Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (24 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

On Your Toes

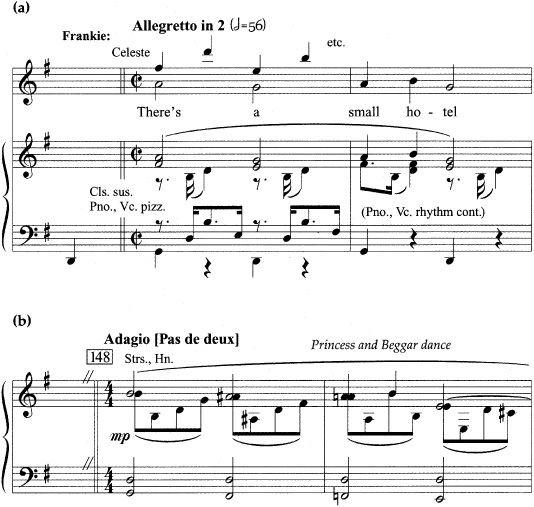

In his notes to the 1983 revival, recording conductor John Mauceri writes tantalizingly of musical organicism in

On Your Toes

: “The score is full of musical ‘cross-references’” like the theme of the pas de deux in ‘Princesse Zenobia’ having the same rhythmic structure as ‘There’s a Small Hotel’ [

Example 5.4

]. The great composers of the American musical theater were not merely tunesmiths but composers of songs, ensembles and occasionally larger structures, like Schumann, Mendelssohn and Schubert a century before them.”

33

Example 5.4.

“There’s a Small Hotel” and “La Princesse Zenobia” Ballet

(a) “There’s a Small Hotel,” original song

(b) transformation in “La Princesse Zenobia” ballet

Mauceri’s message is that great works of theatrical art such as

On Your Toes

possess unity and structural integrity not usually associated with musical comedy—and, by implication, that large works are more worthy of praise than “mere” tunes. And certainly “There’s a Small Hotel” and “Princesse Zenobia” have much in common melodically as well as rhythmically. Since this song has previously served as the love duet between Junior and Frankie, it is dramatically convincing when Rodgers uses a transformed version of this song for a

pas de deux

(the balletic equivalent of a love song) that depicts the love between the Beggar (Morrosine) and the Princesse (Vera).

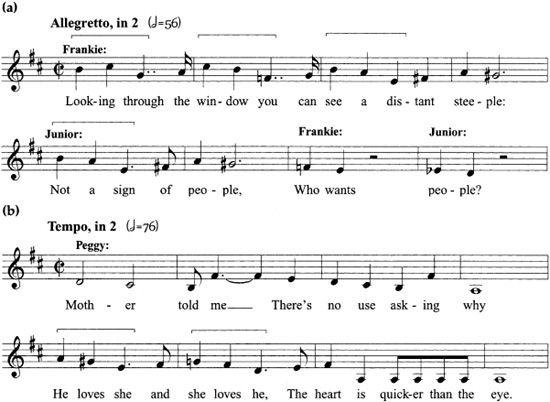

Additional examples of organicism include the rhythmic and sometimes melodic connections between the release or B section of “There’s a Small Hotel” (which, unlike “It’s Got to Be Love,” displays the more usual A-A-B-A thirty-two-bar form with each letter representing eight measures) and the first phrase of “The Heart Is Quicker Than the Eye” (also A-A-B-A) shown in

Example 5.5

. Mauceri might have noted that Rodgers reuses the dotted rhythmic accompaniment of “Small Hotel” to accompany the main theme of “Slaughter” for the jazzy duet between Junior (who knows the tune pretty well by now) and the stripper Vera. He might also have mentioned that the accompaniment of the second half of the verse, beginning with the words “see … looks gold to me” of “It’s Got to Be Love” also anticipates the rhythmic accompaniment throughout “There’s a Small Hotel” and the

pas de deux

between Junior and Vera in “Slaughter.” Nevertheless, in contrast to the vast network of connections previously observed in

Show Boat

and

Porgy and Bess

, examples of organicism in

On Your Toes

are comparatively rare. More important, Rodgers, although he does employ the musical device of foreshadowing for dramatic purposes, especially of his second ballet, “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue,” for the most part does not exploit the dramatic potential of his musical connections as he would later with Hammerstein.

