Edie (10 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

It was an unhappy time. My mother’s looks had changed. She’d had a mastoid operation in her late twenties, and in the course of it the doctor cut a nerve. At first the right half of her face was paralyzed. It sagged and her smile was very lopsided. Her eye rolled uncontrolably and she had muscle spasms. I remember trying to imitate it, to the horror of my governess. I didn’t think it was ugly, but it was pronounced, and it must have driven her in on herself terrifically. I never once heard her complain or saw her give in to it.

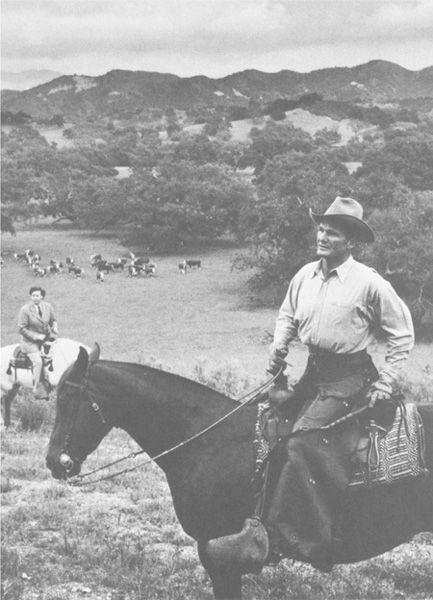

Francis and Alice Sedgwick at Corral de Quati

The symptoms abated eventually, but my mother wasn’t beautiful any more. She always looked nice, but she was heavy from so many pregnancies, and she wore her hair in a tight little permanent.

Then there was a feeling at this stage of being pinched for money, of cutting corners. We children were dressed in hand-me-downs from our Eastern cousins, and we got very little for Christmas or birthdays.

The only reason my parents had been able to buy Corral de Quad was because my grandfather had died. They couldn’t have bought it before; now they invested so much of my mother’s inheritance in land that they were land poor. Before my grandfather died, he had lost fifty or sixty million dollars in the Wall Street crash. He willed half of his remaining money—several million dollars—to my grandmother, the other half to be divided equally between my mother and her older sister, Molly. My grandmother changed the wI’ll so that she, my mother, and Aunt Molly got equal amounts. But my father always complained to Uncle Minturn that his father-in-law had died penniless, which is ridiculous but shows how disappointed my father was that there were no longer private railroad cars or rented castles in England.

Owning a three-thousand-acre ranch was very important to my father. Because Babbo was a historian and never made much money, his family had always lived in borrowed houses, rented houses, little houses on big places. They had always been one step behind—always the poor relations. And my father wanted to live in the

big

house. He tried to buy the Old House in Stockbridge but the Sedgwick family wouldn’t sell it to him because they wanted to make a trust and have the house belong to the entire family. My father wanted the big house to himself.

After my grandfather de Forest’s death, particularly after we moved to Corral de Quad, my father began to behave differently: he was only boisterous with guests. Around the family he was icy and remote. My mother became cautious and reserved. At the same time, they began opening up to different types of friends—ranchers from around the Santa Ynez Valley, artists from Santa Barbara, people here and there that they took a fancy to. They began adopting young couples. Often my father would have an affair with the wife. So by the time my youngest sisters, Edie and Suky, were born, my father was definitely fooling around.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My mother had a difficult time with the births of her last children, but she kept getting pregnant anyway. I know my parents expected to have another boy. My mother turned out to be allergic to anesthetics, and when Edie was born she nearly died. It was very close. It affected everyone. Babbo used to say that he had told the Lord in words of one syllable what he thought of his “baby system.” My father was afraid when my mother was having those last babies that she was going to die, but on the other hand he had begun to like the idea of producing a spectacular number of children. As for my mother, I have no idea why she went on having children when it was so dangerous for her.

Edie was born at the Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara, April 20, 1943, the first child after my parents moved permanently to California. She was the seventh of the eight of us, and named for our father’s favorite aunt, Edith Minturn Stokes.

