Emotional Design (27 page)

Authors: Donald A. Norman

The problem is that these simple physiological measures are indirect measures of affect. Each is affected by numerous things, not just by affect or emotion. As a result, although these measures are used in many clinical and applied settings, they must be interpreted with care. Thus, consider the workings of the so-called lie detector. A lie detector is, if anything, an emotion detector. The method is technically called “polygraph testing” because it works by simultaneously recording

and graphing multiple physiological measures such as heart rate, breathing rate, and skin conductance. A lie detector does not detect falsehoods; it detects a person's affective response to a series of questions being asked by the examiner, where some of the answers are assumed to be truthful (and thus show low affective responses) and some deceitful (and thus show high affective arousal). It is easy to see why lie detectors are so controversial. Innocent people might have large emotional responses to critical questions while guilty people might show no response to the same questions.

and graphing multiple physiological measures such as heart rate, breathing rate, and skin conductance. A lie detector does not detect falsehoods; it detects a person's affective response to a series of questions being asked by the examiner, where some of the answers are assumed to be truthful (and thus show low affective responses) and some deceitful (and thus show high affective arousal). It is easy to see why lie detectors are so controversial. Innocent people might have large emotional responses to critical questions while guilty people might show no response to the same questions.

Skilled operators of lie detectors try to compensate for these difficulties by the use of control questions to calibrate a person's responses. For example, by asking a question to which they expect a lie in response, but that is not relevant to the issue at hand, they can see what a lie response looks like in the person being tested. This is done by interviewing the suspect and then developing a series of questions designed to ferret out normal deviant behavior, behavior in which the examiner has no interest, but where the suspect is likely to lie. One question commonly used in the United States is “Did you ever steal something when you were a teenager?”

Because lie detectors record underlying physiological states associated with emotions rather than with lies, they are not very reliable, yielding both misses (when a lie is not detected because it produces no emotional response) and false alarms (when the nervous suspect produces emotional responses even though he or she is not guilty). Skilled operators of these machines are aware of the pitfalls, and some use the lie detector test as a means of eliciting a confession: people who truly believe the lie detector can “read minds” might confess just because of their fear of the test. I have spoken to skilled operators who readily agree to the critique I just provided, but are proud of their record of eliciting voluntary confessions. But even innocent people have sometimes confessed to crimes they did not commit, strange as this might seem. The record of accuracy is flawed enough that the National Research Council of the United States National Academies performed a lengthy, thorough study and

concluded that polygraph testing is too flawed for security screening and legal use.

concluded that polygraph testing is too flawed for security screening and legal use.

Â

Â

SUPPOSE WE could detect a person's emotional state, then what? How should we respond? This is a major, unsolved problem. Consider the classroom situation. If a student is frustrated, should we try to remove the frustration, or is the frustration a necessary part of learning? If an automobile driver is tense and stressed, what is the appropriate response?

The proper response to an emotion clearly depends upon the situation. If a student is frustrated because the information provided is not clear or intelligible, then knowing about the frustration is important to the instructor, who presumably can correct the problem through further explanation. (In my experience, however, this often fails, because an instructor who causes such frustration in the first place is usually poorly equipped to understand how to remedy the problem.)

If the frustration is due to the complexity of the problem, then the proper response of a teacher might be to do nothing. It is normal and proper for students to become frustrated when attempting to solve problems slightly beyond their ability, or to do something that has never been done before. In fact, if students aren't occasionally frustrated, it probably is a bad thingâit means they aren't taking enough risks, they aren't pushing themselves sufficiently.

Still, it probably is good to reassure frustrated students, to explain that some amount of frustration is appropriate and even necessary. This is a good kind of frustration that leads to improvement and learning. If it goes on too long, however, the frustration can lead students to give up, to decide that the problem is above their ability. Here is where it is necessary to offer advice, tutorial explanations, or other guidance.

What of frustrations shown by students that have nothing to do with the class, that might be the result of some personal experience, outside the classroom? Here it isn't clear what to do. The instructor,

whether person or machine, is not apt to be a good therapist. Expressing sympathy might or might not be the best or most appropriate response.

whether person or machine, is not apt to be a good therapist. Expressing sympathy might or might not be the best or most appropriate response.

Machines that can sense emotions are an emerging new frontier of research, one that raises as many questions as it addresses, both in how machines might detect emotions and in how to determine the most appropriate way of responding. Note that while we struggle to determine how to make machines respond appropriately to signs of emotions, people aren't particularly good at it either. Many people have great difficulty responding appropriately to others who are experiencing emotional distress: sometimes their attempts to be helpful make the problem worse. And many are surprisingly insensitive to the emotional states of others, even people whom they know well. It is natural for people under emotional strain to try to hide the fact, and most people are not experts in detecting emotional signs.

