Edie (8 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

CEREMONY IN GRACE CHURCH

Rev. Dr. Peabody Officiates—Bridal Party Passes Through a Lane of White and Green

There was a representative gathering of old New York families yesterday afternoon in Grace Church, Broadway and Tenth Street, for the marriage of Miss Alice de Forest, younger daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Henry W. de Forest of this city and Nethermuir, Cold Spring Harbor, L.I., to Francis Minturn Sedgwick, son of Henry Dwight Sedgwick, author, and the late Mrs. Sedgwick, who was a member of the Minturn family of this city. . . .

The Rev. Dr. Endicott Peabody, headmaster of Groton School, where the bridegroom prepared for college, performed the ceremony. He was assisted by the Rev. Dr. W. Russell Bowie, rector of Grace Church. There was a full choral service, the vested choir singing “Ancient of Days” as it made its way from the vestry room to the choir stalls. As the bride entered the church escorted by her father, the choir sang the Lohengrin wedding march. . . .

. . . At the chancel steps she was joined by the bridegroom and his brother, Robert Minturn Sedgwick, the best man. . . . She wore a princess costume of ivory colored satin, the skirt shorter in front and ending in a long train in the back. She wore two veils, one of old family lace over another of tulle edged with godet ruffles of tulle. The veils extended to the end of the long train and were arranged with a cap of lace caught across the back of the head with a narrow bandeau of tiny orange blossoms. Her bouquet was of lilies of the valley.

The costumes of the bridesmaids were of primrose yellow chiffon, that of the matron of honor being of a darker shade of yellow. All the attendants wore large picture hats of yellow straw trimmed with apple green moiré ribbon. Their bouquets were of pink and yellow Spring flowers and blue iris.

. . . Owing to the recent illness of the bride’s mother, there was no reception.

. . . Mr. Sedgwick and his bride after their wedding trip to California wI’ll live in Cambridge, Mass., while he continues his studies at the business school of Harvard.

. . . As the bride and bridegroom left the chancel Mendelssohn’s wedding march was played on the organ by Ernest Mitchell, organist of Grace Church, and as they left the church the chimes were rung. For the recessional the choir sang “Rejoice the Lord Is King.”

. . . During the service the choir sang “Oh Perfect Love.”

My parents had a great deal in common. They both liked being outdoors—riding, swimming, playing tennis. They shared a certain scorn for social phoniness. They adored dogs and horses. They were both talented artistically. And on the other hand they had a shadow side in common—each had lost an idolized elder brother. Both had implacable grieving mothers and must have lived with a terrible sense of jeopardy.

My mother must have seemed a strong, compassionate figure to my father, and her family offered the sense of security and power he was looking for. He was drawn, to my grandfather de Forest as a father figure—he was always looking for a powerful, rich, well-born person in the mainstream of things rather than a scholarly dreamer like his own father. My mother seemed to have everything—no wonder he fell in love with her. For her part she was painfully shy and must have felt secure marrying someone so dashing who would yet be totally dependent upon her and on her father. When my father proposed, she had no reservations about marrying him. My grandparents insisted on a medical opinion before giving their permission. But my mother’s commitment was—and remained—total.

MINTCRN SEDGWICK

The de Forests were crazy about Francis. I mean, so it appeared. Francis claimed he overheard Mr. de Forest saying, “I hope young Sedgwick wins the race.” Anyway, they were engaged. Francis came back from England and I met him at the dock. He looked the picture of health, but suddenly he said, “Gubby”—that’s what he called me—”you’ve got to pass my baggage out. I’ll collapse if I stand around here.” He was in trouble. He went around to various doctors who did him no good, and then he asked if I could get him into the Austen Biggs Center in Stockbridge.

JEAN STEIN

Dr. John Millet was assigned as Francis Sedgwick’s psychiatrist at Biggs. His father was a painter—Mark Twain had been his father’s best man. Mr. Sedgwick spent three months at Biggs under his care. He had a large private room with a chaise longue by the fireplace. The patients were called “guests.” Mr. Sedgwick’s bed was turned down by a maid, who left him a pitcher of milk by his bedside table.

