Edie (7 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

The Sedgwicks (

left to right

): Halla, Babbo, Francis, May, and Minturn

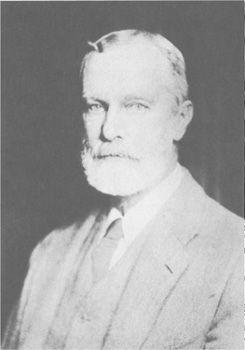

MINTURN SEDGWICK

Francis was concentrating on Fine Arts at Harvard, but what he really wanted to be was a tycoon. When he won a Clarence Dillon scholarship, Babbo, who was not in the least worldly-wise, told his son, “Now that you’ve won this scholarship, why don’t you go down to New York and call on the great man? I’m sure none of his other scholars wI’ll ever come near him.” So Francis went to see Mr. Dillon and made a great hit with him. Dillon asked him what he was concentrating on. “Fine Arts and Finance,” said Francis. Dillon apparently said, “Splendid. That’s just what I did in college.” Then Dillon asked him what he expected to do when he’d graduated. Francis told him that he planned to study at Trinity College in Cambridge for a year. Then he said, “After that I’d like a year of banking experience in Europe.”

Clarence Dillon wrote several letters of introduction for Francis. So for the summer of 1927 he was a sort of an honored aide representing the powerful and brilliant Clarence Dillon throughout European banking circles, starting in Berlin with the Diskont Gesellschaft. In Paris that year Francis received a cable from Dillon saying, “I’m taking a few friends on a Mediterranean trip. WI’ll you join us in Gibraltar?” There I was working away at a little branch bank in Boston, while Francis seemed already well on his way to becoming an international tycoon.

LILY MAYNARD

The cruise ship was called the

Baltic.

I was about nineteen or twenty, and my family thought I was up to no good in New York. I was idle, like most of my generation. And they didn’t like the young man I was seeing. I was to be chaperoned on the trip by Mrs. Rogers Winthrop, who had her eighteen-year-old daughter, Alice, along with her. Also on the trip were Charles Dana Gibson, the celebrated illustrator, and his wife, who was the original Gibson Girl. I remember the older ladies on the trip saying to Mr. Dillon about Francis: “Let’s see the Adonis.”

I had a bit of a flirt with Francis—a modest, chaste kiss in the moonlight. He was a very handsome man, quite vain, a rather faddish person who drank two glasses of milk a day—a kind of a health maniac. He was enormously clean; he smelt good.

Mr. Dillon had expected to like Francis, but I had a feeling that he did not take to him. He was being tried out as an assistant, a courier, a private secretary; he would get tickets, pick up baggage.

After the trip I saw Francis in Paris and then in Cambridge. He was very intense with his emotions. He fantasized quite a bit. I think he

was a man who saw himself in pictures of his imagination and dreams. He got rather intense about marriage. I found him a very attractive beau . . . a very pleasant Cicerone . . . but I was not prepared to get married. I told him in Cambridge it was all over, and he looked sad punting on the Cam River.

MINTURN SEDGWICK

Soon after the cruise Francis went to London to work in the investment banking firm of Lazard Frères. Again he played and worked very hard until one morning he suddenly collapsed to the floor. We knew nothing about it until about two or three weeks later, when a cable arrived from Francis saying: “The reason I haven’t written was they thought I was going to die, and there was no sense in telling you that. But what they thought was a heart attack was a nervous breakdown.” Of course, that was the end as far as his financial possibilities with the Dillon empire were concerned.

After he’d been in a nursing home in England, his doctor said: Is there some pleasant place near here where you can stay quietly for a month before going home?” Francis remembered a close friend and classmate from Groton, Charles de Forest, whose father had taken a summer place called Tilney, a manor house in the English countryside. The de Forests said they would be glad to have him. So he went, and that’s where he met Charlie’s younger sister, Alice.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My parents actually met for the first time years earlier, when my father was at the Cate School. My mother had gone out to Santa Barbara on a trip with her parents, and my uncle Charlie de Forest had suggested they look up my father. My father was about sixteen years old and very handsome, my mother was twelve. When my mother saw him, she fell in love with him then and there for life. She had to wait about eight years. My grandmother told me that my mother knew what she wanted and no one could talk her out of it.

My mother grew up on Long Island on an enormous place called Nethermuir, which had been in the family since 1866. It was a hundred and fifty acres of wild laurel, woods, and lawns that went to the edge of the water, with a view of Long Island Sound. My grandfather Henry de Forest was an amateur landscape gardener, and I remember as a child walking around the grounds with him. He wore dark gray or brown tweed suits with a waistcoat, and he always had a hat on and carried a walking stick. I’d see the gardeners tipping their hats to him.