34

Example 5.5.

“There’s a Small Hotel” and “The Heart Is Quicker Than the Eye”

(a) “There’s a Small Hotel” (B section, or release)

(b) “The Heart is Quicker Than the Eye” (opening of chorus)

Musical comedies before

Oklahoma!

and

Carousel

are almost invariably criticized for their awkward transitions from dialogue into music. The segue into “There’s a Small Hotel” (act I, scene 6), a big hit song in the original production, provides a representative example by its absence of any references in the dialogue that lead plausibly, much less naturally or inevitably, to the song. In his 1983 revision Abbott tries to remedy this:

FRANKIE

: Oh, Junior, I wish we were far away from all this.

JUNIOR

: Yes, so do I. With no complications in our lives.

FRANKIE

: Yes.

JUNIOR

(

Goes to her

): Oh yes … very far away … Paris maybe.

35

If the revised dialogue constitutes an improvement over the Central Park setting of the 1936 original, where “There’s a Small Hotel” almost literally comes out of nowhere, it does not fully solve the problem of how a librettist or an imaginative director can successfully introduce a song like “There’s a Small Hotel.” “It’s Got to Be Love” may subtly reflect Frankie’s disguised obsession with veiled descending melodic sequences, but not even with all the wisdom of his advancing years could a genius such as Abbott make these songs grow seamlessly out of the dramatic action. But perhaps the point is that if we think of the song and its performance

as the show

rather than an interruption that “stops” the show, so-called integrated dramatic solutions are less necessary?

Several days before

Pal Joey

’s 1952 revival, Rodgers wrote in the

New York Times

that “Nobody like Joey had ever been on the musical comedy stage before.”

36

In his autobiography Rodgers concluded that of the twenty-five musicals he wrote with Hart,

Pal Joey

remained his favorite, an opinion also shared by his lyricist.

37

Porter’s

Anything Goes

may be more frequently revived. Several Rodgers and Hart shows, including

A Connecticut Yankee

(1927) in its revised 1943 version,

Babes in Arms

(1937), and

The Boys from Syracuse

(1938) can boast as many or even more hits. The scintillating

On Your Toes

can claim two full-length ballets and an organic unity unusual in musical comedies. Despite all this, only

Pal Joey

has proven that it can be successfully revived without substantial changes in its book or reordering of its songs.

The genesis of the musical

Pal Joey

, based on John O’Hara’s collection of stories in epistolary form, can be traced to 1938 when a single O’Hara short story, “Pal Joey,” was published in the

New Yorker

. By early 1940, shortly after Rodgers had received O’Hara’s letter suggesting a collaboration on a musical based on his collection, an additional eleven Joey stories (out of a total of thirteen) had appeared.

38

A normal five-week rehearsal schedule began on November 11 and tryouts took place in Philadelphia between December 16 and 22. Directed by Abbott and starring Gene Kelly as Joey and Vivienne Segal as Vera Simpson, the musical made its Broadway premiere at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on Christmas Day and closed 374 performances later at the St. James Theatre on November 29, 1941.

39

In his now-infamous review

New York Times

theater critic Brooks Atkinson found

Pal Joey

“entertaining” but “odious.” Referring to the disturbing subject matter, including adultery, sexual exploitation, blackmail, the somewhat unwholesome moral character of the principals, and a realistic and unflattering depiction of the seamy side of Chicago night life, Atkinson concluded his review with the question, “Although it is expertly done, can you draw sweet water from a foul well?”

40

Other critics greeted

Pal Joey

as a major “advance” in the form. Burns Mantle, for example, compared it favorably with the legitimate plays of the season and expressed his delight “that there are signs of new life in the musicals.”

