Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 (15 page)

Read Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 Online

Authors: Christine Alexander,Mason Kunze

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027100

Hans Roth with his comrades in front of a Sd.Kfz. 232 Schwerer Panzerspähwagen. (Photo courtesy Christine Alexander and Mason Kunze)

JOURNAL II

MARCH TO THE EAST AND THE WINTER OF 1941–42

Editors’ Note:

Unknown to Hans Roth, while his infantry division had waged a bloody confrontational combat before Kiev, a huge debate had raged among the German high command that would have profound consequences for Operation Barbarossa as well as the entire course of World War II.

By early August von Kleist’s First Panzer Group of Army Group South had advanced 150km east of Kiev along the lower Dniepr, while Guderian’s Second Panzer Group of Army Group Center had reached a similar point to the north. Budenny’s million-man Southwest Front now looked like a salient, capable of being bitten off should the two panzer groups advance toward each other behind the Soviet concentration. However, to strip Guderian from Army Group Center would mean calling a temporary halt to its drive on Moscow.

Hitler was the main champion of eliminating the Kiev salient, since he believed that by erasing the main Soviet grouping in the south it would gain him the Donetz industrial region as well as the Caucasus oil fields. He may have also had an instinctive reluctance to follow the path of Napoleon, who had marched straight for the Russian capital, only to find himself holding a worthless prize with the true strength of Russia swarming on his flanks.

The chief of the German General Staff, as well as all the generals of Army Group Center, argued that Moscow had to remain the

Schwerpunkt

of the offensive, since for political, economic, and communications reasons it was far more important in 1941 than it had been in 1812, and that Stalin’s war effort could not survive its loss.

Hitler won the argument, and in late August the Second Panzer Group peeled off from Army Group Center to drive south. A few days later the First Panzer Group drove north, and on September 14 the two forces met at Romny, east of Kiev. When German tanks marked with “G” (Guderian) met tanks marked with “K” (Kleist) it meant that Budenny’s Southwest Front holding the capital of the Ukraine was doomed. It turned out to be the largest single victory in the history of land warfare, with 665,000 prisoners taken, and the entire south of the Soviet Union apparently laid open for further advances.

In his contemporaneous journal Hans Roth appears unaware of the strategic machinations, only seeing that Soviet resistance during his final attack on Kiev (his division was one of the first to enter the city) seemed to have evaporated. In fact, Budenny had begun to evacuate the salient as soon as he learned of the movements of the panzer groups behind him, but Stalin had countermanded his orders and demanded that he hold fast. Budenny was relieved of command and his successor was killed in the pocket.

Sixth Army’s von Reichenau, though doubtless an excellent commander, was also the most “Nazified” of all the senior German generals in the East at this time, and issued orders to his troops to be ruthless with the civilian population. During his time in Kiev, Roth’s journal describes him witnessing, with horror, an

Einsatzkommando

action, which may well have been Babi Yar.

After the reduction of Kiev, Army Group Center retrieved its Second Panzer Group (the Third had been dispatched north to assist around Leningrad) and resumed its drive on Moscow in early October. At first huge victories were won, at Vyazma and Bryansk, but then the Soviets were able to call on their strongest ally—which Roth well describes in person—General Winter.

Now deep into Russia across a front of a thousand miles, the Germans found the late-autumn roads behind them collapsing into mud. Supplies and ammunition could no longer reach the frontline troops. When the ground froze the vehicles could move again, but then it turned out to be the earliest and most severe winter in memory, rendering German

Soldaten

—still in their summer uniforms—almost helpless against frostbite, with many of their weapons useless in the bitter cold. The worst development was that the Soviets appeared to possess unlimited reserves, including entire divisions of Siberian troops, well clothed and equipped for winter warfare. Stalin commenced a counteroffensive all along the front.

During this period when German troops were obviously at the end of their tether, Hitler sacked a number of generals who demanded to withdraw to more defensible lines. Among these were Guderian and von Rundstedt, commander of Army Group South, the latter replaced by von Reichenau, Hitler’s most fanatic general, though he quickly realized that his predecessor had been correct. (Reichenau himself died of a heart attack within weeks.)

Hans Roth’s

Panzerjäger

unit appears to act as a “fire brigade” during the winter of 1941–42, dispatched from crisis to crises, though his main battles take place at Oboyan (Obojan), near the crucial rail link between Kursk and Kharkov (Charkow) at the apex of Sixth Army’s advance.

Somehow surviving the winter, he seems both mystified and relieved when fresh German reinforcements come pouring into the front with the advent of spring, though he concludes this journal with simply wishing to see his wife and young child again.