Alice de Forest visited Francis Sedgwick regularly. It must have been very difficult for her. Dr. Biggs, the head of the Biggs Center, and Dr. Millet told them that Mr. Sedgwick was recovering from a

phase of manic-depressive psychosis. Dr. Millet suggested that Mr. Sedgwick rest for a few months and then have a quiet wedding and honeymoon.

MINTURN SEDGWICK

Mr. de Forest went to see Dr. Biggs and Dr. Millet, and the reports were not very encouraging. He telephoned me and said, “The next time you’re in New York I’d appreciate it if you’d come and call on me.” So I said I’d be delighted, and I saw the great man in his office. The first thing he said was: “We’re advised that Francis and Alice shouldn’t have any children.” Well, to me that meant: Don’t get married. But there was nothing I could do about it. The service was held in Grace Church in New York. Like most Groton boys, Francis was a tremendous admirer of the Rector, Mr. Peabody, and he had him at the wedding to perform the service. But Francis didn’t realize that under church protocol it’s the clergyman of the church who has to declare you man and wife. I was Francis’ best man; we met there early to run over the high points before the service. When he overheard the Rector say that the other fellow would make the final pronouncement, Francis told me in such a loud voice that the clergyman must have heard, “If I’d known

that,

we wouldn’t be married in this church!” There was never a moment when Francis didn’t want to have his way.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

I was the first child—born Alice on August 29, 1931, a little more than two years after my parents were married. I was nicknamed Saucie—short for sausage, which is what my father thought I looked like at birth. Edie was the seventh child. Between Edie and me, the children came along every two years or so—Bobby, Pamela, Minty, Jonathan, and Kate—and then the eighth, Suky, was born in 1945. Our lives as we grew up were divided between winters in Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island and summers at a house in Santa Barbara that my parents had bought on their honeymoon.

The year after their marriage my parents lived in Cambridge while my father attended classes at the Harvard Business School. He was bored by learning the nuts and bolts of business, and by 1930 the prospects for future tycoons must have been pretty dismal. Even brilliant businessmen like my grandfather de Forest were losing millions in the Depression. Also my father was having asthma attacks and other nervous symptoms, so his doctors advised him to develop his artistic side.

My parents moved to Long Island, where they spent winters first in a house called Airslie on my grandfather de Forest’s place, and eventually in a house of their own nearby. My father became a sculptor. I think he was ashamed not to be a banker like everyone else who took the Long Island Railroad into town, so he commuted into New York wearing a bowler hat and carrying an umbrella. He looked as if he

was going to spend the day at Number One Wall Street. Our butler, William Kennedy, would drive him to the train, and often he’d finish his breakfast in the car, his eggs on a plate in his lap, because he was always late. He’d go to classes at the National Academy of Fine Arts and then spend the day at his studio on East Fifty-seventh Street. His cousin Gifford Pinchot told me he went there once and discovered my father in a G-string strapped to a huge cross, staring at himself in a full-length mirror. He explained that he was doing a crucifixion scene and didn’t want to be bothered to pay a model.

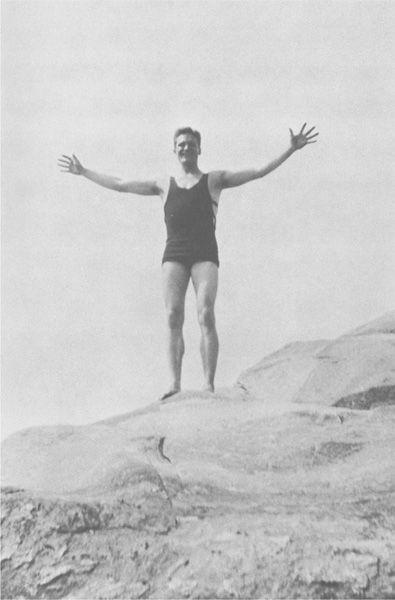

Typical of my father to see himself as a combination of Messiah, victim, and great male nude. Oh, he worked very hard on himself. It was an obsession with him to be strong and fit. At Cold Spring Harbor he rowed a single scull out on the pond, and he ran five miles in his little running shorts at night when he came home from New York. One of the major memories of my childhood is the punching bag and the sound of it being hit:

pocketa, tocketa, pocketa, tocketa.