Still, this is an important research area. Even if we are never able to develop machines that can respond completely appropriately, the research should inform us both about human emotion and also about human-machine interaction.

Machines That Induce Emotion in PeopleIt is surprisingly easy to get people to have an intense emotional experience with even the simplest of computer systems. Perhaps the earliest such experience was with Eliza, a computer program developed by the MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum. Eliza was a simple program that worked by following a small number of conversational scripts that had been prepared in advance by the programmer (originally, this was Weizenbaum). By following these scripts, Eliza could interact with a person on whatever subject the script had prepared it for. Here is an example. When you started the program, it would greet you by saying: “Hello. I am ELIZA. How can I help you?” If you

responded by typing: “I am concerned about the increasing level of violence in the world,” Eliza would respond: “How long have you been concerned about the increasing level of violence in the world?” That's a relevant question, so a natural reply would be something like, “Just the last few months,” to which Eliza would respond, “Please go on.”

responded by typing: “I am concerned about the increasing level of violence in the world,” Eliza would respond: “How long have you been concerned about the increasing level of violence in the world?” That's a relevant question, so a natural reply would be something like, “Just the last few months,” to which Eliza would respond, “Please go on.”

You can see how you might get captured by the conversation: your concerns received sympathetic responses. But Eliza has no understanding of language. It simply finds patterns and responds appropriately (saying “Please go on” when it doesn't recognize the pattern). Thus, it is easy to fool Eliza by typing: “I am concerned about abc, def, and for that matter, ghi,” to which Eliza would dutifully reply: “How long have you been concerned about abc, def, and for that matter, ghi?”

Eliza simply recognizes the phrase “I am concerned about X” and replies, “How long have you been concerned about X?” with absolutely no understanding of the words.

Because most people took Eliza seriously, they did not try to trick it. Instead, they took each reply seriously, pondering their hidden meanings. As a result, they would sometimes discover themselves in deep, philosophical debate or, in the most popular version of Eliza that was scripted to act like a psychotherapist, they would find themselves discussing their most intimate secrets.

In the mid-1960s, one of my long-term friends and research collaborators, Daniel Bobrow, was a research scientist at BBN, a Cambridge, Massachusetts company doing research in artificial intelligence, computer networks, and acoustics. Bobrow told me that a programmer, having worked hard to get Eliza working on a BBN computer, finally finished about 5:00 A.M. Saturday morning and then went home, leaving the program running on the computer. (In those daysâthis was 1966âpersonal computers were unheard of, and only advanced companies, such as BBN, even had computers for its employees to use, which is one reason programmers had to work at night to get computer time.)

The vice president of Bobrow's division came in later that Saturday morning to demonstrate the computer to some customers. Seeing that

the computer was running, he assumed that Bobrow was using it from home, and, according to Bobrow, “decided to use the âobvious' communication link I must have left going” to chat with him. So the VP typed some questions for Bobrow. But Bobrow was at home, asleep, and what ensued was actually taking place between Eliza and the VP, who assumed these responses came from Bobrow:

the computer was running, he assumed that Bobrow was using it from home, and, according to Bobrow, “decided to use the âobvious' communication link I must have left going” to chat with him. So the VP typed some questions for Bobrow. But Bobrow was at home, asleep, and what ensued was actually taking place between Eliza and the VP, who assumed these responses came from Bobrow:

VP:

Do you think that I can use the computer this morning?

Do you think that I can use the computer this morning?

Eliza:

Why do you ask?

Why do you ask?

VP:

I might be able to make some additional Telcom sales.

I might be able to make some additional Telcom sales.

Eliza:

Why aren't you so sure?

Why aren't you so sure?

VP:

My prospective customers have never seen a demonstration of the system.

My prospective customers have never seen a demonstration of the system.

Eliza:

Does this mean very much to you?

Does this mean very much to you?

VP:

Of course it does.

Of course it does.

Eliza:

You seem very positive about that.

You seem very positive about that.

VP:

This is ridiculous.

This is ridiculous.

Eliza:

What do you mean, this is ridiculous?

What do you mean, this is ridiculous?

VP:

Is there any reason why I can't use the computer now?

Is there any reason why I can't use the computer now?

Eliza:

Tell me more about your prospective customers.

Tell me more about your prospective customers.

VP:

Please dial me up on 491-1850

Please dial me up on 491-1850

In those days, computers were not very powerful, and the only way that the Eliza program could tell when a person had finished a sentence was by noticing a period. Up to that last line, the VP had finished each line with a period, but this time he neglected it. As a result, the computer kept waiting for more typing and, therefore, didn't answer. According to Bobrow, “This so infuriated the VP, who thought I was playing games with him, that he called me up, woke me from a deep sleep, and said: âWhy are you being so snotty to me?' âWhat do you mean I am being snotty to you?,' I answered.” Then, Bobrow told me, “The VP angrily read me the dialog that âwe ' had been having, and couldn't get any response but laughter from me. It took a while to convince him it really was a computer.”

