; Sayce and Clarke 1905; Clarke 1921), and by successive Belgian missions since the 1940s (Vermeersch 1970; Vandersleyen 1971; Huyge 1984; Hendrickx and Huyge 1989; Hendrickx 1993) have revealed several settlement and cemetery areas (Figure 9.1). The ancient site of Elkab is mostly contained within a large rectangular enclosure wall of mudbrick, named the Great Wall by the early excavators. Within this outer enclosure are situated a smaller, walled temple enclosure and the partial remains of a curved, double wall (Hendrickx and Huyge 1989: pl. II) which may have enclosed the early town (Vermeersch 1970:32–3). The double wall must originally have demarcated a roughly circular area, conforming to the hieroglyph for ‘town’. Because of the northward movement of the river channel since ancient times, the south-western half of the ancient town has been eroded and is now lost. However, there is some evidence that the town extended westwards beyond the limits of the Great Wall. At the end of the nineteenth century, there was ‘ample evidence of habitations, outside and west-ward of the western line of the Great Walls’ (Clarke 1921:56). A few years later, a section of the curved double wall and large amounts of

ancient pottery could be seen exposed in the Nile bank (Sayce and Clarke 1905:263; Clarke 1921:56).

The location of the large, late Predynastic (Naqada III) cemetery (Hendrickx 1993)— which would have lain outside the settlement—indicates that the early town lay in the south-west corner of the later, rectangular enclosure wall. The limited amount of archaeological material excavated within the curved double walls seems to confirm this area as the heart of the ancient town. The only architectural evidence consists of small mudbrick constructions. The floor of one chamber was covered with sherds of Early Dynastic pottery, and a large jar had been sunk into the ground. Numerous flint objects found here provide further evidence of early occupation (Vermeersch 1970). Similar material (pottery, flints, fragments of stone vessels), some of it dating back to the Predynastic period, was excavated at the beginning of the twentieth century in a trench to the east of the temples (Sayce and Clarke 1905:259). This location would correspond to the edge of the probable ancient town-site. Unfortunately, more extensive evidence of the early occupation at Elkab is unlikely to be forthcoming, since it appears that much of the site was thoroughly

Figure 9.1

Elkab. Confirmed Early Dynastic features within and around the later rectangular town wall (after Hendrickx and Huyge

1989:10–14, pl. II). Key: 1 possible location of a Predynastic cemetery; 2 building of Khasekhemwy; 3 Early Dynastic tombs; 4 late Predynastic cemetery; 5 double wall, enclosing the early town; 6 excavated areas of the Early Dynastic town.

levelled at the end of the Early Dynastic period or perhaps during the Old Kingdom, for the construction or reconstruction of the temple compound (Vermeersch 1970:33; Vandersleyen 1971:35). Moreover, a substantial town mound within the curved double walls, noted in an early century account, was removed by sebakh diggers in the nineteenth century (Clarke 1921:56–61). On the spot where the temple now stands, excavations failed to reveal any domestic settlement material later than the Early Dynastic period. This fact suggests that the site was regarded as holy from an early period (Sayce and Clarke 1905:262). However, domestic vessels (‘ash-jars’) of Predynastic date indicate that the site was probably not sanctified until after the formation of the Egyptian state (Sayce and Clarke 1905:262–3).

There is only limited datable evidence of Early Dynastic activity in the Elkab region. One of the stairway tombs (No. 6) excavated at the end of the nineteenth century just outside the north-western side of the Great Wall contained a rectangular stone palette, characteristic of the early First Dynasty (Quibell 1898). From the end of the First Dynasty there are two rock-cut inscriptions of Qaa (Huyge 1984). Both show the royal

serekh

facing a figure of the local goddess Nekhbet. One inscription is carved on a rock in the Wadi Hellal, the other at a site some 12 kilometres downstream. A small steatite plaque bearing the name of the Second Dynasty king Nebra was reported to have come from another of the stairway tombs (No. 2) (Quibell 1898b). The existence of a stone building of the late Second Dynasty, just inside the northern corner of the Great Wall, is indicated by a number of granite blocks, one of which (now lost) bore the name of Khasekhemwy.

There are several cemeteries of the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods at Elkab. The principal Predynastic cemetery, dating to the period of state formation (Naqada III), lies within the Great Wall and seems to have formed part of a more extensive cemetery, the original extent of which is difficult to establish (Hendrickx and Huyge 1989:12 (24); Hendrickx 1993). Tombs of the Early Dynastic period are somewhat better represented at Elkab. In particular, the existence of several high-status burials indicates the early importance of the town. A group of small mastabas dating to the Second and Third Dynasties was excavated adjacent to the inside north-western edge of the Great Wall, close to the granite blocks of Khasekhemwy (Sayce and Clarke 1905:239; Hendrickx and Huyge 1989:12). Although thoroughly plundered, the burials seem to have belonged to a larger cemetery comprising also some early Old Kingdom mastabas (Sayce and Clarke 1905:242). There are sketchy reports of further Early Dynastic graves having been uncovered in the elevated part of the enclosure north of the temple; and there were apparently a few early burials within the mainly Middle Kingdom cemetery to the east of the temple area (Sayce and Clarke 1905:246).

Other books

Minor Adjustments by Rachael Renee Anderson

The Price Of Darkness by Hurley, Graham

The Hermetic Millennia by John C. Wright

Twin Dangers by Megan Atwood

Read Bottom Up by Neel Shah

Red Right Hand by Levi Black

Matter of Trust by Sydney Bauer

Never Trust a Rogue by Olivia Drake

Batman 1 - Batman by Craig Shaw Gardner

War Stories III by Oliver L. North