He was scornful of people who were not physically fit. He told me once he would never vote for Adlai Stevenson, whom he used to see at the Francis Plimptons’, because “he looked like a woman—breasts and a flabby stomach—and besides he was bald.”

GEORGE PLIMPTON

I can remember very well when the Sedgwicks came to our house to play mixed doubles against my parents. Francis Sedgwick was a very romantic figure to my young eyes . . . close-cropped hair—it sort of shone like a beaver’s pelt—and his bare chest, of course. He never wore a tennis shirt. He drove over from Cold Spring Harbor in his convertible with the top down and his chest bare. He was very tan. I remember a sort of soldier’s stance and his walk, very cocky. He had a habit of slapping at the back of his calves with the edge of his racquet as he walked down the slope toward the tennis court. Very lively man. A smile that blazed out of that dark tan. There was always a lot of banter and jollity on the court. It was fun to watch the Sedgwicks play. They made everyone else around feel a little rumpled and dowdy. I envied the children their parents.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My father hadn’t really wanted to have children. My mother told me once that it used to break her heart that he just wasn’t interested in the little things she told him about us. She would say, “Aren’t they sweet?” and he wouldn’t respond. He didn’t want to be called Daddy; he wanted us to call him Fuzzy, the name my mother had given her own father.

MINTURN SEDGWICK

I described my brother Francis to a friend of mine after he’d had his eighth child, and how surprised I was, considering the increasing difficulties Alice had in childbirth, and she said, “I’ll bet he had those children just to show he could have more than anyone else.” It might well have been. I know he was pleased that no one else in his Harvard class had produced eight children, or anything close. After the eighth, Susanna, was born, I sent him one of those canned telegram messages, “Good work, keep it up”—a slightly sardonic message, considering the circumstances. He never acknowledged it.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

little children get sick a lot, of course, and by the time there were three or four of us, colds and measles and all those things would just go bouncing from one of us to another. There were always doctors and nurses around. Minty, I remember, had to wear a horrible sort of wire helmet on his head to flatten his ears. He came down with scarlet fever when he was quite small and had to be watched for a heart condition. Bobby used to rock in his bed and bang his head. Twice he ran through the glass of the French doors leading to the terrace of our house in Cold Spring Harbor, and cut his wrists horribly. The second time, we were all being driven into New York by Grandpa de Forest’s old steward, Dancer, to see the Lionel train exhibit. Bobby was dressed up in his little gray flannel suit with short pants and no lapels, and the blood began to seep through his sleeves. He hadn’t said a word.

My mother took care of us on the nurse’s day off and gave us baths. She would take Bobby into her bed and comfort him when he had nightmares. Nurses were let go if they were unable to cope with disciplining us. The only time I ever saw my mother cry then was when she had to discharge a nurse. It upset her terribly.

Our house in Cold Spring Harbor was dark and gloomy, although it had a rather pretty situation on a pond. My parents built a long, high cinderblock wall to shut out the noise of the road, which gave the place an ominous look. I suppose we lived there to be near my grandparents, although there was a lot of tension under the surface between my parents and my grandmother. My father told me that when my mother’s brother Charlie died—he died of typhoid fever in Rome right after my parents married—Grandma had actually said to my mother, “Oh, why couldn’t it have been you?” I have no idea if that’s true or not. You don’t know what people wI’ll say under stress.

Francis Sedgwick