As Bobrow told me when I discussed this interaction with him, “You can see he cared a lot about the answers to his questions, and what he thought were my remarks had an emotional effect on him.” We are extremely trusting, which makes us very easy to fool, and very angry when we think we aren't being taken seriously.

The reason Eliza had such a powerful impact is related to the discussions in chapter 5 on the human tendency to believe that any intelligent-seeming interaction must be due to a human or, at least, an intelligent presence: anthropomorphism. Moreover, because we are trusting, we tend to take these interactions seriously. Eliza was written a long time ago, but its creator, Joseph Weizenbaum, was horrified by the seriousness with which his simple system was taken by so many people who interacted with it. His concerns led him to write

Computer Power and Human Reason,

in which he argued most cogently that these shallow interactions were detrimental to human society.

Computer Power and Human Reason,

in which he argued most cogently that these shallow interactions were detrimental to human society.

We have come a long way since Eliza was written. Computers of today are thousands of times more powerful than they were in the 1960s and, more importantly, our knowledge of human behavior and psychology has improved dramatically. As a result, today we can write programs and build machines that, unlike Eliza, have some true understanding and can exhibit true emotions. However, this doesn't mean that we have escaped from Weizenbaum's concerns. Consider Kismet.

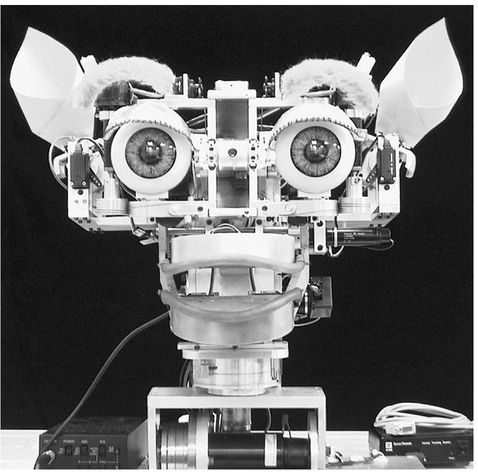

Kismet, whose photograph is shown in

figure 6.6

, was developed by a team of researchers at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and reported upon in detail in Cynthia Breazeal's

Designing Sociable Robots

.

figure 6.6

, was developed by a team of researchers at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and reported upon in detail in Cynthia Breazeal's

Designing Sociable Robots

.

Recall that the underlying emotions of speech can be detected without any language understanding. Angry, scolding, pleading, consoling, grateful, and praising voices all have distinctive pitch and loudness contours. We can tell which of these states someone is in even if they are speaking in a foreign language. Our pets can often detect our moods through both our body language and the emotional patterns within our voices.

Kismet uses these cues to detect the emotional state of the person

with whom it is interacting. Kismet has video cameras for eyes and a microphone with which to listen. Kismet has a sophisticated structure for interpreting, evaluating, and responding to the worldâshown in

figure 6.7

âthat combines perception, emotion, and attention to control behavior. Walk up to Kismet, and it turns to face you, looking you straight in the eyes. But if you just stand there and do nothing else, Kismet gets bored and looks around. If you do speak, it is sensitive to the emotional tone of the voice, reacting with interest and pleasure to encouraging, rewarding praise and with shame and sorrow to scolding. Kismet's emotional space is quite rich, and it can move its head, neck, eyes, ears, and mouth to express emotions. Make it sad, and its ears droop. Make it excited and it perks up. When unhappy, the head droops, ears sag, mouth turns down.

with whom it is interacting. Kismet has video cameras for eyes and a microphone with which to listen. Kismet has a sophisticated structure for interpreting, evaluating, and responding to the worldâshown in

figure 6.7

âthat combines perception, emotion, and attention to control behavior. Walk up to Kismet, and it turns to face you, looking you straight in the eyes. But if you just stand there and do nothing else, Kismet gets bored and looks around. If you do speak, it is sensitive to the emotional tone of the voice, reacting with interest and pleasure to encouraging, rewarding praise and with shame and sorrow to scolding. Kismet's emotional space is quite rich, and it can move its head, neck, eyes, ears, and mouth to express emotions. Make it sad, and its ears droop. Make it excited and it perks up. When unhappy, the head droops, ears sag, mouth turns down.

Other books

Bodies of Light by Lisabet Sarai

Lucky: The Irish MC by West, Heather

Conventions of War by Walter Jon Williams

Westward Holiday by Linda Bridey

Jericho by George Fetherling

The Donor by Nikki Rae

The Curse of the King by Peter Lerangis

His Marriage Trap by Sheena Morrish

Believing by Wendy Corsi Staub

Weekend Surrender by Lori King