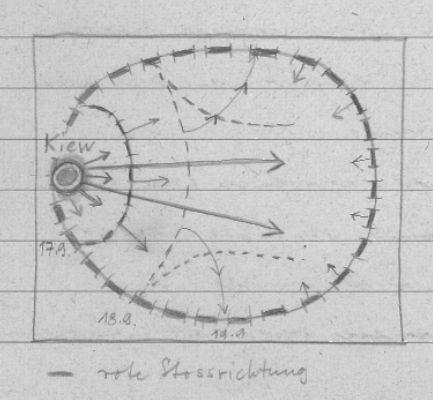

Hans Roth’s depiction of the Kiev pocket and the Red Army’s attempts to break through the German encirclement, September 17–19, 1941.

23 September:

Heavy fighting is to our rear. Early on September 19 we penetrated the heavily armed outer ring of the city. The enemy, by far not as strong as we had assumed, was defeated in a bloody, close combat, and by 0900 hours we had already reached the western part of the city. The Reds have quit their attempts at heavy street fighting. At the same time, strong assault parties attacked the citadel from the direction of Lysa-Hora, and by 1100 hours Nazi swastikas were raised there.

By noon we are in the center of the city, no shots are heard; the wide streets and squares are abandoned. It is eerie. The silence is making us nervous, for it is hardly believable that such a large city has fallen into our hands in such a short amount of time. Is this a ruse? Is the city a trap covered in mines? Are we standing on a volcano?

These are the questions that everyone is currently asking. Today we have an answer to all of these questions. In order to lure the occupying armies out of the city, which was to be spared at all costs from combat, a German offensive was simulated east of Kiev back on September 17, with huge artillery preparations. Budenny issued orders for a devastating counteroffensive, which in doing so removed troops from the wellequipped defense circle, and in turn nearly completely exposed the city. Approximately 120km east of the thin German line, the location of the mock operation, is the supposed outflanking army. Made drunk by victory—as they hardly encountered any resistance—Budenny’s troops chase the “fleeing” Germans. They advance farther and farther east, and by September 19, are many, many kilometers away from Kiev. At this moment, the fate of several hundred thousand of Budenny’s Bolsheviks is sealed. What irony of fate! Budenny, who up until now, intoxicated from his victory, believes that he is herding before him a panic-stricken, fleeing German army, pushes with tremendous pressure, though only into nothingness, for the enemy has vanished overnight. Only against one flank corps is there a minor exchange. Regardless, he believes he has cut the enemy to pieces (bad lines of communication were perhaps the main reason for his devastating defeat).

An irony of fate: in these days of victory celebrations, Stalin, who believes Budenny to still be in Kiev, gives orders to prepare the city for a winter defensive. And then, that afternoon, it hits HQ like the crack of a whip: Kiev is in German hands. Lost, everything lost! The drama has begun!

What does this western defense line, which Budenny depended upon just like the French did with the Maginot Line, look like? It’s not a common line of bunkers; no, it is a collection of diabolic resources, which can only be conceived by the brain of a paranoiac. I will try and describe some of these horrific death zones that we passed through while intensely fighting on September 17, 18, and 19:

To the rear of Gatnoje, there are fields of cooperatives, vast vegetable farms. They lie there harmlessly in the sun. Who would believe that hiding among those plants is the most horrific death: a high voltage current! Atop the vegetation is a webbing of fine caliber wire the length of several kilometers. This rests on thin, isolated metal poles, which are all painted green; a deadly net of high voltage current, which is run by a power plant in a bunker. It is so well camouflaged that we recognize it unfortunately much too late, only after the continued accumulation of losses.

Then there are the devil’s ditches, lined up in great depth, several hundred meters long. They are mined, and when a single land mine is tripped, entire fields, which are connected underground by detonation channels, explode. At the same time, water pipes explode and rapidly flood the area two meters deep.

There are even a few more goodies that happen to be just lying on the ground, seemingly random objects that are interesting to every soldier: watches, packs of cigarettes, pieces of soap, etc. Each of these objects is connected to a hidden detonator. If the soldier picks any of these objects up, he starts the ignition and detonates a mine or an entire minefield.

In this category also belong well-hidden trip wires, which cause contact mines to explode. These monsters jump up 3/4 of a meter and explode, showering burning oil everywhere. There are other areas where hidden among trip wires are thousands of knife-sharp steel spikes, which are poisoned and cause the injured to die a horrible death ten minutes later. All of the defensive belts are littered with automatic flame-throwers, which are activated by pressure.

Well—just imagine, among all these devilish things there are still the normal battle installations: two-story bunkers, automatic weapons stands, ditches, tank ditches, kilometers of barbed wire, tank barriers, in addition to the average mined streets and paths. Add to that infantry mines, booby traps, ban mines, vehicle mines. And now, just imagine this whole hellish apparatus during combat; this is their defense against our attack.