41

And in

Musical Stages

Rodgers proudly quotes Wolcott Gibbs’s

New Yorker

review as an antidote to Atkinson: “I am not optimistic by nature but it seems to me just possible that the idea of equipping a song-and-dance production with a few living, three-dimensional figures, talking and behaving like human beings, may no longer strike the boys in the business as merely fantastic.”

42

Some reviewers noted weaknesses in the second act, but most praised O’Hara for

producing a fine book. John Mason Brown described the work as “novel and imaginative.”

43

Sidney B. Whipple lauded the “rich characterizations” and concluded that it was “the first musical comedy book in a long time that has been worth the bother.”

44

Pal Joey

appeared several years before the era of cast recordings, but in September 1950, ten years after its Broadway stage debut, a successful recording was issued with Vivienne Segal, the original Vera Simpson, and with Harold Lang as a new Joey. The recording generated considerable interest in the work and soon led to a revival on January 3, 1952, a sequence of events that foreshadowed the trajectories of several Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals of the 1970s and 1980s that were introduced as record albums and later evolved into stage productions. The 1952

Pal Joey

became the second major revival (after Cheryl Crawford’s 1942 revival of

Porgy and Bess

) to surpass its original run, and at 542 performances remains the longest running production of any Rodgers and Hart musical, original or revival. Even Atkinson, while not exactly admitting that he had erred in his 1940 assessment, lavishly praised the work as well as the production in 1952, including “the terseness of the writing, the liveliness and versatility of the score, and the easy perfection of the lyrics.”

45

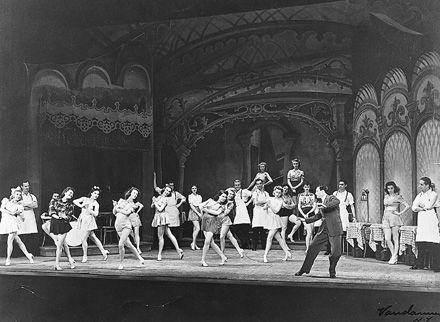

Pal Joey

. Gene Kelly in right foreground (1940). Photograph: Vandamm Studio. Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection.

After two successful revivals at the New York City Center in 1961 and 1963 (both with Bob Fosse in the title role), the artistic and commercial failure of a 1976 revival at New York City’s Circle in the Square—abandoned by New York City Ballet star Edward Villella shortly before opening night—would not cause

Pal Joey

to lose its place as a classic American musical, a place firmly established by the 1952 revival. As another sign of its artistic stature

Pal Joey

became the earliest musical to gain admittance in Lehman Engel’s select list of fifteen canonic musicals.

46

For Engel,

Pal Joey

inaugurated a Golden Age of the American musical.

47

in 1940 and 1952

Compared to the liberties taken with the 1962

Anything Goes

and the 1954

On Your Toes

, the 1952

Pal Joey

revival followed its original book and song content and order tenaciously. Nevertheless, some of what audiences heard and saw in 1952 departs from the original Broadway production. For example, in the 1952 revival, “Do It the Hard Way” is placed outside of its original dramatic context (act II, scene 4), when it is sung by Joey to Vera in their apartment; in 1940 this song is presented as a duet between Gladys and Ludlow Lowell in Chez Joey one scene earlier.

48

The 1952 lyrics also depart in several notable ways from O’Hara’s 1940 typescript.

49

In 1940 Hart concluded the chorus of “That Terrific Rainbow” (act I, scene 3) with the following quatrain: “Though we’re in those

GRAY

clouds / Some day you’ll see / That terrific

RAINBOW

/ Over you and me” (preserved on the pre-revival recording); for the 1952 revival someone (presumably not Hart) replaced two lines of this lyric with one that is grammatically incorrect, perhaps to emphasize the amateurish nature of the song. Thus “Some day you’ll spy” now rhymes with “Over you and I” (Hart rhymed “someday you’ll see” with “over you and me”). This alteration was adopted in the 1962 vocal score published by Chappell & Co.