GEORGE PLIMPTON

When I was a boy I used to see the de Forest estate across Cold Spring Harbor from the Beach Club. There was a boathouse with a dock on the water, and the big white house up the hill, with lawns and formal gardens.

I used to wonder what went on up there—very grand doings, I always supposed. One thing I knew about them was that they once had a private railway car. The old man must have cut quite a figure—he came from a distinguished New York family. He was a director of the Southern Pacific Railway, which put him at the right hand of E. H. Harriman, the railroad tycoon, who was one of the most powerful men around. So the de Forests in their heyday could have lived like princes, but apparently they never did.

In a way, the community is characterized by the Cold Spring Harbor Beach Club. it’s quite an institution. To begin with, it has no beach. The clubhouse is a simple, shacklike structure. No liquor is served. My father told me that it used to have a rule that if you were a man, you had to wear a top to your bathing suit, which was due largely to Colonel Henry L. Stimson, the onetime Secretary of War and one of the great figures of Cold Spring Harbor, who had a slightly hairy chest which he didn’t want to display. A number of distinguished figures turned up there—John Foster Dulles, Marshall Field, Allan Dulles (I can remember him playing tennis invariably under a wide-brimmed straw hat), Arthur Ballantine, and, of course, the de Forests. My father used to say that the general ambience of Cold Spring Harbor was one of a restrained Presbyterianism marked by austerity, virtually no excesses of any sort, with nobody throwing his weight around, a very simple community which attracted the best because it made a point of not being at all flamboyant or like a Gold Coast.

SAUCIE SEDGWICE

My grandfather de Forest must have been a man of strong opinions, but I heard of them only through my grandmother. She told me once that she and Grandpa had voted for Franklin Roosevelt because “Grandpa said that any child of Sarah and Jimmy’s was bound to be a good governor.” But then, she said, “Franklin was very impolite to your grandfather. There was an anti-trust hearing, and not only was Franklin on the other side, but he didn’t even take off his hat to your grandfather when he came into court I Grandpa never voted for him again.”

My grandfather didn’t marry until he was forty-two. Then he chose a young woman from St. Paul, Minnesota, named Julia Gilman Noyes. She was staying near Cold Spring Harbor, visiting her friend May Tiffany, the daughter of Louis Tiffany, whose family lived in Laurel Hollow next to the de Forests. My grandmother was twenty-three then, and while she belonged to what she would have called a “respectable” Connecticut family, I think she felt at a disadvantage coming from St. Paul. Her father had moved there for reasons of health in the 1860s, and I suppose he prospered, because Grandma was told as a young girl that she could afford a cook even if she married a clergyman—she would have a dowry of a quarter of a million dollars. So perhaps when she landed Henry de Forest she may have been a bit provincial. But she soon learned. She loved expensive clothes; she loved respectability, but mainly she must have loved being grand. She told me once that her bare feet never touched the floor because her French maid always left a pair of slippers at her bedside.

Henry de Forest (Edie’s maternal grandfather)

Julia Noyes, Edie’s maternal grandmother, with her mother

No question, my grandmother became a great lady in everybody’s eyes. You cannot imagine the stately progression of her day: interviewing the cook in the bedroom in the morning, reading the mail at her desk before lunch, followed by sherry, followed by lunch, then a little walk around the garden, changing to a long dress in the afternoon, pouring tea at five even if she was by herself. And no day varied from the day before or from the day after. She did exquisite needlework and embroidery; she read a lot of history and kept charts of European royalty in big notebooks.

My grandparents had four children. My mother, Alice Delano de Forest, was lie youngest, born in 1908 when her father was fifty-three. There were two older brothers and an older sister. In 1913 the eldest son died suddenly of a brain tumor just before he was thirteen years old. My grandmother went into mourning and put away the wardrobe she had bought each year on trips abroad. My mother was only five at the time, but the message of terror and suffering must have gotten through to her. She remained closest to her other brother, Uncle Charlie, who she felt was the most important person in her life, and she worshiped her father—she called him Fuzzy because of his beard.

My mother was the darling of her father—there was a strong bond between them. She was very much a tomboy. And her relationship with him was very close—lots of hugging and sitting in his lap. There was definitely competition between my mother and grandmother for Grandfather de Forest.

I’ve seen pictures of my mother taken that summer of 1928 at Tilney when she and my father met again. She wore tweed skirts, wool sweaters, and brogues—shoes that look as if she was about to set off on a round of golf. She has a shy, happy look in those pictures—they show her warm nature. Although I have never known whether my father shared his mental horrors with her, I’m sure he confided in her and that he trusted her utterly. I imagine that she may have felt that only she understood him, and that her faith would restore him.

The New York Times

, Thursday, May 9, 1929

Social News

OLD FAMILIES SEE MISS DE FOREST WED

Younger Daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Henry W. de Forest Marries Francis M. Sedgwick