Eat and Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon Greatness (10 page)

Read Eat and Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon Greatness Online

Authors: Scott Jurek,Steve Friedman

Tags: #Diets, #Running & Jogging, #Health & Fitness, #Sports & Recreation

Now, waiting to meet me at 50 miles in Chilao Campground, he was screaming at me again. But this time it wasn’t “You’re a pussy, Jurker,” or “C’mon, you Polack,” or any of Dust Ball’s other charming greetings.

It was Spanish.

I looked over my shoulder, finally realizing who he was yelling at. There was a knot of sinewy, coffee-colored men with ink black hair wearing loose shirts, long things that looked like skirts, and huarache sandals made from discarded tires. They looked to be in their forties. I had first heard about them from a friend from New York, Jose Camacho, whom I had worked with at the VA Hospital in Albuquerque during one of my PT internships. He had a quote taped to his locker: “When you run on the earth and with the earth, you can run forever.”

Anyone who had competed in more than one ultrarace in the United States had probably heard of these men. They were the Tarahumara Indians of Mexico’s Copper Canyon, an ancient people who supposedly could run hundreds of miles without even breaking a sweat. As the story went (and as the bestseller

Born to Run

would later document), they didn’t talk much, subsisted on a mostly plant-based diet, and grew up running the way American kids grew up watching television or playing video games. Dusty and I had seen them at the starting line, smoking cigarettes (or joints; we weren’t sure). They stood apart from everyone else, neither smiling nor frowning. While other runners stretched and warmed up, they just stood there. Some of their skirts were obviously put together recently. One of them had fashioned his from a sheet printed with Big Bird.

A runner named Ben Hian, who had won the race three of the past four years and was one of the best 100-milers in the country, had sidled up to Dusty and me. Ben was a recovering drug addict who loved tattoos: men crawling out of coffins, skulls, that sort of thing. His entire upper body was covered in ink. He wore a Mohawk, loved Ozzy Osbourne, and ran a business where he took tarantulas, snakes, and lizards to libraries and Girl Scout troops, among other places. Oh, and he taught preschool.

“Those guys don’t even get warmed up till 100 miles, and they stop at the top of each ridge and all smoke something. Peyote, marijuana, I’m not sure what,” Ben said with a grin. Or was it a smirk? He stretched a little, flexed his tattoos.

Was he screwing with us or was he serious? I didn’t know.

“Yeah, right,” Dusty had replied. “That is total bullshit.” Then he told Ben that I was going to beat his ass. Good old Dusty.

But now he was yelling Spanish at them. (Later I learned it was something along the lines of “Fuck you, you slow Big Bird–wearing idiots.”) I glanced back again and did a double-take. They really did seem to be floating up the mountain with no effort.

Had

they been smoking something? If so, I wouldn’t have minded some.

Before the race, I had confessed my concerns about running 100 miles, and Dusty had told me not to be a pussy, that “this is just a 50-mile race, then another 50-mile race after. And you get stronger the longer you run.”

As I suspected, Ben Hian was my main competition. The other guy I knew I had to beat in order to win was Tommy Nielson, aka Tough Tommy. Tommy was known for his grit and a particular trick. If he was pursuing someone at night, he would switch off his headlamp until he was next to his quarry, then flash it on and move into a near sprint. It had demoralized runners who thought they had the lead, only to be passed before they knew they were even being chased.

I chased Ben Hian the first 50 miles of the course, and the Tarahumara chased us. Every steep incline, I’d gain ground on Ben, but the Tarahumara would

gulp

ground on me. How were they doing that floating thing? Every downhill, Ben and I would crash over rocks and bushes, and the Tarahumara would gingerly pick their way. I suspected it was the huaraches. But I also knew if they ever figured out the trick to descending in a race, they’d be invincible.

As the miles added up—Dusty joined me at mile 50 to pace me the rest of the way—I kept waiting to seize with cramps or for my knees to blow up or to look down and see I had swollen hands. I had never run so far, and I wasn’t at all sure I could take the distance.

The Tarahumara chased me all the way to mile 70, gliding up mountains, tiptoeing down. After that, they slowed.

At 90 miles, it was the middle of the night, and Dusty and I saw lights behind us and ahead. That’s when we decided to pull a Tough Tommy, and we shut off our lamps. Evidently, though, Tommy pulled a Tommy, too, because suddenly the light chasing us had disappeared. Ben also pulled a Tommy. We ran that way until the end, chasing invisible Ben, running from invisible Tommy. It was an amazing feeling, and somehow I didn’t feel my tired legs and sore feet. I ran as if I had run only 10 miles instead of 90. We finished with 10 minutes between each of us.

When we got to the finish line, I had a second-place finish. I had defeated the members of a legendary tribe and almost caught the Man of Tattoos. I had almost won my first 100-miler.

Now I knew I could run this distance. I knew I could win, too. But few others knew it.

It was my little secret.