Edie was very little when Jane Wilson became her nurse. She was a strong, kind, straightforward person—she was strict, but you knew where you stood with her; nothing was devious. She loved those children in her way, and she interceded for them and invested quite a lot in them, I think.

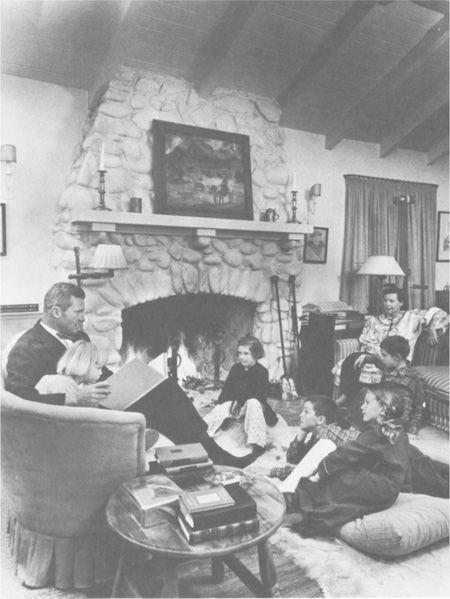

The Sedgwick family at home, Corral de Quati

(clockwise):

Suky with Francis, Edie, Alice, Jonathan, Kate, and Minty

JANE WILSON

Edie was six months old when I took over. I had Kate and Edie and then Suky. I started to toilet-train Edie right away. She did everything in her diapers, and I wouldn’t have that. She had to sit until she did it. That’s the one thing I was always fussy about with all my children. Suky was only two weeks old when she came home, and I started

her

on the potty. You hold them up, the little potty on your lap, and then patiently wait. It doesn’t take them long to know what they’re there for. I never spanked Edie or any of them. Jonathan used to claim he had nightmares. He was about seven. I told him, “Is this what you want?” and I showed him a hairbrush. He never had another nightmare.

I’d take Edie over to the main house from the cottage we lived in to say good morning to her parents. She’d refuse. Edie knew she’d have to sit until she’d said good morning, but she was determined not to give in and she would just stare at you. She never cried, that was the last thing she’d ever do.

Edie had a wI’ll of her own. It was born in her. The parents spoilt her. Anything Edie wanted to do was fine with her parents, but not with me. She had to mind and she had to eat everything on her plate, and I wouldn’t allow her to push Suky around.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

I was almost twelve when Edie was born, and most of the time when she was growing up I was away at school. So were Bobby and Pamela. Even when we were home we didn’t see much of the younger children in those early years.

Right after the war, “the three little girls,” as Kate, Edie, and Suky were always called, lived like poor kids, dressed in hand-me-down pale green overalls and jackets and scuffed brown shoes. They looked like little Maoists playing in the sandpit.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

Birthdays were really strange. The joy was out of the presents that you might get and the ice cream and the cake, because you’d get a pinch from my father, which really hurt, to grow an inch. After the pinch you got a swat for each year since your birth. I never liked that. Seemed weird. You’d have to spend most of the day trying not to get caught.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

When Edie was five, a new nurse came along called Addie. She was different from the earlier NURSES in that she was utterly loving and gentle. She was a pudding of a person, white

whiskers, buck teeth, a small skull, and a big, fat face. There was just not one mean thing about that woman—she was something out of a fairy tale, but she was incapable of maintaining any kind of authority. Edie was unbelievably cruel to her and kicked her, but she loved her very much.

Some of the games Edie and Suky played seemed a little sadistic at times. Edie turned Suky into a horse, herself into a wolf, and she chased Suky, whimpering and whinnying, out into the fields. That game terrified Suky and gave her nightmares. She even began to see wolves in the scrapbasket. Edie also made a whole series of animal heads to go on a broomstick, and she’d ride around on them. But the heads had to be perfect.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

When it came to real horses, Edie would always get the best-looking one. She could get anything she wanted. Spoiled. Even if I had the best-looking horse, it became

her

horse because she convinced everyone that I was too heavy for him and that he’d get tired under my weight. That was cool; it didn’t bother me.