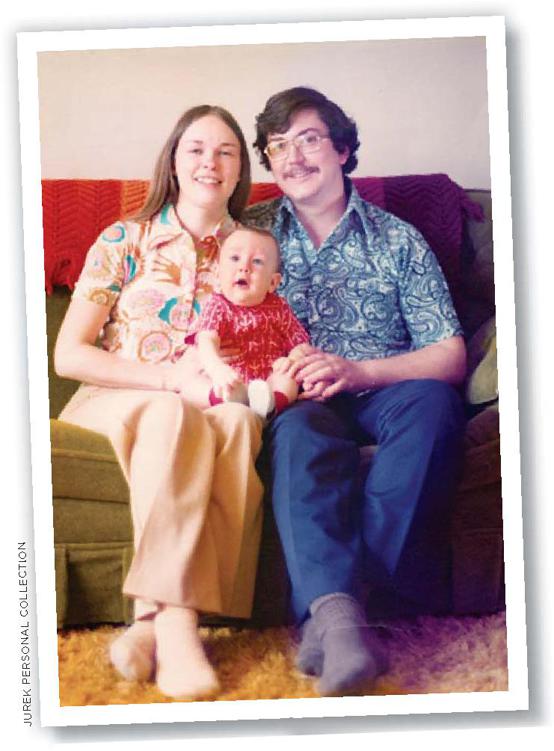

My mom, Lynn, taught me to cook. My dad, Gordy, taught me to hunt and fish. Though I suspect they didn't know it at the time, they both taught me, in word and deed, to endure.

My mom, Lynn, taught me to cook. My dad, Gordy, taught me to hunt and fish. Though I suspect they didn't know it at the time, they both taught me, in word and deed, to endure.

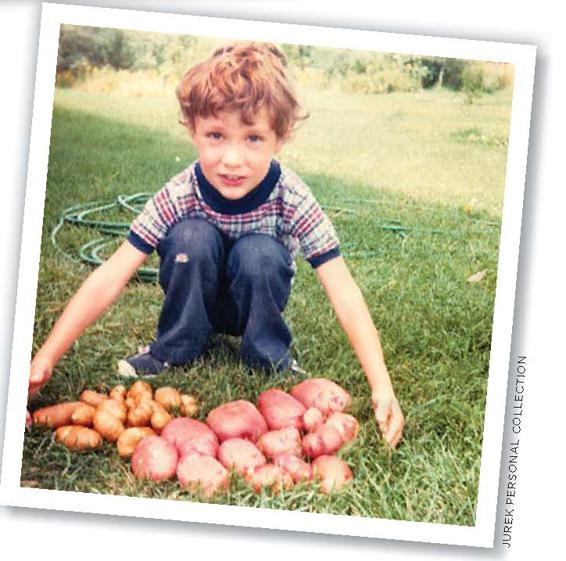

I was four years old and had just finished digging potatoes with my dad. I already knew that the best food in the world was the food you grew yourself.

I was four years old and had just finished digging potatoes with my dad. I already knew that the best food in the world was the food you grew yourself.

In 1984, finishing (but not winning) the Park Point Kids' Mile along the shores of Lake Superior, I discovered two things: I wasn't particularly fast, but I seemed to get stronger as the race got longer.

In 1984, finishing (but not winning) the Park Point Kids' Mile along the shores of Lake Superior, I discovered two things: I wasn't particularly fast, but I seemed to get stronger as the race got longer.

As an 18-year-old high school senior, I started placing near the top in open ski events. Skiing was my passion. Running was a means to stay in shape for that.

As an 18-year-old high school senior, I started placing near the top in open ski events. Skiing was my passion. Running was a means to stay in shape for that.

"Hippie Dan" Proctor was a local running legend when I met him in 1992, and he taught me about the joys of living a simple, attentive life. When I returned to Duluth in 2010, to visit him in his solar-powered house, I found he hadn't changed much.

"Hippie Dan" Proctor was a local running legend when I met him in 1992, and he taught me about the joys of living a simple, attentive life. When I returned to Duluth in 2010, to visit him in his solar-powered house, I found he hadn't changed much.

The first time I beat my best friend and running mentor, Dusty Olson, was the 1994 Minnesota Voyaguer 50-miler. When I finished, I fell to the ground, convinced this was the hardest thing I would ever do. If only I had known.

The first time I beat my best friend and running mentor, Dusty Olson, was the 1994 Minnesota Voyaguer 50-miler. When I finished, I fell to the ground, convinced this was the hardest thing I would ever do. If only I had known.

I heard about the Western States 100 the way Little Leaguers hear about Babe Ruth. When I first ran it, in 1999, I decided if I didn't win, it wasn't going to be because I didn't give everything I had.

I heard about the Western States 100 the way Little Leaguers hear about Babe Ruth. When I first ran it, in 1999, I decided if I didn't win, it wasn't going to be because I didn't give everything I had.

My dog taught me a lot about running. For four years, Tonto trained with me on the mountain trails of Washington and Northern California, preparing for the Western States 100.

My dog taught me a lot about running. For four years, Tonto trained with me on the mountain trails of Washington and Northern California, preparing for the Western States 100.