We were on top of horses at fourteen months. They’d prop us up on them for a picture to be taken, and then you’d keep wanting a horse. Everybody rode, and you just started riding the first thing you could. The big game was Cowboys and Indians. One would be a cowboy and the other an Indian and we’d chase each other through the trees. Edie and Suky rode at night, through the moonlight. I didn’t ever go with them. I don’t know what they talked about. They’d get up really early and watch the sun come up—things like that.

I remember this picture of us being lined up on our horses. Weird trip. Bobby didn’t like it at all. Saucie thought it was strange. Pamela tried to play it super cool. Minty was just bashful, and Kate was smily. But Edie . . . she seemed French to me when this one was taken. The picture was for an article in

Life

magazine which never appeared, called The Working American” or something like that, and it was supposed to show how we worked the ranch with horses and eight children. Edie is on Zorillo, which means Skunk in certain derivations of the word in Spanish. Otherwise it means Little Fox. She really knew how to get it on. Look at her, man. Little French lady. Already her hands are in place; nobody else has their hands that way. She already has her little thing going.

SAPCIE SEDGWICK

I remember thinking how phony the

Life

pictures were—the family wasn’t united like that at all. The main thing

I resented was the image of everyone sitting together devotedly reading after dinner. We read after dinner only because nobody could

talk

about anything. It was a form imposed, like a cookie cutter, from outside.

There isn’t much in common between these cosmetic pictures and the old photos of the earlier Sedgwicks with their amusing, knobbly faces . . . they all looked like a bunch of Jerusalem artichokes. The “Sedgwick Nose” is large and curves downward like a beak. None of us got it, though my parents kept an eye on Minty. I told you my father thought I looked like a sausage when I was born. “Sausie” is what’s in the early photograph albums and on my christening pin. My father used to say, “Sauce, pauce, puddin’ and pie, kissed the boys and made them cry.” He also called me Puddin’. He had nice nicknames for us. Kate was Miss Rincus, Kate-a-rinks-Kate-a-rincus. Minty was Squints, Squinterino. Pamela was Pamelelagraph, Giraffe. Edie was Weedles, sometimes Weasel. At dinner he would carve, and he would say, “Well, what are you going to have, Miss Weedles?” He would sometimes refer to the whole lot of us as “monkeyshines.”

My parents also named animals very well. My mother had a mare named Lady Murasaki, and Flying Cloud was my father’s horse—so beautiful, a pale strawberry roan. Gazette was also my father’s horse, even though he was too heavy for her. She was a lovely dappled gray, small and slight and narrow in the chest, and my father was a big man and he had all this macho stuff on his saddle. He kept a rope, though he didn’t rope. His saddle must have weighed 50 or 60 pounds, and he weighed 180. He was so heavy for her that she would “cross feet” when she was tired in order to support his weight. She was the most beautiful, affectionate, intelligent creature . . . absolutely responsive. My father practically didn’t have to use the reins at all. He loved her very much, but he didn’t reduce the weight of his tack. It reminded me of the scenes where Vronsky breaks his mare’s back in

Anna Karenina.

My father looked terrific on a horse, but my mother was “with” her horse when she rode, though she didn’t look like much. She never braced like a cowboy; she rode forward as an English rider might who was sitting to the trot, so she jiggled a lot. But the cowboys said she was really the good rider. She had wonderful hands and a real feeling for her horse. The animals loved her very much. When we would go riding, the dogs would come tumbling after. Lord, there were the dogs. My parents had two Airedales named Gog and Mig. There was Queechy, an English bull terrier who was very fierce . . . a fiend . . . my father’s dog. When Edie was little, they had a St. Bernard named Pougachev for the leader of the people’s rebellion in the time of Catherine the Great. They had Great Danes—a dog named Woof who was half Great Dane and half greyhound.